1. Introduction

Pediatric long bone fractures (LBF) are frequent and have formerly been treated conservatively with several kinds of castings, with satisfactory outcomes. However, in certain instances, opting for the appropriate surgical procedure is crucial for achieving optimal results. Children’s activities become less constrained, and their tolerance for extended casting decreases as they grow bigger and older. Therefore, flexible nail fixation has become a popular technique for stabilizing pediatric LBF due to its advantages, such as minimal invasiveness, early mobilization, and reduced risk of growth plate injury.1,2

Flexible intramedullary nailing (FIN) provides many significant advantages for treating pediatric LBF that do not heal with closed reduction and casting. It is stable and adaptable as an internal splint, allowing for compression and micromotion at the fracture site, the ideal location for callus formation.3 The closed reduction technique using TENs preserves the fracture hematoma’s and periosteum’s integrity, allowing for better and quicker fracture healing.4 This technique enables early weight bearing and resumption of activities,5 which has led to its popularity and global adoption for pediatric LBF.6

The study at a Samtah General Hospital located in the Samtah district, southwest part of Saudi Arabia, aimed to analyze the functional outcomes of pediatric LBF treated with titanium elastic nails (TENs).

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Ethical considerations

The current research involved human participants and was carried out per the ethical guidelines specified in the Declaration of Helsinki. The research conducted in this study received ethical approval from the Jazan Health Ethics Committee, with the assigned approval number 2367. Before participating in the research, all individuals had to provide informed consent. After providing comprehensive information on the objective, methods, and potential risks and benefits of participation, written consent was obtained from each participant. The confidentiality and anonymity of participants’ replies were guaranteed, and precautions were used to protect the privacy of personal data throughout the study.

2.2. Study design

This study conducted a retrospective analysis of patient records to identify pediatric LBF cases (femur, tibia, and radius/ulna) treated with TENs fixation from January 2021 to December 2023. The data regarding patient demographics, mechanism of injury, fracture type, duration of hospital stay, surgical details (such as nail size, surgical and anesthetic technique), and time to achieve radiologic union were extracted.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All pediatric LBF, either closed or open (Grade I or II), treated with TENs during the mentioned period were included. Fractures classified as unstable in length, grade III open fractures, and those with underlying metabolic bone diseases were excluded from the study.

2.4. Surgical procedure

2.4.1. Preoperative measures

Preoperative radiographs were reviewed, and the marrow canal diameter was measured. The nail sizes were then calculated using Flynn et al.'s formula (diameter of nail=width of narrowest point of the medullary canal on Antero-Posterior and Lateral view X 0.4 mm). The fixations were either performed under general anesthesia in most cases or spinal anesthesia in patients older than 14 years with fractures in the lower limbs.

2.4.2. Fractures fixation techniques

All patients were supine on a radiolucent table with the image intensifier on the opposite side of the fracture. The involved upper limb was extended on a radiolucent arm board in the forearm while the image intensifier was positioned perpendicular to the forearm. The preferred technique was either to use the lateral entry point proximal to the radial styloid or the dorsal entry point near the Lister tubercle to fix the radius fracture, and the lateral approach in the proximal ulna metaphysis was used to fix the ulna fracture. In the femur, the retrograde technique using both the lateral and medial aspects of the distal femur at a point approximately 2.5-3 cm above the distal femoral physis was preferred. In contrast, an antegrade technique using both medial and lateral entry points away from the proximal physis was used in the tibia. In 2 older patients aged 9 and 15 years, a traction table was used to achieve partial reduction for femur fractures. The decision to use the traction table was made at the discretion of the primary surgeon.

2.4.3. Nail insertion technique

The nail was pre-bent to approximately 30⁰, aiming for the curve’s apex to be at the fracture site. An image intensifier was used to determine the appropriate bending point at the fracture site. In the case of a forearm fracture, only one nail was used for each bone. However, two nails of similar size were used for fractures in the femur and tibia. A closed reduction technique was preferred as best possible, but a tiny incision was made to enable a mini-open reduction technique if a closed reduction technique could not be used for any fracture.

2.4.4. Postoperative measures

All patients received intravenous Cefazolin (Cefazolin, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY) tailored to their body weight, administered after induction of anesthesia, and antibiotic prophylaxis was continued for 2 to 3 doses within the next 24-hour period based on the hospital protocol. In some cases, supplementary cast support was used for 2-3 weeks before allowing weight-bearing and free movement.

2.5. Follow-up and functional outcome evaluation

Follow-up was performed for varying periods, with radiographic control of the fractures until radiologic union was achieved and the time to radiologic union was recorded. This marked the end of follow-up for the patients. The Flynn et al. scoring system was used for the outcome measures. This outcome score evaluates four clinical parameters, namely, limb length inequality, degree of malalignment, absence or presence of pain, and complications, which are subsequently used to grade the outcome as excellent, satisfactory, or poor results, Table S1.7

3. Results

Only 26 patient records were included for analysis after screening the data, with a significant male preponderance, 4 females (15.4%) and 22 males (84.6%). Regarding age group, most were in 6-10 years, accounting for 19 patients (73.1%), five patients (19.2%) were in 11-15 years, and only two patients (7.7%) were >15 years, as depicted in Table 1. The average age was 9.6±2.8 (6-16 years).

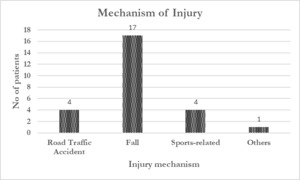

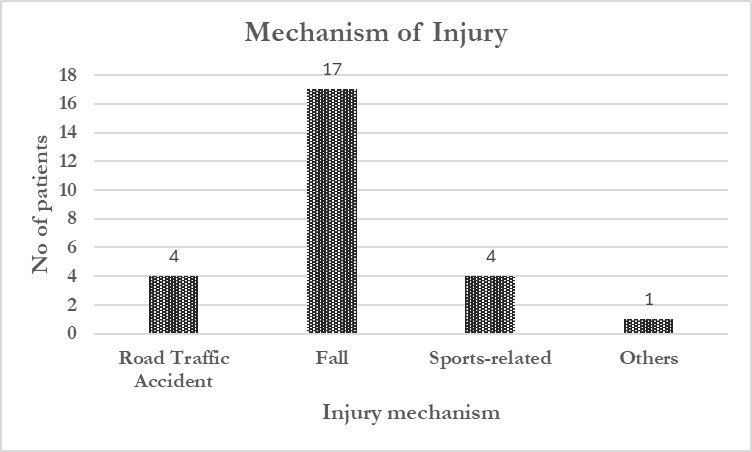

Self-fall was the most common cause of injury, accounting for 17 cases (65.4%). Road traffic injury and sports-related accidents accounted for 4 cases each (15.4%), and a single case (3.8%) was due to a home accident in which the child’s forearm was caught in a running washing machine, resulting in radius/ulna fractures, depicted in Figure 1.

Radius and ulna fractures of the forearm accounted for the highest number of cases (n=12, 46.2%), followed by the femur (n=8, 30.8%), tibia (n=5, 19.2%), and isolated ulna fracture (n=1, 3.8%). Fourteen patients (53.8%) had right-sided fractures, and 12 patients (46.2%) had left-sided fractures. Transverse was the most common fracture pattern, seen in 19 patients (73.1%), followed by oblique fractures in 6 patients (23.1%), with a single case of spiral fracture in the femur (3.8%). Proximal third location fractures account for 4 cases (15.4%), middle third for 17 cases (65.4%), and distal third for 5 cases (19.2%), shown in Table 2.

The open fractures represented three patients (11.5%); two presented with grade I open fracture, and one presented with grade II open fracture on the radial side of the fractures. All open fractures involved the forearm. The remaining 23 fractures (88.5%) were all closed, as described in Table 3.

Time to surgery was defined as the time from admission to fracture fixation. The average time to surgery was 2.9±1.9 (1-8 days), while the hospital stay duration was defined as the time elapsed between admitting the patients and final discharge. This study’s average hospital stay duration was 4.9±2.3 (2-12 days). Most patients were admitted for < 7 days (22 cases, 84.6%), while only four patients (15.4%) were admitted for >7 days. The average follow-up period was 6.5±3.3 (2-14 months). All patients were followed till radiographic union was achieved.

The time to achieve radiological union was defined as the time taken in weeks for bridging callus formation in three out of four cortices on both anteroposterior and lateral views of the radiographs. In 6-16 weeks, the average time to radiologic union was 11.5±2.9 weeks. Most patients (n=19, 73.1%) achieved union within 12 weeks, and the remaining patients (n=7, 26.9%) achieved union after 12 weeks, as shown in Figure 2.

In this study, the outcome was excellent in 19 patients (53.8%) and satisfactory in the remaining seven patients (46.2%), as shown in Table S2. Minor complications were recorded in 7 patients. These included skin irritation due to nail prominence at the entry point (5 patients), tolerable until nail removal, and superficial surgical site infection (2 patients), treated with antibiotics only, depicted in Figure S1. Figures S2-S4 show plain radiographs of some of the cases managed.

4. Discussion

The Nancy group in France popularised using TEN to fix pediatric LBF in the early 1980s.8 Since then, a high success rate of this technique has been reported in multiple studies.

The predominant mechanism of injury in this study was self-fall in 17 patients (65.4%), with road traffic injury and sports-related accidents being the mechanism in 4 patients each (15.4%). These results contradict the findings of the study by Tabish et al., in which motor vehicle accidents were the predominant mechanism of injury (68.9%), followed by falls from height (24.4%) and sports-related activities (6.7%), out of a total of 45 cases.9 Furthermore, this study also noted a rare mechanism, with a single case of a home accident (3.8%) in which the child’s forearm was caught in a running washing machine, resulting in radius/ulna fractures.

In terms of bone involvement, radius and ulna fractures accounted for the highest number with 12 patients (46.2%), followed by the femur in 8 patients (30.8%), the tibia in 5 patients (19.2%), and there was a single case (3.8%) of isolated ulnar fracture. In this study, right-sided fractures were more than left-sided fractures, accounting for 14 patients (53.8%) and 12 patients (46.2%), respectively. These findings aligned with the study by Gavaskar et al., which reported 18 patients (60%) with right-sided fractures and 12 patients (40%) with left-sided fractures. Regarding fracture location, it was evaluated that middle third fractures were the most common (n=17, 65.4%), followed by distal third fractures (n=5, 19.2%) and proximal third fractures (n=4, 15.4%). These results are also aligned with the findings of the study by Gavaskar et al., in which middle-third fractures were reported in 23 cases (77%), distal-third fractures in 4 cases (13%), and the proximal third of the diaphysis was involved in 3 cases (10%). Furthermore, the most common fracture pattern reported in this study was transverse, seen in 19 patients (73.1%), followed by oblique fractures in 6 patients (23.1%) and a single patient with a spiral fracture of the femur (3.8%). These findings are similar to Gavaskar et al., who reported a transverse pattern in 17 patients (50%), followed by short oblique in 7 patients (24%), spiral fracture in 6 patients (20%), and segmental and comminuted fracture in 1 patient (3%).10

According to this study, the average duration of hospital stay was 4.9±2.3 (2-12 days). Most patients were admitted for < 7 days in 22 cases (84.6%), while only four patients (15.4%) were admitted for >7 days. These findings aligned with the results of the prospective study conducted by Raut et al., on 30 patients reported that 25 patients (83.3%) had ≤ 7 days of hospital stay, and the remaining five patients (16.7%) stayed for 7-14 days.11 In this study, more extended hospital stays were often due to incidental findings of anemia or electrolyte imbalance requiring pediatrician review before surgery.

The average follow-up period in this study was 6.5±3.3 (2-14 months). In this study, the mean time to radiologic union in weeks was 11.5±2.9 (6-16 weeks). The average union time for forearm and tibia fractures was 11 weeks, and for femur fractures was 12 weeks. These findings contradict the results of the study by Berger et al., the series of 68 patients reported the average time for fracture consolidation as 7.9 weeks for forearm fractures, 10.6 weeks for tibia fractures, and 11.9 weeks for femur fractures.12 This coincides with the grade 3 callus according to the criteria of Anthony et al.9,13

In this study, all the fractures healed uneventfully. The Flynn et al., scoring system was used for the outcome measures for femur and tibia fractures.1,7,14,15 In this study, the outcome in 7 patients (26.9%) was satisfactory based on Flynn et al. criteria, while the outcome in 19 patients (73.1%) was excellent. The study had no poor results, comparable to other reported series in the literature.7,15–20 For the forearm fractures, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia forearm fracture fixation outcome classification was used,21 developed by Flynn et al., Table S3. Minor complications were recorded, such as skin irritation due to nail prominence at the entry point, which was tolerable until nail removal.

4.1. Limitations

It includes the retrospective nature of this study, which relied heavily on patient records. The study was also performed at a single centre with a relatively small number of patients and did not compare elastic nail fixation with other surgical methods of treating these fractures.

5. Conclusion

FIN in pediatric LBF is slowly becoming the gold standard for length-stable fractures in children older than 6. Samtah General Hospital is a moderate district hospital with a 150-bed capacity, and this study has attempted to report experience with using TENs in children and adolescents in this hospital. The results show that FIN offers several advantages when a good technique is employed during fracture fixation, including reduced hospital stay and manageable tolerability in most pediatric patients with LBF.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the participants for their voluntary participation, patience, and availability.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Tella Olalekan Azeez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization.

Mansour Mohammed Aldhilan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization.

Competing interests

There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

The Jazan Health Ethics Committee approved the study under approval number 2367.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.