Introduction

The wrist, composed of the distal radius, distal ulna, and carpal bones, plays a significant role in children’s motor skills and daily activities. Wrist fractures can influence early childhood development and impact future mobility.1 Healthy wrist function is essential for various daily activities such as writing, playing sports, and other activities involving general motor movement. Significant wrist fractures commonly seen in pediatric patients include Seymour fractures2 open juxta-epiphyseal fractures of the distal phalanx, Mallet fractures, Phalangeal neck fractures, and Scaphoid fractures.3,4 Wrist fractures make up 25% of all fractures in children and can affect a child’s growth plates, which can lead to long-term development complications if not properly attended to.3

Distal Radius fractures are the most common pediatric wrist fracture, classified as a fracture to the radius near the wrist area.5 This fracture often results from falling on an outstretched hand or accidents through sports.6,7 Apart from distal radius fractures, other common fractures include buckle or greenstick fractures [provide reference?]. These types of fractures occur when the bones are pressured or bent. These forms of wrist fractures are common in children due to the flexible nature of their fragile, still developing bones.8 Some primary differences in pediatric versus adult fractures are the diagnosis, treatment, and healing due to the presence of growth plates.9 Prompt and accurate diagnosis is crucial to prevent complications such as growth disturbances and functional disabilities, as well as permanently impairing a child’s wrist and motor ability.

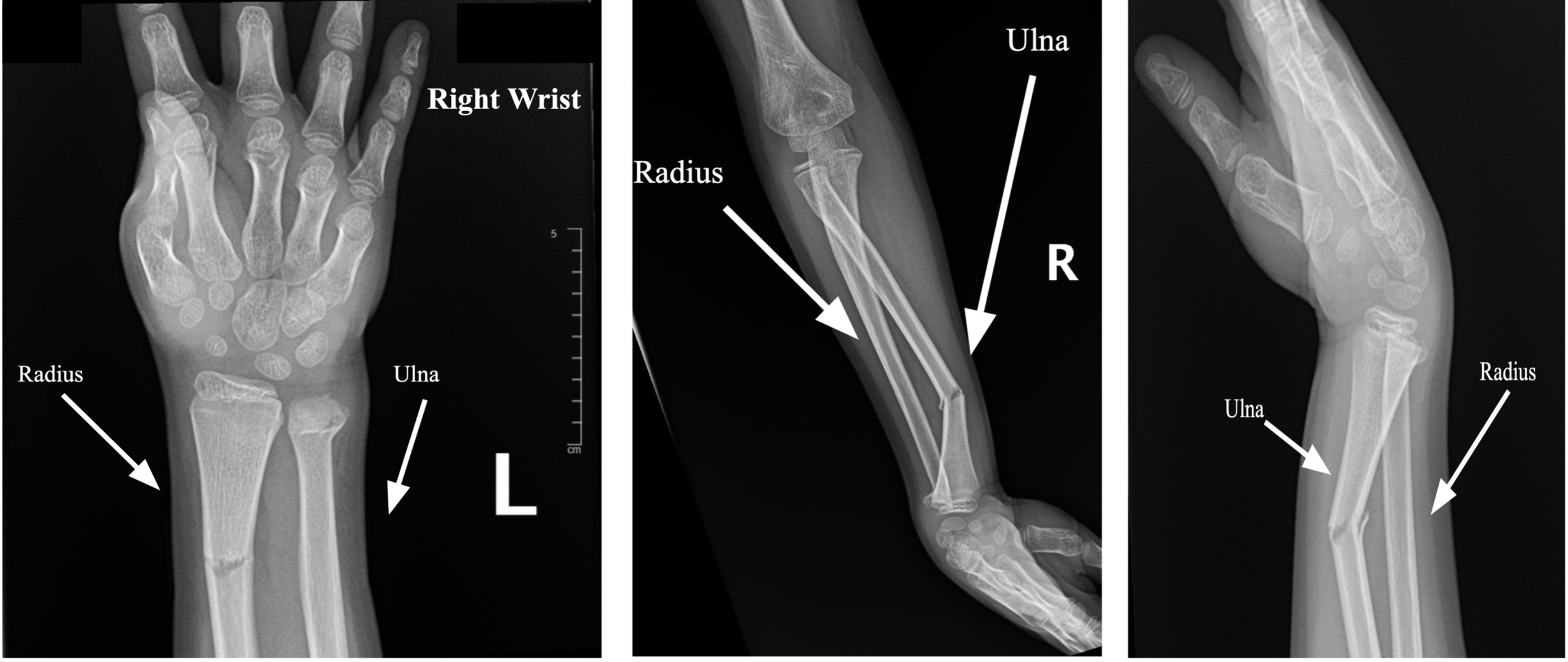

Treatment options range from casting and splinting for minor cases to surgical intervention for more complicated cases10 [Figure 1]. Advancements in imaging techniques, magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs), significantly improve the accuracy of diagnosing pediatric wrist fractures and contribute to better treatment planning.11 Other treatment method advancements are surgical and non-surgical innovations.1 Innovative treatment approaches, including minimally invasive surgical techniques and improved casting materials, have enhanced recovery outcomes for pediatric patients. Despite this advancement in treatment, there remain gaps in the understanding and management of pediatric wrist fractures, such as surgical management, which has limited scientific evidence.10 This paper will describe the epidemiology, diagnosis, treatments, and long-term consequences of pediatric wrist fractures, highlighting the need for more tailored, evidence-based approaches to improve pediatric orthopedic care.

Case Presentation

A six-year-old boy was brought into the emergency department after an incident at the trampoline park. The family was leaving, but the child did not want to and resisted. The patient was reluctant to leave his parents, leading to him further injure himself by landing on his right wrist. The patient was neurovascularly intact, and no arm pain was reported unless movement occurred. The patient had no past medical history or allergies.

The patient’s vital signs were: pulse 119 bpm, respiratory rate at 20 breaths per minute, temperature at 97.8°F, and oxygen saturation 100%. The patient’s tachycardia was likely due to the pain, distress, and anxiety in the moment. On physical exam there was significantly reduced range of motion of the wrist and forearm and deformity. No open fracture was present, nor was there any absence of the radial pulse, ulnar pulse, or neurological function. Two doses of Ibuprofen were administered for analgesia.

Radiographs demonstrated mildly comminuted displaced mildly angulated right distal radial and ulnar metaphyseal fractures [Figure 2].

Discussion

A comminuted bilateral fracture of the radial and ulnar portions of the wrist, specifically in a pediatric patient, presents additional risks compared to adult bilateral comminuted fractures when the growth plates are involved.12–14 The distal radius wrist fracture is categorized as one of the most common fractures, making up a sixth of all Emergency Department visits and 26-46% of all skeletal fractures in America.14 Children’s bone density is much lower than that of adults, classifying them as far more porous than adult bones.3 It is crucial to consider the distal ulnar epiphysis (DUE), as it does not ossify until six years of age. This difference results in the fracture damaging the child’s wrist more, leading to growth disturbances due to partial damage or possibly an angular deformity.15 Furthermore, damage to the epiphyseal plate brings greater risk in a developing pediatric patient.16

One primary concern is the damage to the growth plates along the distal ulnar epiphysis. Due to a thicker, more active periosteum, the damaged growth plates could significantly impact the growth of the child’s wrist. This concern is due to the ligamentous and distal ulnar fractures that may develop into long-term instability. Finding an acceptable reduction, or precise alignment of broken bone fragments, when epiphyseal plates, the areas of growth tissue near the ends of long bones in children, are fractured is problematic because it is dependent on the initial angulation, or the angle at which the bone was displaced. If the initial angulation is greater than 30 degrees to the sagittal plane, it significantly increases the risk of poor healing.2

Instead, it is recommended to use casts or splints for treating children under ten years old, regardless of the initial angulation, as long as there is no associated ulnar fracture. In pediatric fractures, even if there is angulation when the splint or cast is applied, the growth potential of the epiphyseal and metaphyseal areas often supports bone realignment naturally as the child grows. Unlike fractures in adults, which lack this growth potential, pediatric fractures can realign through growth, allowing treatment such as cast or split to be more effective.

However, while pediatric wrist fractures generally have a more favorable prognosis due to this growth potential, careful management is still essential to prevent future growth complications or deformities. Understanding these differences is crucial for optimizing treatment strategies and reducing long-term risks for pediatric wrist fractures.9

Conclusion

Pediatric wrist fractures occur for several reasons, with falling and sports accidents amongst the primary causes. Attention to proper realignment of displaced and angulated fragments is important, as is attention to developing growth plates.