Introduction

Epidural injections have been used since the early 1900s for treating sciatica and radicular pain, with the caudal approach being one of the earliest methods of accessing the epidural space.1 The use of steroids in the epidural space as a therapeutic approach began in the 1950s and 60s, making ESIs a viable treatment option for low back and radicular pain complaints.2 Steroids can be deposited in the epidural space through various injection techniques to reduce inflammation and provide pain relief. Other methods of performing epidural injections include the transforaminal and interlaminar approaches.

Caudal ESIs are indicated for treating a wide range of conditions including chronic lower back pain, lumbar disc issues, spinal stenosis, and lumbar radicular pain.3,4 The procedure for performing a caudal ESI can vary significantly based on the patient’s specific pathology, anatomical considerations, and the physician’s preferred technique.

Given the lack of standardization among a wide variety of interventional pain procedures we developed a survey to explore specific variables of interest. This study investigates the practice patterns of physicians in various clinical settings who perform caudal ESIs, focusing on medication choices, needle types, and the utilization of catheter-based interventions to treat higher-level pathology. We also assess the clinical safety of caudal ESIs based on these practice techniques.

Methods

A survey examining various practice parameters of physicians conducting epidural steroid injections received approval from the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. The survey was created based on its perceived clinical significance and interest within the interventional pain community. It was distributed via email and online social media groups using an online survey platform to interventional pain physicians in both academic and private practice settings. Physicians were invited to participate anonymously by clicking the provided link and were informed that the survey focused on practice parameters for pain physicians performing ESIs. To prevent duplicate responses, the survey link restricted multiple attempts from the same device. The survey questionnaire was tested by a small group of academic interventional pain physicians for consistency and clarity before distribution.

Given the wide range of topics covered by the survey, key clinical aspects were categorized and will be published separately. Here, we present our findings on the practice styles and technical approaches of physicians who perform caudal ESIs. The questions related to this paper can be seen within Table I.

Results

The survey results are outlined below. Responses were collected from March 1st, 2024, to May 31st, 2024. The survey was distributed via email to academic physicians in ACGME-accredited fellowship training programs and through social media platforms to physicians practicing interventional pain medicine. Due to the multiple distribution platforms including email, web-links, and social media, we can only report on those who initiated and completed the survey, making it impossible to calculate a true response rate. The survey included four specific questions focused on caudal epidural spinal injections and various aspects of practice patterns. These questions addressed the type of steroids administered during the injection, the choice of needle used for the procedure, whether a catheter was utilized to reach higher pathology, and an assessment of major permanent neurological injuries resulting from the procedure to gauge safety.

When evaluating the type of steroids used for caudal ESIs, 72.41% of physicians (63 out of 87) reported using particulate steroids, while 25.29% (22 out of 87) used non-particulate steroids. Only a very small minority either did not administer any steroid (1.15%) or did not perform caudal injections at all (1.15%). These results demonstrate that nearly all physicians perform caudal ESIs with a majority of physicians utilizing particulate steroid in their injections. Of note, a total of 87 physicians completed this question with eight physicians skipping this question. The results are displayed in Figure I.

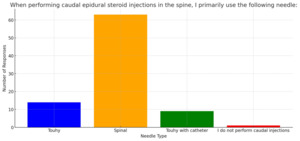

When evaluating needle preference for caudal ESIs, 16.09% (14 out of 87) of physicians reported they use a Touhy needle, whereas 72.41% (63 out of 87) preferred a spinal needle. Another 10.34% of respondents reported using a Touhy needle with a catheter (nine out of 87), and only 1.15% reported they did not perform caudal injections (one out of 87). Of note, only 87 physicians completed this question with eight physicians skipping this question. The results are displayed in Figure II.

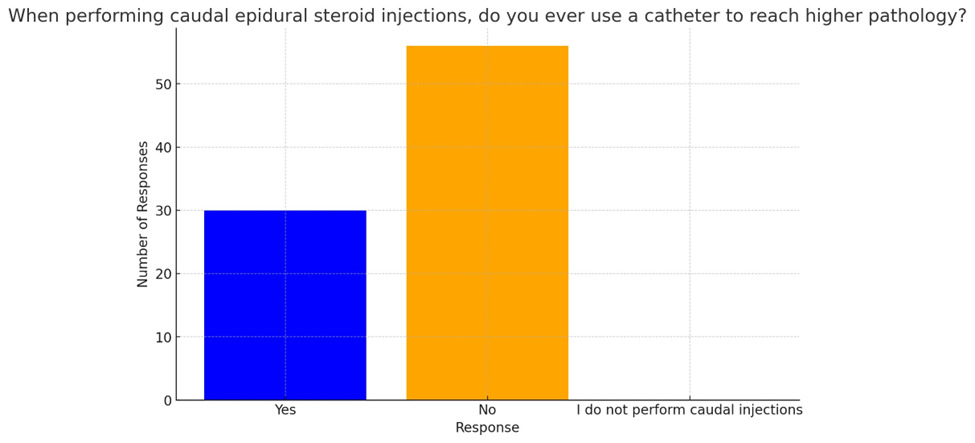

When evaluating the use of catheters to reach higher pathology during caudal ESIs, 34.88% (30 out of 86) of physicians responded affirmatively while 65.12% (56 out of 86) indicated they never use a catheter. This reveals that a majority of physicians do not utilize a catheter during caudal epidural steroid injections. Of note, only 86 physicians completed this question with nine physicians skipping this question. The results are displayed in Figure III.

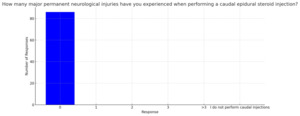

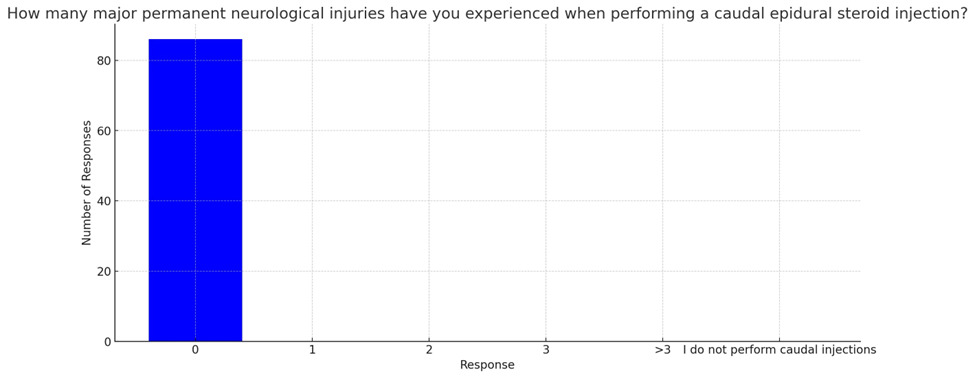

Question four inquiries about major permanent neurological injuries resulting from caudal ESIs. All 86 respondents (100%) reported no instances of such injuries. Of note, only 86 physicians completed this question with nine physicians skipping this question. The results are displayed in Figure IV.

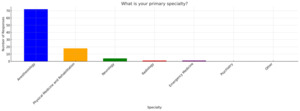

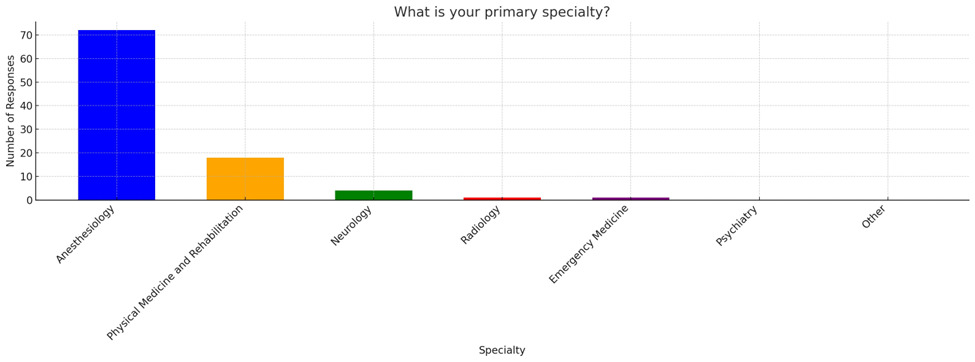

We also provide the following demographic details of the participants including the specialty background of responders along with their practice setting as we believe this may provide additional insight to these answer choices. No other demographic details were obtained during this survey. Figure 5 reveals that 75% of physician responders are Anesthesiologists (72 out of 96). This is followed by 18.75% of physicians who are Physiatrists (18 out of 96). Neurologists made up 4.17% (four out of 96). Finally, 1.04% of responders were Radiologists (one out of 96) with another 1.04% Emergency Medicine physicians (one out of 96). The results are displayed in Figure 5.

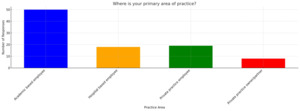

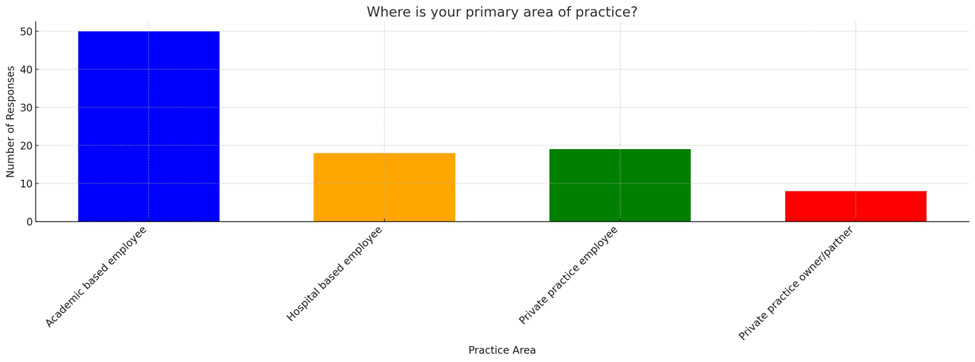

Figure VI reveals that 52.63% of physician responders are academic based physicians (50 out of 95). Another 18.95% of physicians are hospital-based employees (18 out of 95). Private practice employed physicians made up 20% of responders (19 out of 95) Finally, 8.42% of responders were owners or partners in a private practice (eight out of 95). Of note, one physician skipped this question. The results are displayed in Figure VI.

Discussion

The caudal approach to the epidural space, dating back to the early 1900’s and gaining international popularity by 1925 for treating sciatica, represents one of the earliest techniques for performing ESIs.5–8 Evans’ pioneering study on caudal epidural injections initially showed promising outcomes for lumbosacral pain by physically displacing nerves and breaking down neuronal adhesions.1 Corticosteroids were later integrated with local anesthetics, establishing the standard epidural steroid injection for acute and chronic pain management. Despite abundant literature on ESIs, notable controversy remains regarding their safety, efficacy, and standardization of practice.9 This study aims to characterize the practice patterns of interventional pain physicians across multiple specialties and practice settings regarding caudal epidural steroid injections, focusing on specific aspects such as steroid choice, needle selection, catheter usage for accessing higher pathology, and incidences of major permanent neurological injuries as a safety indicator.

Steroid Selection

Caudal ESIs are widely used to manage low back pain and sciatica. Providers typically administer 5-25 mL of injectate, adjusting volumes based on patient characteristics, catheter use, and spinal level to be treated. Common analgesic combinations include a local anesthetic such as bupivacaine or lidocaine with varying doses of steroids.9,10 Research comparing particulate versus non-particulate steroids for caudal ESIs is extensive, though dosing guidance remains limited. Methylprednisolone and triamcinolone are classified as particulate steroids, while dexamethasone and betamethasone are non-particulates.11

Intravascular injection of corticosteroids or local anesthetics can lead to serious adverse effects, with inadvertent intravascular injection rates during fluoroscopically guided transforaminal epidural steroid injections (TFESIs) ranging from 9% to 32.8%, depending on the injection level.12 Particulate corticosteroids are particularly associated with complications such as vascular embolism, spinal cord infarction, and paraplegia, with some cases involving the artery of Adamkiewicz.13–17 Non-particulate corticosteroids, being soluble, present a lower risk of such embolic events.18 Although studies indicate that there is no significant difference in efficacy between particulate and non-particulate steroids, the latter is preferred due to its reduced risk of serious complications.18–21

TFESIs are associated with a higher risk of serious adverse effects such as lower limb neurologic deficits, compared to caudal ESIs, primarily because TFESIs position the needle closer to the nerve root and radicular artery.22,23 This proximity increases the risk of embolism from particulate steroids, which can lead to spinal cord infarction.22,24 However, using non-particulate, soluble steroids in TFESIs has been shown to mitigate these risks while maintaining comparable clinical outcomes.25 Thus, non-particulate steroids may help alleviate concerns about severe side effects and reduce the reluctance to perform TFESIs.11 Conversely, caudal ESIs may present with fewer risks, such as minimal chance of intravascular injection, nerve injury, or dural puncture, while remaining effective clinically.26–28

In our survey of interventional pain physicians, 72.41% of those who responded preferred utilizing particulate steroids, while 25.29% opted for non-particulate steroids. Datta et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing caudal methylprednisolone acetate, triamcinolone acetonide, and dexamethasone acetate, finding no statistically significant difference in pain relief efficacy between them.29 Kim et al.'s meta-analysis indicated no significant difference in pain intensity or disability scores between particulate and non-particulate steroid injections for lumbar radicular pain, though particulate steroids showed better pain relief in randomized controlled trials (MD=0.62; 95% CI 0.08-1.16, P=.02), with methylprednisolone showing better effects than dexamethasone, and dexamethasone better than betamethasone in subgroup analysis.30

Makkar et al.'s systematic review concluded that non-particulate steroids are equally effective based on validated pain scores, while El-Yahchouchi’s study suggested comparable efficacy between particulate and non-particulate steroids for transforaminal epidural injections.19,31

The preference to utilize particulate steroids when performing caudal ESIs may be related to decreased risk of intravascular injection or radicular artery injury and a physician’s personal preference or bias that particulate steroids are more efficacious. This is of interest as there were no reported cases of permanent neurologic injuries or embolic infarction, regardless of steroid selection, after caudal ESIs.

Needle Selection

In our study, 72% of providers preferred using spinal needles over Tuohy needles or Tuohy needles with catheters. Many pain physicians favor sharp, beveled spinal needles like the Quincke or Chiba needle for their ease of maneuverability and advancement. Spinal needles may be preferred because they are thinner, causing less discomfort when accessing the caudal space. Pencil-type needles such as the Whitacre needle have a lower intravascular injection rate but are more challenging to manipulate and associated with longer procedure times compared to Quincke needles.32 Blunt-tip needles, despite their low intravascular injection rate, lack a bevel, making steering and tissue penetration difficult and potentially increasing patient discomfort.33

Research comparing needle types shows varying intravascular injection rates between Tuohy and Quincke needles. Soh et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing these needle types for TFESIs, noting a significantly lower intravascular injection rate with Tuohy needles compared to Quincke needles (2.9% vs 12.7%, p=0.009), along with higher rates of epidural spread in the Tuohy group.34 Although Tuohy needles were not the primary choice among providers in our study, their favorable safety profile in other procedural approaches suggests they may be a safer needle option. However, further large-scale studies specifically focusing on caudal ESIs are needed to explore intravascular injection rates at this spinal level. With more evidence-based insights into needle safety, physicians can confidently select appropriate needles for caudal ESIs, minimizing procedural risks.

Catheter Utilization

Epidural catheters can be used to target higher-level pathology, such as pain related to lumbar disc herniation. In our survey, 34.88% (30 out of 86) of providers employed catheters during caudal ESIs, while the majority did not. Catheters can offer advantages, such as accessing spaces difficult to reach with interlaminar or transforaminal approaches, providing more targeted delivery of steroids in smaller volumes, and potentially mechanically breaking up adhesions. However, their use comes with increased procedure time, the need for larger needles for catheter insertion, risks of infection, potential for increased patient discomfort, and the possibility of dural puncture if the catheter is advanced aggressively. Yin et al.'s study demonstrated that catheter use in caudal ESIs can effectively reduce pain and disability compared to non-catheter approaches, attributed to precise steroid delivery.35 Despite these benefits, the reluctance of many providers to use catheters remains, and future studies should focus on refining catheter deployment guidelines and enhancing safety through qualitative and quantitative data.

Procedural Injuries

ESIs have been utilized for several decades with a history of rare serious complications such as allergic reactions, bleeding, infection, nerve damage, or paralysis, underscoring the need for skilled administration under image guidance by experienced physicians to minimize risks.36 Accessing the epidural space via the sacral hiatus is typically straightforward in patients with typical anatomy. However, challenges such as abnormal sacral curvature or obesity can complicate the procedure, especially without fluoroscopic assistance. Issues like needle misplacement leading to injections outside the sacral canal can occur without the use of fluoroscopy or contrast which will confirm appropriate needle placement and epidural spread of medications. Non-fluoroscopic techniques increase the risk of traumatic needle placement and intraosseous injection. Fortunately, severe effects are uncommon with typical injection volumes (5-20 cc).9

In this study, all providers reported no major permanent neurological injuries associated with caudal epidural spinal injections. The low numbers of major permanent neurological injuries are likely related to decreased risk of intravascular injection or radicular artery injury when accessing the sacral hiatus along with reduced risk of dural puncture.

Limitations

Similar to other surveys, our study has notable limitations. Due to the multiple distribution platforms including email, web-links, and social media, we can only report on those who initiated and completed the survey, making it impossible to calculate a true response rate. Some physicians opted not to complete the entire survey or may have skip questions. This has been reported for each specific question. Additionally, a significant proportion of our physician respondents practice in academic hospitals, potentially introducing a sampling bias that necessitates consideration when interpreting our findings. Furthermore, variations in question wording may have influenced respondent perceptions and, consequently, their answers. Nonetheless, we believe these findings offer valuable preliminary data for establishing practice parameters for interventional pain physicians who perform caudal ESIs.

Conclusion

Epidural injections, particularly caudal ESIs have been a popular interventional technique for treating chronic low back and radicular pain complaints. This study highlights the diversity in practice patterns among physicians, showing variations in steroid choices, needle types, and catheter usage. Of note, this study demonstrates that caudal ESIs have a low risk of major neurological injuries regardless of procedural technique. Further research comparing outcomes of caudal ESIs using particulate and non-particulate steroids and exploring different needle types could improve procedural techniques. Understanding when catheter use is beneficial may lead to more standardized practices. Standardizing practices based on evidence can enhance the precision and effectiveness of caudal ESIs. Collaborative research for standardization of practices in interventional pain management may ultimately improve patient outcomes in managing lumbosacral pain complaints.