Introduction

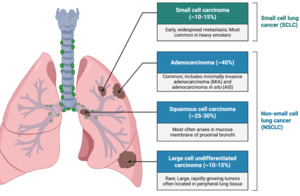

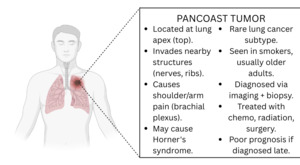

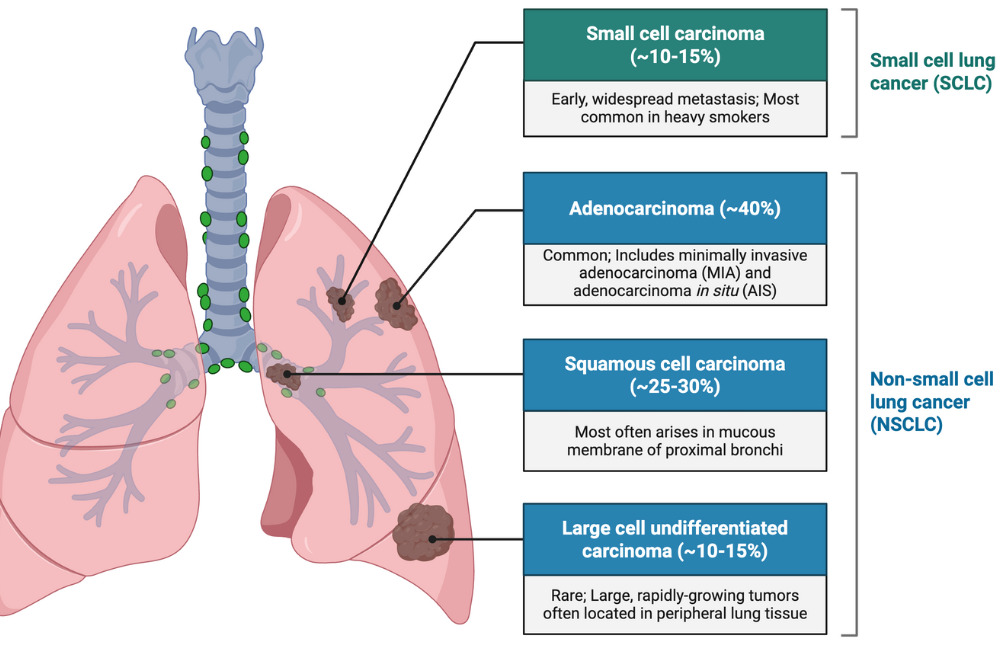

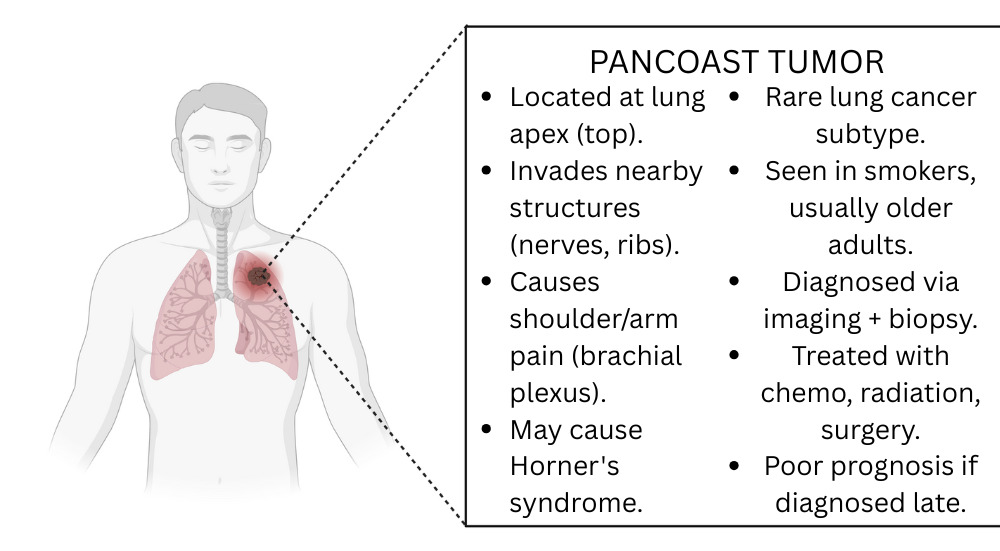

Pancoast tumors, or superior sulcus tumors, are a rare form of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) that arise in the apical region of the lung, and account for around 3–5% of all lung cancers.1,2 (Figure 1).

Pancoast tumors are separate from other pulmonary malignancies as they characteristically invade adjacent structures of the thoracic inlet such as the brachial plexus, subclavian vessels, ribs, vertebral bodies, and the sympathetic trunk.3 This specific anatomical alignment results in a characteristic clinical condition referred to as Pancoast-Tobias syndrome, which is characterized by severe pain in the shoulder and upper limb (often radiating along the ulnar pathway), Horner’s syndrome (composed of ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis), along with weakness or wasting of the hand muscles.4,5 (Figure 2)

The frequently deceptive characteristics of these symptoms present a significant challenge for diagnosis because pulmonary signs such as cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis are frequently absent, especially in the early stages, causing clinicians to first consider orthopedic or neurological diagnoses.1,6 Because of this, patients are often initially wrongly diagnosed with cervical disc disease, rotator cuff pathology, or frozen shoulder. This can often lead to long periods of inappropriate treatment before imaging reveals the true malignancy. In fact, neck pain is one of the most common initial complaints in Pancoast tumor patients yet is rarely recognized as a harbinger of apical lung cancer without a high index of suspicion.3,7,8 In this case report, the authors describe a case of a Pancoast tumor masquerading as neck pain and the timeline of diagnosis of the patient.

Case Presentation

The patient is a 71-year-old male who presented to the emergency department with complaints of chronic, persistent neck pain. He stated he had tried using over the counter pain medication for pain relief, but that there was little to no improvement of symptoms. Patient also reports sensations of right arm pain, numbness, tingling, weakness, and reduced grip in the right hand since the past 5 weeks. Patient mentions noticing a localized mass in the right axilla region. He denies any similar complaints involving the left upper extremity. Patient has a known history of smoking.

The patient’s vital signs were temperature 98°F, respiratory rate 18, blood pressure 134/86 mmHg, pulse 82, and oxygen saturation 94% on room air. Physical examination was unremarkable except for a palpable mass noted in the right axilla. No palpable masses were noted in the neck. Neurological examination revealed signs of radiculopathy in the right upper extremity.

MRI of the right shoulder revealed the mass in the patient’s axilla to be a focal protuberance of asymmetrical fat, suggestive of a non-encapsulated lipoma, as well as evidence of mild degenerative changes of the shoulder joint. CT lung screening showed findings most suggestive of a Pancoast tumour in the right lung apex with destruction of the right C7 and T1 vertebral bodies as well as the right first and second posterior ribs. A concurrent MRI of the cervical spine was conducted, the findings of which corroborated the results of the CT lung screening. MRI cervical spine demonstrated a locally invasive mass in the apex of the right lung, along with erosion of the first and second ribs, and involvement of the right brachial plexus. There was also evidence of metastasis at C6–T2 level, with paravertebral, neural, and transverse foraminal involvement predominantly on the right. Patient was referred to oncology and started on treatment.

One month later, the patient returned to the ED, with onset of a new symptom, shortness of breath. An X-ray chest was ordered and compared to previous CT lung; no significant changes in the right upper lobe mass were found, with no new focal consolidation. A PET CT scan was conducted, confirming a 4.9 cm hypermetabolic Pancoast tumor involving the right lung apex with contiguous spread of the tumor directly involving the right first and second ribs. There was also evidence of lytic osseous metastases involving the C6 – T2 vertebra with tumor involving the right paraspinal musculature from C7 – T2 and possible tumor involvement of the spinal canal from C7 - T2 level. The PET scan also revealed metastatic right suprahilar and right paratracheal adenopathy and a definitive osseous metastasis involving the T11 spinous process.

A CT guided biopsy of destructive bone tumor of the posterior elements of T1 was conducted to ascertain histopathological confirmation of metastasis of the tumor. The biopsy showed metastatic carcinoma cells infiltrating fragments of bone. Immunohistochemical stains were performed to evaluate for site of origin and further characterization of the carcinoma cells. The carcinoma cells were positive for p40 immunostain, suggestive of squamous cell carcinoma. A p16 immunostain was also carried out to test for whether the primary site of tumor originated in the head and neck, the results of which were determined to be negative. The timeline of the patient’s course is summarized in Figure 3.

Discussion

Patients with Pancoast tumors often present with symptoms that are different from typical lung cancers due to their locally invasive nature and unique location.3 The most common early symptom is shoulder pain. This results from tumor extension into the parietal pleura, upper ribs, vertebral bodies, or brachial plexus. Neurological manifestations such as numbness, tingling, or weakness in the ipsilateral arm may occur as the tumor follows its course.9 This may lead to a misdiagnosis of musculoskeletal or cervical spine disorders as differential diagnoses in patients with upper extremity neurologic symptoms include cervical radiculopathy, brachial plexopathy, thoracic outlet syndrome, and rotator cuff pathology.10,11

Invasion of the sympathetic chain can lead to Horner’s syndrome which occurs in a significant percentage of patients affected by Pancoast tumors.12 Due to the tumor’s peripheral location and initial absence of respiratory symptoms, diagnosis is frequently delayed, allowing for the malignancy to progress and metastasize. This makes early recognition critical to avoid complications due to the cancer’s progression.10,13,14

This case deviated from the classic Pancoast tumor presentation. Rather than vague or localized discomfort, the patient exhibited rapid-onset neuromuscular deficits affecting the entire right upper limb, including motor weakness and muscle atrophy, suggesting extensive brachial plexus involvement. This initially presented as chronic neck pain, due to which a Pancoast tumor diagnosis was delayed until the development of more conventionally described symptoms such as shoulder and arm pain. Also, typical pulmonary symptoms such as cough or dyspnea were absent, and initial radiographic findings failed to highlight a prominent apical mass. This atypical presentation delayed suspicion for a pulmonary malignancy. Rather, given the seemingly inexplicable presentation of chronic neck pain, the doctors were led to the assumption of primary cervical spine pathology. This shows the importance of including Pancoast tumor in the differential diagnosis of upper extremity neurologic compromise, even in the absence of classic respiratory signs.

Pancoast tumors are likely to be suspected in individuals with the most major risk factor being a significant smoking history, and others being male sex, and age in the sixth decade.9 While initial evaluation may include standard radiographs, chest X-rays often fail to detect tumors; in such cases, contrast-enhanced CT can confirm the presence of a mass, and an MRI is particularly valuable for assessing soft tissue invasion, as well as brachial plexus or spinal involvement.15 When upper extremity symptoms persist and are not explained by cervical spine imaging, targeted MRI of the thoracic inlet or brachial plexus should be considered to avoid diagnostic delays, as illustrated in this case.

Several other case reports similarly highlight atypical presentations that contributed to delayed diagnoses. For example, multiple cases mimicked cervical radiculopathy and musculoskeletal conditions such as frozen shoulder and cervical spondylosis, with patients presenting primarily with neck, shoulder, or arm pain without respiratory symptoms.1 One report by M M Vargo and K M Flood described a patient misdiagnosed and treated for cervical discopathy for over a year before imaging revealed an apical lung mass with rib destruction, ultimately confirmed as bronchogenic adenocarcinoma.16 Another case by Chu and Lai et al involved a chiropractor identifying a Pancoast tumor in a patient with refractory neck pain despite normal cervical MRI findings; thoracic imaging eventually revealed the diagnosis. This report also reviewed six additional cases of undiagnosed Pancoast tumors presenting in chiropractic settings, showing how symptoms of Pancoast tumor frequently present as musculoskeletal conditions.17 Additionally, another rare case by Slack and Shannon described Pancoast syndrome secondary to metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma showing that it’s important to consider non-pulmonary primaries in patients with known malignancy and new-onset upper extremity neurological deficits.18 This was highlighted in our case as we were to rule out a non-pulmonary primary that was metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (due to the patient’s chronic neck pain) using a p16 immunostain. Such atypical cases emphasize a necessity for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for Pancoast tumors when symptoms persist despite standard musculoskeletal treatment.

Traditionally, management of Pancoast tumors includes neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by en bloc surgical resection.19,20 This is because its location and nearness to important structures could pose challenges for surgery.21 The standard treatment today typically includes trimodality therapy with the addition of platinum-based chemotherapy regimens.22 In this case, the involvement of the right vertebral artery and an epidural tumor could limit surgical options and reinforces the importance of early detection prior to invasion of critical structures.

Prognosis in advanced cases such as this one with extension of tumor into the base of neck, vertebral bodies, and great vessels remains poor, emphasizing the need for timely diagnosis.23–26 Ultimately, this case serves as a clinical reminder to pursue thorough evaluation when atypical neuromuscular presentations arise, even in the absence of pulmonary complaints.

Conclusion

Pancoast tumors are a rare type of non-small cell lung carcinoma that originate in the lung apex. They characteristically invade nearby structures such as the brachial plexus and sympathetic chain, which typically causes the common symptoms of shoulder pain and arm weakness. This patient, a 71-year-old male with a history of smoking, presented with inexplicable chronic neck pain and neuromuscular deficits of the upper limb. This led to a delayed diagnosis due to suspicion of primary cervical spine pathology, due to which advanced imaging and immunohistochemistry was required to rule out alternative etiologies and confirm the diagnosis of Pancoast tumor. It is important for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for Pancoast tumors when evaluating persistent neuromuscular symptoms of the upper limbs, including chronic neck pain, even in the absence of pulmonary signs and symptoms.