Introduction

In 1972, the Title IX legislation led to a significant increase in high school sports participation among girls. From 1972 to 1978, participation grew by 600%.1 Afterwards, between 1973 and 2018, the percentage of high school sports participation by girls nearly doubled.2 While this has been a positive development for women’s involvement in sports, it has also led to an increase in sports-related injuries. This rise has prompted further research into injuries that female athletes are at higher risk for such as bone stress injuries, ACL injuries, and concussions.3 Of note, the incidence of ACL injuries is two to eight times more frequent than their male counterparts.4 Female athletes are more likely to sustain ACL injuries compared to their male counterparts. Various factors have been suggested to explain this disparity, including differences in female anatomy, the laxity of ligaments and muscles due to hormonal cycles, and differences in biomechanics.

The aim of this study is to quantitatively analyze literature on ACL injuries in women through a bibliometric analysis. This method allows for the identification of trends in publications, such as keyword occurrences, and authorship in which these studies are published. Through this analysis, we will gain an overview of current research on ACL injuries in women.

Methods

The data extraction method was replicated using established bibliometric analysis methodology.5 This included specific instruction on how to conduct a search study, how to remove duplicates, and how to upload PubMed results into VosViewer where the data was analyzed.

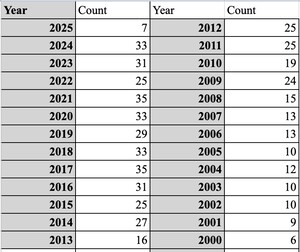

The data used in this analysis was extracted from PubMed on February 11th, 2025. The search strategy included an advanced search parameter as follows: (women or female[MeSH Terms]) AND (ACL injury[MeSH Terms])) NOT (male[MeSH Terms])) NOT (men[MeSH Terms])) NOT (man[MeSH Terms]). Additional filters selected were Full Text only, English only, Adults (19+ years old), publications from the years 2000-2025, and included original research, case studies, meta-analysis, systematic-reviews, and books and documents. The search result concluded with a total of 435 publications.

Once the results were downloaded, the data was analyzed with VosViewer. This platform studied the number of author co-occurrences, publication keyword co-occurrences, and keywords limited to MeSH only.

Results

Discussion

Publications

The number of articles on ACL injuries in females has generally increased over the years, likely due to the rising participation of women in sports and heightened attention to this topic. For example, from 1973 to 2018, the percentage of high school sports played by girls increased from 24.2% to 42.9% ([95% CI, 18.6–18.8], p < 0.0001),2 demonstrating almost a two-fold increase in participation. Factors contributing to this rise in female sports participation include sex equity initiatives and increased national funding for female athletes. Furthermore, the higher prevalence of ACL injuries may be attributed to differences in biomechanics, anatomical features, and the effects of the menstrual cycle on hormone levels.

Keyword Occurrence and MeSH Term Discussion

In the network cloud, several noteworthy terms emerged throughout the literature, including “risk factors,” “tibia,” “biomechanics,” and “quadriceps.” Some significant risk factors involve differences in female anatomy and biomechanics. It has been found that females tend to have a steeper posterior tibial slope.6 This anatomical feature increases strain on the ACL during abrupt movement changes, which can raise the risk of injury. Additionally, this paper discusses how smaller femur notches add strain to the ACL due to a reduced space between the femur and tibia.7

Another biomechanical difference observed in women is the increased activation of the quadriceps. Mechanically, the hamstrings act as agonists for the ACL by preventing anterior tibial translation, while the quadriceps act as antagonists, straining the ACL and causing increased anterior tibial translation.8 A study found that when women land, their legs are more rigid, causing the quadriceps to be more flexed. This suggests that the quadriceps are a major contributor to ACL injuries, as they lead to increased anterior tibial translation.9 In conclusion, the primary causes of ACL injuries related to biomechanics and anatomy are anterior tibial translation, which may be driven by a flexed quadriceps during landing or by smaller femoral notches in women.

Soccer and Basketball

Additional commonly used terms in the literature include “soccer” and “basketball.” At the collegiate level, the prevalence of ACL injuries in females is higher, with a higher incidence of injuries during competition as compared to practice sessions. The average ACL injury rate for female basketball players during competition was 0.68, compared to 0.10 during practice. For female soccer players, the rates were 1.12 injuries in games and 0.09 in practices. In contrast, male basketball players had an average of 0.14 injuries in games and 0.05 in practices, while male soccer players averaged 0.45 injuries in games and 0.06 in practices.10 Soccer and basketball are both considered contact sports, requiring abrupt movements, quick rotational changes, and jumping. These abrupt changes can cause an increase in ACL strain due to biomechanical or anatomical susceptibility. An additional risk factor in soccer is the type of playing surface. Studies have found that female athletes are more prone to ACL injuries on artificial turf compared to natural grass, whereas this difference was not significant for male athletes.11 The higher incidence of ACL injuries in these sports has led to an increase in prevention programs. Effective exercises include those focused on landing stabilization, as well as strengthening the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calves.12 These exercises have been shown to significantly reduce the risk of ACL injuries. Therefore, those training programs should be implemented at all levels of sports to continue to strengthen these muscles and prevent injury at any level.

Publications Authorship

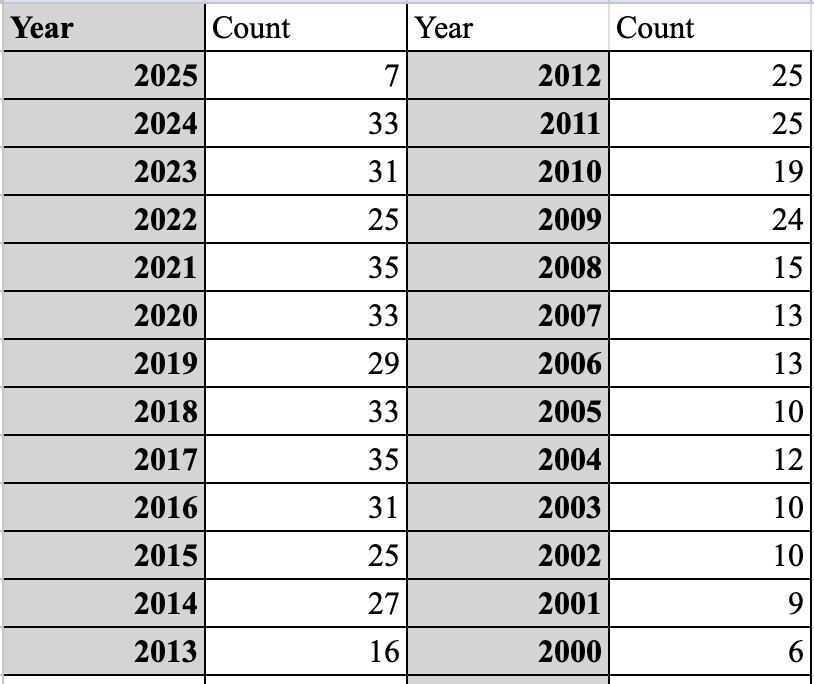

All of the authors listed in the publication image are affiliated with the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences and the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center.13 According to VosViewer, each author has contributed to 6-14 documents, and many have collaborated on numerous projects, as indicated by the linkages on the image.

Tron Krosshaug, affiliated with the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, has been involved in several papers as a project manager. During his PhD, he focused on joint motion analysis and has since worked extensively on injury mechanisms and risk factors for ACL injuries.14

Roald Bahr, MD, PhD, also affiliated with the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, has contributed to 14 documents on ACL injuries in females. He is currently working on projects related to athlete screening, injury prevention, and risk management for female football athletes.15

Grethe Myklebust, a physical therapist at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, completed her PhD in 2003, focusing on ACL injury prevention in handball and football. She also recently co-authored a paper on ACL prevention strategies with Kathrin Steffan.16

Kathrin Steffan, a researcher at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, completed her PhD in 2008. Her work focuses on epidemiology, injury prevention, para-athletes, and health monitoring.17

Agnethe Nilstad, a physical therapist and PhD, is affiliated with both the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center and the Division of Orthopedic Surgery at Oslo University Hospital. Her PhD dissertation addressed risk factors and injuries in elite female football players, emphasizing the importance of screening and prevention.18

Eirik Kristianslund, MD, PhD, specializes in biomechanics analysis. He has worked on projects studying knee biomechanics, including drop jumps, sidestep cutting, ACL injury motion patterns, and valgus knee movements.19

Limitations

The data used for this analysis was limited to PubMed and English-language-only studies were selected. This excluded additional publications that may have contributed data leading to an incomplete data collection process and potential gaps in the analysis.

Conclusion

There has been a steady increase in the number of ACL publications with the primary focus on understanding of the increased incidence in female athletes. This research has spurred initiatives to develop prevention programs targeting the primary mechanism of ACL injury—instability during anterior tibial translation. As discussed, this injury can be attributed to a smaller femoral notch compared to males, or biomechanical differences such as a landing with a flexed quadricep. Further research can be conducted to include other databases. Lastly, this research opens the door to look at the differences in female and male post-surgery ACL recoveries.