1. Introduction

Osgood-Schlatter disease (OSD), also called tibial tuberosity osteochondritis or tibial tuberosity apophyseal osteonecrosis, was first identified in 1903 by American orthopedic surgeon Robert Osgood and Swiss surgeon Carl Schlatter.1 OSD is characterized by swelling and pain at the tibial tuberosity, which worsens after physical activity. It typically occurs in adolescents aged 11 to 16 years and is more common in males than females. It is frequently seen among professional athletes and young military trainees. With the increasing popularity of sports, the incidence of this condition has risen, currently estimated at about 17%.2 The pain associated with this disease significantly affects the quality of life and athletic performance of affected children.1,3

Currently, there is still controversy in the academic community regarding the causes of OSD, and more research is needed to provide evidence.4 Some scholars believe that local trauma leads to this condition,5,6 while Yusuke Murayama and others argue that tightness of the quadriceps does not contribute to OSD. Instead, they suggest that the maturity of the tibial tuberosity is the only independent risk factor.7 However, some scholars believe that the repeated pulling of the tibial tuberosity by the contraction of the quadriceps is related to the occurrence of this condition.8–10 As a result, there is no consensus internationally on the treatment approach for this condition.11

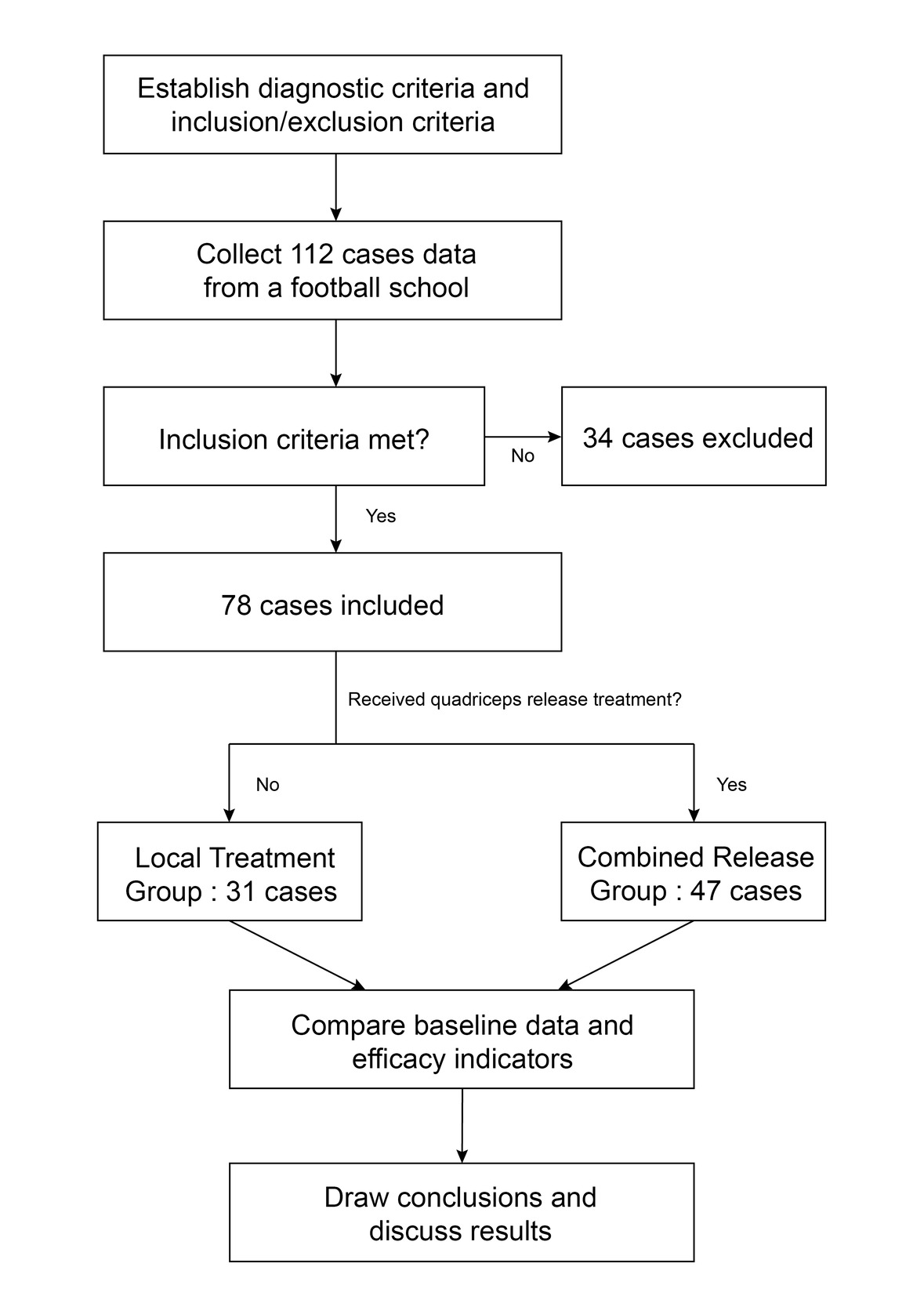

Therefore, there had been differences within the author team in the past regarding the treatment of OSD. Some patients were treated only at the affected area, while others also received additional quadriceps tension release.The authors conducted a retrospective analysis of 78 OSD cases to evaluate the impact of quadriceps tension release on treatment. This study also aimed to better understand the relationship between OSD and quadriceps tension to optimize treatment strategies. The research approach is shown in Figure 1.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design and patient population

The authors collected data from patients with OSD monitored at a football school from May 2020 to December 2023. A retrospective cohort study included 78 patients who met the inclusion criteria. The patients were divided into a Local Treatment Group and a Combined Release Group based on whether they received quadriceps release treatment.The Local Treatment Group included 31 patients who received only local treatment for the affected area. The Combined Release Group consisted of 47 patients who received quadriceps release treatment for the affected limb, in addition to local treatment for the affected area.Compare the baseline data and efficacy indicators of the two groups.

2.2. Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnostic criteria for Osgood-Schlatter disease are formulated with reference to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision.12

2.2.1. It is more common in adolescents with an open tibial tuberosity and high activity levels, with a higher prevalence in males than females.

2.2.2. Bilateral occurrence is common, and most patients have a history of trauma or intense exercise.

2.2.3. Pain at the tibial tuberosity, with increased pain after vigorous activity.

2.2.4. Swelling and tenderness at the tibial tuberosity, with a positive resisted knee extension test.

2.2.5. X-rays and CT scans show: dense bone quality at the tibial tuberosity, irregular shape, and even fragmentation.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

Meets the above diagnostic criteria; age ≤ 18 years; experiencing severe pain that prevents normal training and competition; has not used oral medications or external treatments within the past two weeks.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

Individuals who have received intra-articular injections for the knee joint in the past three months, have a history of knee surgery, or have lower limb fractures, ligament or muscle damage around the knee, intra-articular infections, or tuberculosis; as well as those with other diseases that significantly affect their condition, and individuals who have taken medications that negatively impact their condition, will be excluded.

2.5. Treatment Methods

Treatment for the quadriceps muscle of the affected limb refers to the use of one or more of the following methods to relieve tension in the quadriceps: electroacupuncture,13 Deep Muscle Stimulator(DMS),14 thigh release massage,15 rehabilitation training,16 and kinesiology tape,17 all of which can relieve muscle tension. Local treatment of the tibial tuberosity involves one or more methods to target the surrounding tissues, including ultrasound therapy,18 shortwave therapy,19 laser therapy,20 topical medications,21 local massage,22 ice application,23 all of which are effective in reducing inflammation and alleviating pain. All aforementioned methods are utilized according to established treatment guidelines.

2.6. Efficacy Observation Indicators

2.6.1. The indicators include the treatment duration and the number of sessions needed for patients to resume normal training or competition without pain.

2.6.2. Another indicator is whether the patient experiences a relapse and the time interval between recovery and the subsequent relapse.

2.6.3. Safety indicators: Whether there are adverse reactions in the systemic and anterior knee skin areas during the treatment process in both groups of patients.

2.7. Statistical Methods

Patient demographic information and clinical outcomes are presented either as medians accompanied by interquartile ranges (spanning the 25th to 75th percentiles) or as means with standard deviations (SD). The data are also outlined in terms of counts along with their respective percentages across various categories. For data that did not conform to a normal distribution, Mann–Whitney U tests were employed, while independent two-tailed t-tests were utilized for comparing datasets that adhered to a normal distribution. Differences in categorical data were assessed using Chi-square tests, with results reported in terms of counts and percentages. If the assumptions for the Chi-square test were not met, the Fisher exact test was utilized instead. Data were processed using jamovi 2.4.11 statistical software, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

2.8. Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Hospital Ethical Committee ( Approval No. YJS[2025]-37).

3. Results

Baseline Data: the Local Treatment Group consisted of 31 cases, including 29 males and 2 females. The ages ranged from 10 to 18 years, with an average of 12.8 years (±2.16). The duration of illness varied between 1 and 14 days, with an average of 2.81 days (±2.55). Affected sites included bilateral involvement in 6 cases, left-sided in 17 cases, and right-sided in 8 cases. The Combined Release Group included 47 cases, comprising 45 males and 2 females. Ages ranged from 10 to 16 years, with an average of 12.9 years (±1.39). The duration of illness varied from 1 to 7 days, averaging 2.09 days (±1.21). Affected sites were bilateral in 12 cases, left-sided in 23 cases, and right-sided in 12 cases.Comparisons between the two groups revealed no statistically significant differences in age (t = 604, P = 0.196), duration of illness (t = 605, P = 0.181), gender (χ² = 0.185, P = 0.667), and affected sites (χ² = 0.436, P = 0.804), all with P > 0.05. The average number of local treatments in the Local Treatment Group (1.94±0.51) was greater than that in the Combined Release Group (1.04±0.66), with a t value of 237 and a P value of <0.001, indicating a statistically significant difference (P<0.05).See Table 1 for details.

Efficacy Comparison: The Combined Release Group had an average recovery time of 1.55 weeks (±1.23) and underwent an average of 3.17 treatments (±3.63), both of which were lower than the Local Treatment Group’s average recovery time of 3.58 weeks (±4.26) and the number of treatments at 5.77 (±5.47). The t values were 375 and 464, respectively, with P values of <0.001 and 0.006, indicating that the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Both groups experienced recurrences, with 16 cases (34.0%) in the Combined Release Group and 11 cases (35.5%) in the Local Treatment Group, indicating similar recurrence rates between the two groups. The χ2 value was 0.017, and the P value was 0.896. The Time to Relapse for the Combined Release Group was (4.88±5.00) months, while for the Local Treatment Group it was (6.91±5.13) months, with a t value of 58.0 and a P value of 0.140, indicating no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). Both groups had no adverse reactions. See Table 2 for details.

4. Discussion

No significant differences were observed in age, gender, affected sites, or disease duration between the two groups. The Local Treatment Group received more local treatments on average than the Combined Release Group, and this difference was statistically significant.The Combined Release Group had shorter recovery times and fewer treatments than the Local Treatment Group, with statistically significant differences. There were no statistically significant differences in the number of relapses or Time to Relapse between the two groups. Both groups had no adverse reactions.

As far as we know, This study may be the first to use a retrospective cohort study method to investigate the relationship between quadriceps tension release and improvement of OSD. The results show that although the Local Treatment Group received more local treatment support than the Combined Release Group, the treatment duration and number of sessions in the Combined Release Group were significantly lower, indicating that releasing quadriceps tension significantly impacts OSD treatment. Hannah N Ladenhauf et al. also believe that quadriceps stretching is one of the strategies for preventing and treating OSD, but no statistical data analysis has been provided to support this.24 Cornelia Neuhaus et al. found that quadriceps stretching exercises significantly benefit OSD treatment, but they also noted the lack of high-quality research to support their findings.25 Few studies currently exist on alleviating quadriceps tension for treating OSD, highlighting the need for more large-scale, multicenter prospective clinical studies in the future to provide robust evidence.

This therapeutic effect is likely due to the link between quadriceps tension and OSD. Danielli R. Rodrigues and colleagues suggest that quadriceps tension and stiffness are clinical manifestations observed in patients with OSD.26 Research by Shota Enomoto and his team indicates that, under stretching conditions (knee flexion at 45° and 90°), the muscle stiffness of the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis is linked to the occurrence of OSD.27 Gildásio Lucas de Lucena et al. conducted a cross-sectional survey which suggests that rectus femoris muscle shortening is a major factor in Osgood-Schlatter syndrome among students. They found that 74.6% of the patients had this muscle shortening, indicating that the increased eccentric force of the knee extensor mechanism may contribute to the condition.19 These findings are consistent with the results of our research.

Some authors believe that before the fusion of the epiphysis, the blood circulation to the tibial tuberosity comes from the patellar ligament. Intense activities, such as running and jumping, can lead to strong and repeated contractions of the quadriceps muscle. This force is transmitted through the patellar ligament to the tibial tuberosity, causing repeated traction on this area.28 Repeated pulling damages the epiphysis and causes localized edema,29 which further disrupts blood circulation, obstructs blood supply, and leads to swelling, pain, aseptic inflammation, and even necrosis.30 Some studies indicate that excessive pulling of the patellar ligament on the bone protuberance can lead to rare avulsion fractures.5,31 Although many scholars support these findings, further basic research is needed to validate them.

The recurrence rates and time to relapse of the two groups are similar, and the statistical difference is not significant, which may be related to the insufficient sample size.

One advantage of this study is that it may be the first to use a retrospective cohort study method to explore the relationship between quadriceps tightness and OSD, indicating a possible link to the etiology of osteoarthritis. Furthermore, the study’s patient population includes physically active adolescents, and the cases data is sourced from a professional youth sports group, enhancing its representativeness. The limitations of this retrospective study include the involvement of various treatment protocols for the collected cases. Although the procedures were performed according to guidelines and instructions, potential confounding factors cannot be completely ruled out. Additionally, since this study includes cases from only one center and has a small data set, larger multicenter studies are needed to validate the findings.

5. Conclusion

Releasing tension in the quadriceps muscles can speed up the rehabilitation process for Osgood-Schlatter disease (OSD). This study highlights the importance of reducing quadriceps tension in the treatment of Osgood-Schlatter disease. It also suggests a possible connection between quadriceps tension and the cause of OSD. Nevertheless, additional basic research and large-scale multicenter studies are essential for further validation.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the participants for their voluntary participation, patience, and availability.

Corresponding author

Full name:Zhijun,Ding;

Phone number:+8615756279825;

E. mail:356585121@qq.com.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Hui,Pan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization.

Wei,Bai: Collect cases data,Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization.

Chang,Zhang:Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization.

Chao,Wang:Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization.

Liwei,Liu:Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization.

Shuxiang,Chen:Conceptualization, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization.

Zhijun,Ding:Methodology, Validation,Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization.

Competing interests

There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Ethical Committee of Jiangmen Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital Affiliated to Jinan University (Ethical Committee of Wuyi Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, Jiangmen City) ( Approval No. YJS[2025]-37).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.