Introduction

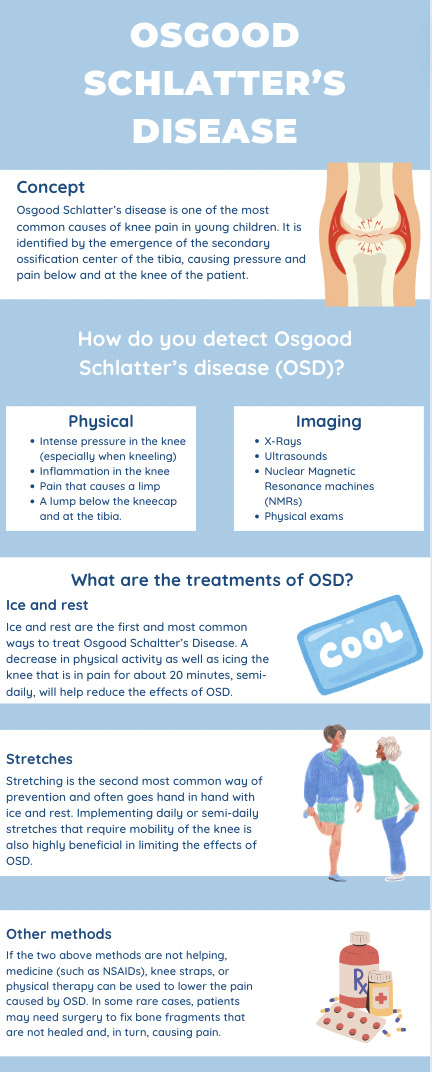

Osgood Schlatter disease was first described by Robert Osgood, an American orthopedic surgeon, and Carl Schlatter, a Swiss surgeon, in 1903 and is one of the most common causes of knee pain in growing adolescents, affecting 1 out of 10 adolescents.1 This disease often develops in young children going through puberty or playing sports. Osgood Schlatter disease (OSD) is characterized by the emergence of the secondary ossification center protruding at the tibia.2 It can also be identified by a small growth right at the tibia and below the patella, via x-ray or other imaging devices. With prevalence rates ranging from 9.8 to 12.9 percent, children from ages 12 to 14 are most susceptible to OSD.1 Although OSD is most often seen in boys ages twelve to fifteen, the sex of the child does not increase the likelihood of developing the disease.3 Patients with OSD often experience intense pressure in the knee (especially when kneeling), inflammation in the knee, pain that causes a limp, and sometimes a lump below the kneecap and at the tibia. Osgood Schlatter’s disease can be detected using imaging and a physical exam.1 Luckily, Osgood Schlatter’s disease bears very few long-term complications. Some adolescents who are diagnosed with OSD may have chronic knee pain or a non-invasive bump on the shinbone. In some rare cases, patients with OSD may cause the growth plate to pull away from the shinbone, leading to a crooked kneecap and lack of mobility in the knee.4 Whether it is decreased physical activity, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), knee straps, or physical therapy, treating OSD is very simple. The most common method is applying ice on top of the knee or implementing daily or semi-daily stretches that improve knee mobility.1

Case Presentation

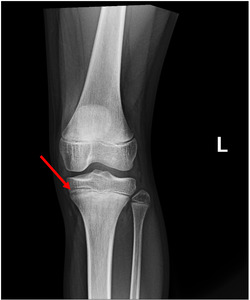

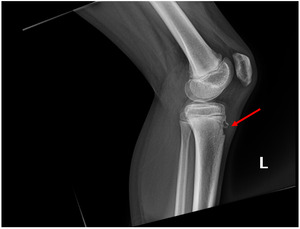

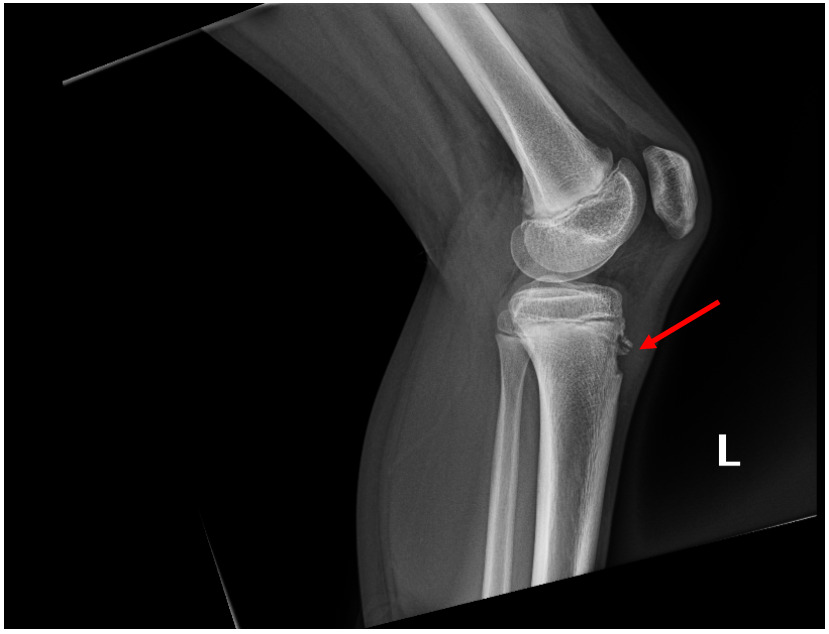

A 10-year-old female came into the emergency department (ED) after complaining about atraumatic knee pain and pressure. The patient had been very active, ran daily, and was slender. She was not unwell in any way and denied any fever, chills, chest pain, shortness of breath, headaches, or urinary problems. A physical examination was conducted and the following signs were found: pulse oximetry levels of 99% on room air, body temperature of 98.0 degrees, a pulse rate of 101 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, and significant pain at the tibial tubercle. Due to the tenderness of the patella, an X-ray of the knee was ordered. The knee radiograph demonstrated a small growth at the tibial tubercle (Figures 1 and 2). This growth was pressing against the shinbone and was the likely cause of pain for the patient.

The patient was discharged and instructed to treat her symptoms by icing the knee for 20 minutes 2-3 times a week, limiting physical activity and her daily runs, and implementing daily knee stretches.

Discussion

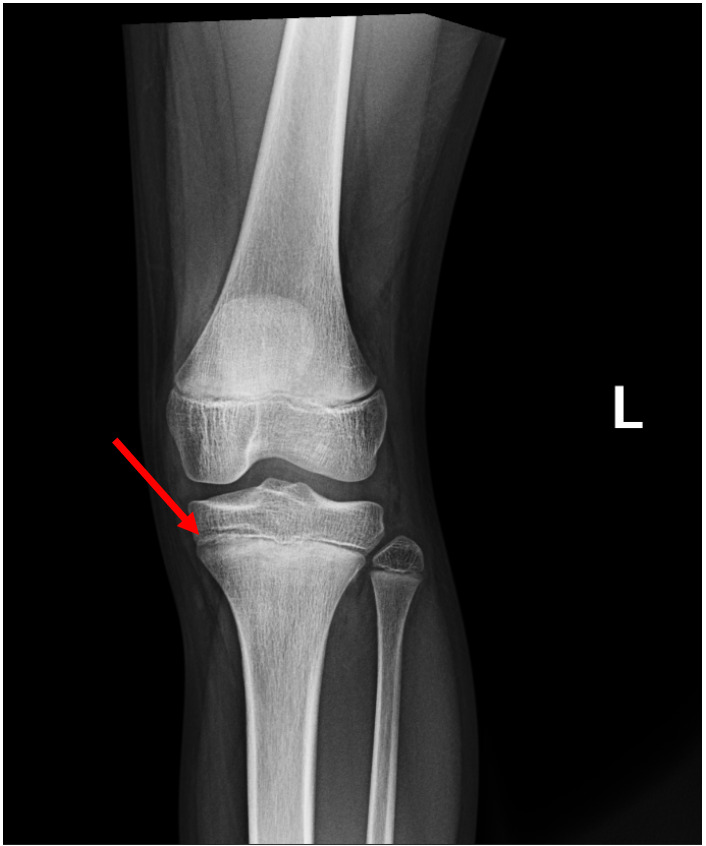

Osgood Schlatter disease (OSD) is characterized by pain at the tibia. Clinical symptoms include pain in the knee and trouble with mobility. Since OSD is often seen in growing kids who practice repetitive physical activities, it is commonly treated by applying ice on the knee, regularly stretching the knee, and limiting physical activity (Figure 3).

This case of an active 10-year-old patient experiencing knee pains with classic physical exam results is indicative of Osgood Schlatter disease. This condition often affects adolescents who are experiencing puberty and are very physically active.2 This patient was sent home to treat the disease with conservative measures such as icing and stretching the knee. In a 2020 study of a cohort of 12 to 15-year-old boys, new risk factors have recently been found that may make individuals more susceptible to developing OSD. These factors include weight (such as obesity), muscle tightness, or muscle weakness in the hamstring muscles. If these factors become extreme, this could not only increase the chances of developing harmful Osgood Schlatter disease but also increase the need for surgical intervention.3 Another recent study of a group of both male and female adolescents has shown that Osgood Schlatter disease resolves spontaneously once the child reaches the end of puberty. After a child with OSD stops growing, the knee will re-adjust and the pressure in the knee will improve. Only in rare and extreme cases, is surgery needed to remove the small growth at the tibia to prevent losing mobility in the patient's knee.5 Suspicion of a pathologic lesion or chronic pain or dysfunction that does not resolve with skeletal maturity are indications for surgical evaluation.6

Conclusions

Osgood Schlatter disease is primarily a self-limited condition seen in adolescents. Physicians and patients should use non-invasive techniques daily to semi-daily to prevent the pain and pressure caused by Osgood Schlatter disease. It is important to note that surgery is only needed in rare cases when OSD affects the mobility of the patient. Otherwise, OSD often resolves once the patient ends puberty.