1. Introduction

Isolated radial head dislocation may be congenital or traumatic. The congenital form can occur alone or in association with syndromes such as skeletal dysplasia, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, or trisomy 8 mosaicism. In children, traumatic isolated radial head dislocation may be seen with Monteggia fracture–dislocations or elbow dislocations.1,2 By 2004, only about 81 cases had been reported in the literature. Because of its rarity and the sometimes subtle clinical and radiographic findings, this injury is easily overlooked. Delayed or missed diagnosis can lead to serious sequelae, including chronic pain, restricted motion, elbow deformity, secondary osteoarthritis, and impaired elbow function.1,2

Stability of the humeroradial joint depends primarily on the integrity of the annular ligament and the morphological congruence of the articular surfaces. Therefore, restoring the radial head to its anatomic position is essential to ensure normal elbow function. In delayed presentations, closed reduction often fails, and open reduction with annular ligament reconstruction is the treatment of choice.1,3 We report a late-diagnosed case of isolated radial head dislocation, describe management and outcomes, and provide a brief literature review.

2. Case presentation

2.1. Patient information

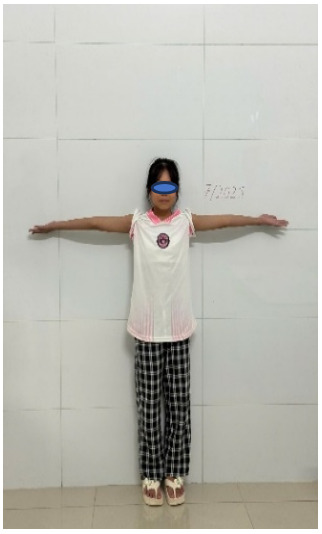

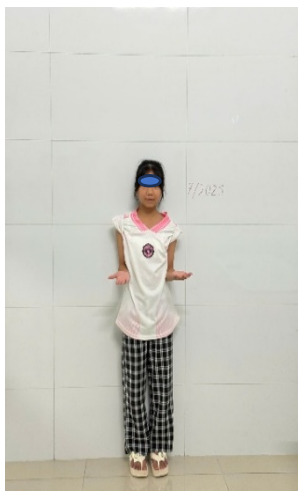

A 7-year-old girl was brought to a local emergency department after falling while playing in a park, landing on her outstretched left hand with the arm abducted. She had pain and swelling of the left elbow with limited motion. She was diagnosed with a soft-tissue injury and immobilized in a plaster splint for two weeks. Three weeks after the injury, she was referred to Thai Binh University Hospital because of persistent elbow pain and marked limitation of motion in the left elbow (Figure 1).

2.2. Clinical findings

At admission the left elbow showed mild lateral swelling with intact skin. There was tenderness over the anterolateral aspect of the elbow. Forearm pronation and supination were painful and limited. Elbow flexion extension was also limited at the terminal range. There were no signs of joint effusion or nerve injury. The child had no prior history of dislocation or joint laxity.

Timeline

-

Day 0: Injury occurred from fall on outstretched hand.

-

Days 0-14: Initial diagnosis as soft-tissue injury; immobilized in plaster splint at local facility.

-

Week 3: Referral to Thai Binh University Hospital; clinical examination and radiographs performed.

-

Week 3 (surgery day): Closed reduction attempted under general anesthesia; failed, proceeded to open reduction and annular ligament reconstruction.

-

Week 6: Kirschner wire removed; splint removed; active exercises begun.

-

Month 3: Improved range of motion; participation in light activities.

-

Year 1: Near-normal activities resumed; 10° pronation limitation.

-

Year 5: Near-complete recovery; no recurrence or complications.

2.3. Diagnostic assessment

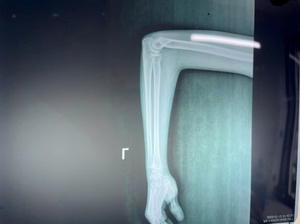

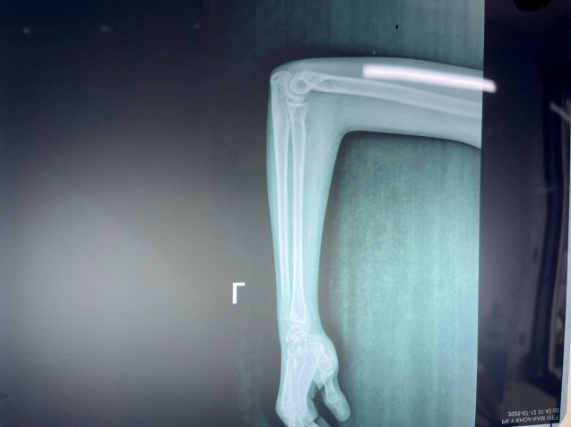

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the left elbow showed a complete anterior dislocation of the radial head relative to the humeral capitellum. The longitudinal axis line of the radius did not pass through the capitellum. No fractures of the radius or ulna were detected, and there was no ulnar bowing. The distal radioulnar joint was preserved. Based on imaging and clinical findings, the McFarland and the Mardem-Bey & Ger criteria for congenital radial head dislocation were not met (Table 1).3

2.4. Therapeutic intervention

Closed reduction under general anesthesia failed as expected, so open reduction was performed.

-

Surgery: Under general anesthesia, the elbow was approached through a posterolateral Boyd incision. Intraoperatively, the annular ligament was completely ruptured, fibrosed, and interposed in the joint, preventing reduction. Scar tissue around the humeroradial and proximal radioulnar joints was fully released. After cleaning the articular surfaces, the radial head was reduced to its anatomic position.

-

Annular ligament reconstruction: A modified Bell–Tawse technique was used. A 6–7 cm strip of triceps tendon, left attached to the olecranon, was passed around the radial neck and sutured to create a new annular ligament.

-

Fixation: Temporary stabilization was achieved with a 2.0-mm Kirschner wire passed from the lateral humeral condyle into the axis of the radial head with the elbow at 90° flexion and the forearm fully pronated. Postoperatively, the limb was immobilized in a long-arm plaster splint.

3. Management and Outcomes

Postoperative check radiographs showed the radial head restored to anatomic position with a stable humeroradial joint (Figure 3). The postoperative course was stable; swelling was mild and pain was moderate, controlled with simple analgesics. The Kirschner wire was removed at 3 weeks without infection or displacement, and the long-arm plaster splint was removed at 6 weeks, at which time the child began supervised active exercises with a rehabilitation specialist.

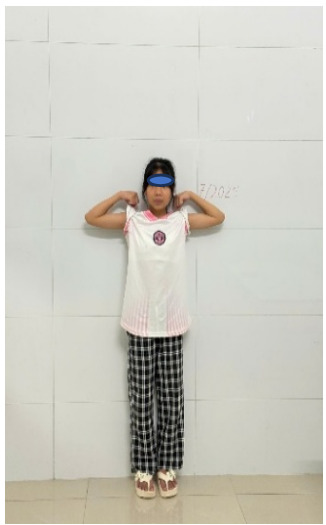

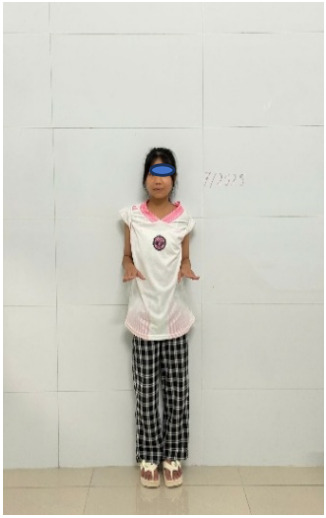

At 6 weeks postoperatively, range of motion had improved markedly compared with preoperative status: elbow flexion 115° (improved from a terminal limitation preoperatively), extension lacked 5° of full range, and pronation-supination measured 0°-25°. Acute pain had resolved and the child could perform light daily activities such as grasping objects. There was no recurrence of humeroradial dislocation, and the incision healed well. By 3 months, ROM continued to improve to 130° of flexion, full extension, and 0°-50° of pronation–supination, allowing participation in light play without assistance.

At 1 year of scheduled follow-up, the patient had resumed nearly all normal activities, including self-care and non-contact sports, with only a 10° terminal limitation of forearm pronation compared with the uninjured side. There was no recurrent dislocation, chronic pain, elbow deformity, or nerve palsy. Radiographs showed an anatomically aligned radiocapitellar line, confirming the success of annular ligament reconstruction.

4. Discussion

Traumatic isolated radial head dislocation is uncommon and is easily missed or misdiagnosed as an elbow soft-tissue injury. Missed diagnosis occurs because clinical symptoms are nonspecific and radiographic signs may be subtle. Careful clinical examination and standard radiographs in appropriate views are required when suspected. Meticulous assessment of the radiocapitellar line in pediatric elbow trauma is key to detecting isolated radial head dislocation.1,3

The usual mechanism is a fall on the outstretched hand with the elbow extended and the forearm in excessive pronation. This force ruptures the annular ligament and the anterior capsule, producing anterior radial head dislocation. Some studies consider this a variant of Monteggia type I, in which the ulna sustains only micro-bowing rather than a complete fracture. However, many reported cases show no ulnar bowing, indicating that dislocation can occur solely from annular ligament rupture.2,4

For early presentations within one week of injury, closed reduction and cast immobilization are preferred. Closed reduction may fail because interposed soft tissues, such as a torn capsule or annular ligament, block reduction. In delayed cases (often after three weeks), as in our patient, closed reduction almost always fails due to fibrosis and contracture of soft tissues. Open reduction is then required to restore anatomy and prevent long-term complications.1,2 Annular ligament reconstruction is important to ensure postoperative stability and prevent redislocation. Various techniques exist; using a triceps tendon strip (Bell–Tawse technique) as we did is a good option because the autologous graft is available, robust, and in the operative field. At 5-year follow-up our patient had excellent function, normal humeroradial alignment on radiographs, no redislocation, and no complications.

Management of late-presenting symptomatic cases in children remains controversial. Some authors, notably Blount, cautioned that surgery may yield worse function than natural history. Vinz also reported that surgical results are not consistently good. In contrast, many reports, including ours and that of Ayouba et al., show very good outcomes after open reduction and ligament reconstruction. With proper indications and surgical technique, good results can be achieved.2,4

5. Conclusion

Traumatic isolated radial head dislocation in children is rare and easily missed. Consider this diagnosis in elbow trauma, perform careful clinical examination, and analyze radiographs thoroughly to enable early detection. Timely diagnosis and treatment lead to good outcomes and prevent complications and sequelae. In delayed cases, open reduction with stabilization of the humeroradial joint and annular ligament reconstruction is effective and can restore full function.

ILLUSTRATIVE IMAGES DEMONSTRATING THE FINDINGS AT 5-YEAR FOLLOW-UP

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for the publication of this case report and accompanying images, in accordance with ethical standards.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.