Introduction

Primary TKA in a patient with a chronic total patellectomy is uncommon, and limited research exists. The patella is essential for knee function. It enhances the extensor mechanism’s leverage and facilitates smooth knee extension. A unique challenge in TKA with chronic complete patellectomy significantly impacts this mechanism and knee function.1,2

The effective pain management is necessary for recovery in this complicated patient.3 A significant factor in cases of previous patellectomy is the altered biomechanics and soft tissue conditions, which can increase pain and complicate pain management strategies. This report describes a 74-year-old man with The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification II and a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of 0 who underwent total knee arthroplasty (TKA) following a complete patellectomy.

Patellar reconstruction in such cases is complex. Using allografts carries risks of donor site morbidity, disease transmission, and potential graft failure. While Busfield BT et al.4 showed that patellar allografting improved quadriceps function by restoring patellar height, this procedure is associated with a high rate of complications.

Synthetic materials, such as prosthetic knee components, are an option but can wear out, become loose, or get infected. Previous studies have shown that various approaches have varying success rates for using posterior cruciate-substituting prostheses or cruciate-retaining implants in patients with old patellectomy.

Cameron HU et al.5 concluded that a posterior cruciate-substituting prosthesis gives reasonable results in patients without a patella. Reinhardt KR et al.6 reported their case series of TKA in patients with prior patellectomy. They showed good survivorship and functional outcomes with a cruciate-retaining prosthesis at a mean follow-up of 11.2 years. In a study by Joshi AB et al.,7 total knee arthroplasty outcomes were compared between 19 patients with a prior patellectomy and a matched group of patients with an intact patella. After an average follow-up of 63 months, the patellectomy group had a 36% complication rate, including poor outcomes, instability, persistent pain, and even fractures. The control group had no complications and complete pain relief. These results strongly suggest that a prior patellectomy increases complications and less successful outcomes.

Chronic complete patellectomy presents a significant challenge in TKA. Restoring the function of the extensor mechanism without the native patella is difficult. The absence of a patella disrupts normal knee biomechanics. Lakshmanan P et al.8 described a novel technique for patellar reconstruction using the tibial plateau obtained from the routine tibial cut during TKA. They reported improved functional outcomes in patients undergoing extensor mechanism reinforcement, with the benefit of avoiding an additional procedure and its associated morbidities to harvest a bone graft.

The functional neo-patella should provide for a stable and well-functioning knee, causing minimal complications and giving the best outcome. In this patient, we used an innovative technique of taking a small piece of bone from the femoral condyle cut to create the neo-patella. This approach does not need donor tissue. However, the femoral condyle bone is 8 mm thick, so it is necessary to resurface the patella with polyethylene and cement and suturing to the extensor mechanism. This procedure can result in lower complications and lead to a better recovery in the long run. We report a unique case requiring TKA and patellar reconstruction due to a prior accident resulting in a complete patellectomy.

Case Presentation

Ethical Considerations

The Human Research Ethics Committee of Ratchaburi Hospital approved this study (approval number COE-RBHEC 001/2024). The patient provided informed consent.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old man with a history of open knee injury and subsequent complete patellectomy 40 years ago presented to Ratchaburi Hospital in 2017 with bilateral knee pain. He used crutches for 40 years and was unemployed. The patient was generally healthy but had high blood pressure treated with amlodipine 5 mg and frequently used NSAIDs for knee pain. Their overall health was classified as ASA II, and they had no major heart risk factors (RCRI score of 0). He underwent left TKA in December 2017 and plans to get the right TKA in 2019. The COVID-19 pandemic delayed a schedule until February 2022, when it was finished.

Preoperative examination of the right knee revealed a range of motion of 0-120 degrees with passive extension, 10 degrees of extensor lag, and intact medial and lateral collateral ligaments.

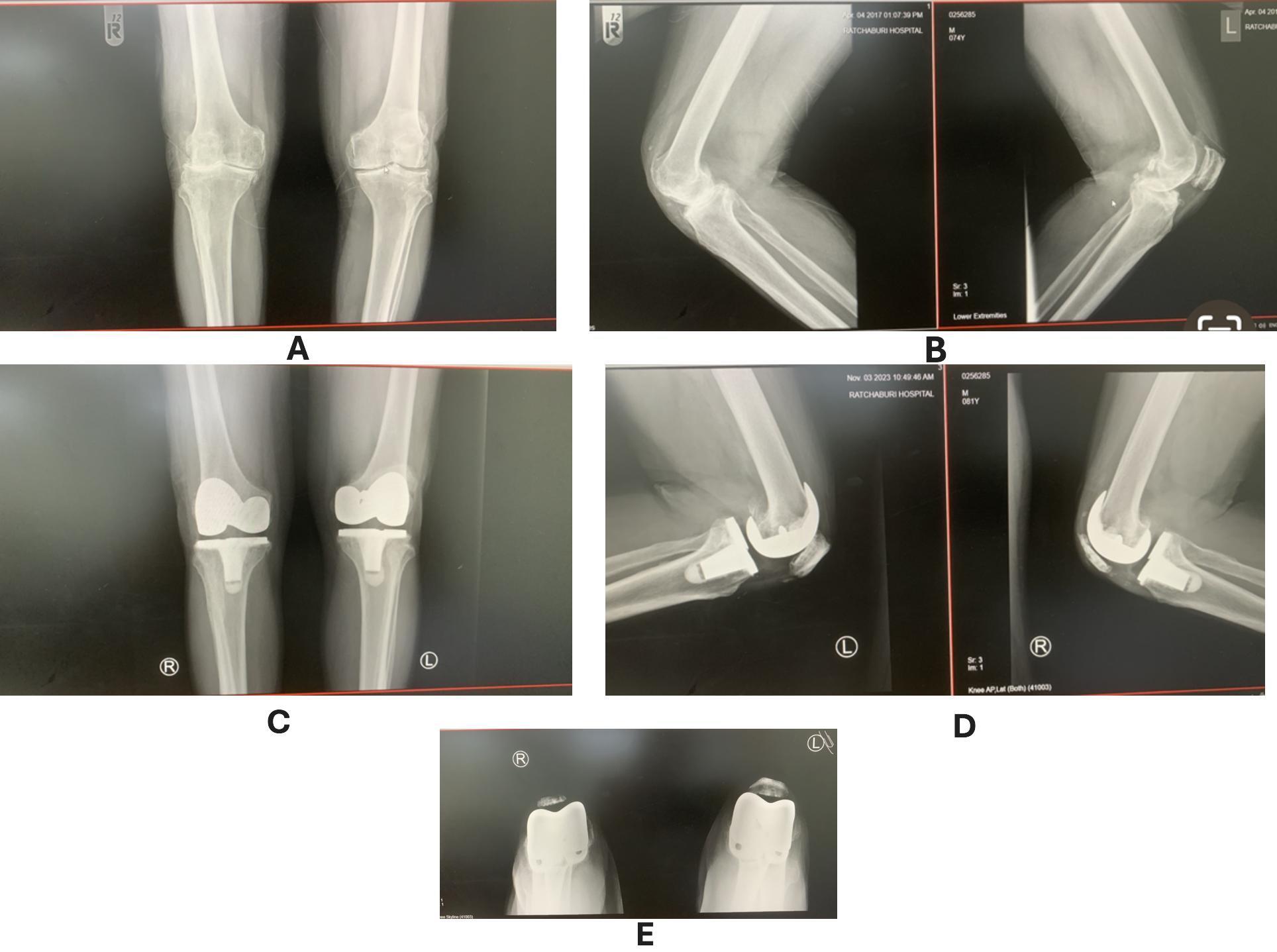

There was no neurovascular compromise. The patient received combined spinal anesthesia and a femoral nerve block during surgery. Following physical and radiographic assessment, the patient underwent TKA with a cemented, fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized prosthesis (NexGen LPS Fixed Bearing Knee, Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, Indiana, USA). An 8-mm autologous bone graft harvested from the medial distal femoral condyle was utilized for patellar reconstruction. This neo-patella was resurfaced with a cemented patellar prosthesis and sutured to the extensor mechanism. The patient was closely monitored. Two years after surgery, his knee fully functions without pain and could bend from 0 to 120 degrees, the same as his contralateral knee. The radiograph showed no signs of graft migration or resorption.

Surgical Technique

After the anesthesiologist administered spinal anesthesia and a femoral nerve block, the operation was performed. A standard midline incision was made, incorporating any existing scars. The knee joint was operated through a medial parapatellar approach. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, the distal femur and proximal tibia were resected before cementing the TKA prosthesis. Despite its 8-mm thickness and cartilage loss, the medial distal femoral condyle was selected to create neo-patella due to its superior bone stock. After removing osteophytes and cartilage, the condyle was fashioned into a 6-mm coin-shaped bone graft. Four small holes (1.5 mm each) were made in the corners of the graft to attach it with stitches. The graft was then fixed to the patellar prosthesis with cement.

Based on the study by George DA et al.,9 the neo-patella was placed 10 mm distal to the femoral component apex, ensuring proper centering within the trochlear groove. The neo-patella was then sutured to the extensor mechanism using the previously placed 3-0 Vicryl suture. With the proximal pole of the neo-patella 10 mm distal to the implant apex, this positioning optimized patellofemoral mechanics, ensuring engagement with the trochlear groove throughout the range of motion. No patellar mal-tracking was observed, and the knee was stable after trial reduction. (Figure 1)

A surgical drain was placed, and the incision was closed. A long leg slab was applied for immobilization. The drain was removed on postoperative day three, and the patient began non-weight-bearing ambulation. Sutures were removed at two weeks and replaced with a long leg cast for six weeks.

A rehabilitation program, including quadriceps exercises and active knee range of motion, was initiated at 8 and 12 weeks postoperatively. Postoperative radiographs demonstrated a well-aligned prosthesis. At eight weeks, the patient started full weight-bearing ambulation. By twelve weeks, the patient achieved a range of motion of 0-120 degrees with excellent patellar tracking and no effusion. Two years later, the neo-patella was still in place and showed no resorption or migration on radiography. (Figure 2) The Oxford Knee Society Score was 45, and the Feller Patella Score was 26. The postoperative alignment and range of motion for his knees are shown in Figure 3.

Discussion

Prior patellectomy significantly increases the complexity and risks associated with TKA. Table 1 summarizes the critical factors to consider during neo-patella reconstruction. Allografts or staged reconstruction may be necessary for patients with poor soft tissue quality or inadequate extensor mechanism remnants. While previous studies have described various allograft techniques for patellar reconstruction, these carry inherent risks of infection and failure.4,10

Paletta GA et al.11 reported no revisions in posterior-stabilized or cruciate-retaining implants following patellectomy, though outcomes were less favorable with cruciate-retaining implants. Similarly, Dhaiya V et al.12 found good midterm results with cruciate-retaining TKA in patients with prior patellectomy.

Tirveilliot et al.13 performed TKA with cemented polyethylene resurfacing using a tibial plateau autograft and reported mid-term graft migration and poor outcomes. They advocate for trans-osseous suture fixation.

Pang et al.14 reported a successful patellar reconstruction. They used an autograft from the distal femoral condyle and non-resurfacing. Two years after surgery, the patient had excellent results. Conversely, Daentzer D et al.15 reported a higher complication rate (including infections and fractures) with iliac graft reconstruction, highlighting the potential for increased donor site morbidity.

The ideal graft thickness for patellar reconstruction is typically 22-26 mm, with a minimum of 12 mm after resurfacing to prevent fracture.9 In this case, due to limited bone availability from the medial femoral condyle, an 8-mm autograft was harvested, resurfaced with a cemented patellar prosthesis, and securely fixed to the extensor mechanism using 3-0 Vicryl sutures. This resulted in a final construct thickness of 16 mm, demonstrating adequate intraoperative stability.

The 3-0 Vicryl suture was based on several factors, including the patient’s low activity level, good general health, and well-preserved extensor mechanism tissue. 3-0 Vicryl provides sufficient initial strength for secure fixation while minimizing suture prominence and the risk of foreign body reaction associated with non-absorbable sutures. While more robust suture options might be necessary for younger, more active patients, 3-0 Vicryl is appropriate for this patient. The key to success is careful surgical methods—the proper neo-patella implantation with secure fixation. A long leg cast after surgery provided immediate and continuous stability, facilitating tissue integration and remodeling.

Sancheti KH et al.16 highlighted the importance of a preoperative range of motion and functional status in achieving positive outcomes. The surgeon should inform the patient of these factors and their potential impact.

Sarridou D et al.17 demonstrated the benefits of intravenous parecoxib in enhancing postoperative analgesia and rehabilitation after TKA.

This patient was a tailored rehabilitation program with a gradual progression of exercises and weight-bearing. At two years postoperatively, the patient demonstrated excellent outcomes. His knee had no pain and could flex from 0 to 120 degrees, and X-rays showed no graft resorption, migration, or fracture. This case report has limitations. The lack of intraoperative images and reliance on a saw-bone model for demonstrating the surgical technique may limit the accurate portrayal of the procedure. Because this case is rare and involves only one patient, our findings may have limited generalizability. More research with extended follow-up is needed to see if this technique works well after two years. Future research, including larger populations, intraoperative imaging, and extended post-surgical outcome measures, can improve and achieve good long-run outcomes. The determination of optimal suture choices and fixation techniques for this complicated patient must be based on further study of the future evidence base.

Conclusion

Primary total knee arthroplasty in a patient with chronic total patellectomy using femoral condyle autograft for patellar reconstruction, cementing resurfaced, and suturing to extensor mechanisms increased knee function at 12 weeks and two years postoperatively. This novel operation is a good option for patients with chronic patellar bone loss having total knee arthroplasty.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. Oramon Bamroongshawgasame for implementing information tools to evaluate this paper’s data and assisting in the research discussion.

Author Contributions

Thana Bamroongshawgasame (TB): Study Design, Data Collection, Literature Review, Writing Manuscript, Editing Manuscript, Final Manuscript Approval, and Submit Manuscript

Conflicts of Interest

The author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funds

No funding