1. Introduction

Primary cardiac tumors are extremely rare, with reported rates in autopsy studies ranging from just 0.001% to 0.03%, and the majority are benign.1,2 Among these, cardiac osteosarcoma stands out as one of the rarest and most aggressive forms. The first known case was reported in 1957 at Kingston General Hospital in Canada.3 Histologically, it’s defined by the presence of malignant cells producing an osteoid matrix.4 Up until 2016, only 53 cases had been documented in the literature, most commonly arising in the left atrium and typically affecting adults in midlife.2,5 Patients often present with vague cardiovascular symptoms, which can delay diagnosis, and tend to carry a poor prognosis due to high rates of recurrence and metastasis. This review will summarize current knowledge about cardiac osteosarcoma, including its presentation, treatment options, and key considerations for surgery and anesthesia.

2. Epidemiology

As the name implies, osteosarcoma is a malignant tumor that originates in bone, most commonly affecting long bones such as the femur or humerus.6 Though rare overall, it accounts for about 0.2% of all malignant tumors. When it occurs in the heart, primary cardiac osteosarcoma represents the rarest subtype of cardiac sarcomas; a malignant mesenchymal tumor characterized by osteoblastic differentiation.7 Among all cardiac sarcomas, osteosarcomas make up roughly 3–9% of cases.8 Due to its exceptionally low incidence, the World Health Organization excluded cardiac osteosarcoma from its 2004 classification of cardiac sarcomas.9 Since then, these tumors have more often been described as “undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas with prominent osteosarcomatous differentiation.”

Cardiac sarcomas can occur at any age and do not appear to favor one sex over the other.9 Reported cases of cardiac osteosarcoma span a wide age range, from 14 to 77 years, with the average age at diagnosis falling between 35 and 45.1,5 While some studies have noted a slight female predominance, this is likely due to limited sample sizes rather than a true biological trend. To date, no specific genetic, environmental, or geographic risk factors have been identified. However, previous exposure to therapeutic radiation has been linked to an increased risk of primary cardiac sarcomas, though this association is more consistently observed in angiosarcomas than in osteosarcomas.7

3. Reported Cases and Outcomes

Although cardiac osteosarcoma is generally associated with a poor prognosis, outcomes can vary significantly based on factors such as tumor location, histologic grade, treatment approach, and recurrence patterns. In one case, a 44-year-old woman presented with a left atrial mass causing severe mitral valve obstruction.1 She underwent complete surgical resection followed by six cycles of doxorubicin and cisplatin. Remarkably, she remained asymptomatic with no evidence of recurrence during 10 years of follow-up. This far surpassed the reported 5-year survival rate of 33.5% for this disease. Notably, the disease-free survival rate remains considerably lower, at just 6.3%.

In contrast, a 54-year-old woman with a high-grade biatrial tumor and vertebral metastases experienced rapid disease progression within nine months, despite undergoing chemotherapy.2 Additional treatments with cyclophosphamide and topotecan produced a partial response, but durable disease control was not achieved, highlighting the limitations of current therapies in advanced cases.

A case reported in Turkey documented a 40-year old woman who experienced dyspnea, weakness, and syncopal attacks was found to have a 3.5 x 3 cm mass in the left atrium on TTE.9 Further studies using CT demonstrated a calcified core, but even so, a presumptive diagnosis of cardiac myxoma was made. Upon resection of the tumor, histologic findings of osteoid and fibroblastic cells were identified. The fully excised mass measured 8x4x4cm, and the removal of the interatrial septum was necessary. The authors of this paper suggest the etiology of primary cardiac osteosarcoma may be metaplasia of the fibrous trigone, which arises from fibroblasts.

To highlight the various ways cardiac osteosarcoma may present clinically, a 29-year old male was hospitalized with a mild fever, distended neck veins, and bilateral pitting edema.10 Imaging showed cardiomegaly and hepatomegaly, as well as a round lung lesion. He was initially diagnosed with pericarditis and was given a course of diuretics with some improvement. Notably, the patient had several painless movable nodules in both legs after resolution of the lower extremity edema. Review of plain films indicates the lesion originally thought to be within the lung may in fact be within the heart. Upon biopsy of the nodules in his legs, he was diagnosed with undifferentiated sarcoma. The patient died four days later. The autopsy showed extensive cardiac infiltration by the tumor as it obliterated the interatrial septum and extended into the tricuspid valve, superior vena cava, inferior vena cava, and mitral valve. The pathology report showed a variety of bony, cartilaginous, and malignant osteoblastic tissue.

Another case can be found in a 42-year-old woman who presented with chest tightness and dyspnea.11 The mass was further evaluated using echocardiography and CT, revealing a mass measuring approximately 5 x 3 cm adhering to the posterior atrium via a pedicle. Again, cardiac myxoma was the presumptive initial diagnosis. Tumor cells were found to be pleomorphic with osteoid lattice and cartilaginous differentiation. Osteoclastic-like cells were also present. The patient was treated surgically without chemotherapy or radiation, and lived without recurrence at 20 months post-op.

A similar case involved a 41-year-old man who developed recurrent biatrial tumors with extensive bone metastases, including spinal cord compression and an unusual rectal metastasis.12 Despite undergoing multiple surgical resections, radiation therapy, and multi-agent chemotherapy, he survived 61 months post-diagnosis. This represented one of the longest reported survival durations for cardiac osteosarcoma.

In an extensively well documented case, a 64-year-old male was referred to the Mayo Clinic after an echocardiography report elsewhere showed the presence of a large left ventricular density.13 Surprisingly, he was asymptomatic upon presentation. The physical exam and routine laboratory results were unremarkable. TTE and CT demonstrated a heavily calcified left ventricular mass measuring approximately 3 x 2 cm that did not impede normal cardiac function. A follow up three months later showed no change in mass size, and the patient decided not to pursue surgery. 4 years later, the patient presented to another hospital with unstable angina and was found to have severe multivessel coronary disease which he underwent uncomplicated coronary artery bypass grafting. The surgeon noted a large posterior myocardial and endocardial calcification, but no specimen was obtained. The remainder of his hospitalization was uneventful, but he was readmitted 1 month later for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. He made a full recovery with adequate treatment and remained asymptomatic for 1 year. The patient then began experiencing monomorphic ventricular tachycardia intermittently and was started on antiarrhythmic medications. Repeat CT scans several months later showed the left ventricular mass has enlarged to 6.5 x 2 cm and a new 1.5 cm left lower lung nodule. The patient underwent surgery for the excision of the lung nodule and was diagnosed with osteosarcoma with pulmonary metastasis. Workup for primary osteosarcoma elsewhere was negative, thus it was diagnosed as primary cardiac osteosarcoma. He received a systemic chemotherapy cocktail consisting of ifosfamide, etoposide, mesna, mitomycin, doxorubicin, and cisplatin. Imaging after chemotherapy showed no change in cardiac tumor size. Almost 1 year later, the patient had a cardiac arrest. Electrocardiogram showed inferior wall ST elevation and he was resuscitated in the emergency department. The patient developed an infection followed by multiorgan failure and died. At the time of death, the left ventricular mass was measured at 6.8 x 6 cm. It demonstrated typical findings of osteosarcoma in histopathologic studies.

One of the youngest documented cases of primary osteosarcoma occurred in a previously healthy 14-year-old male who presented with a three-week history of fatigue, lightheadedness, pallor, syncope, and vomiting.14 His initial evaluation revealed a concurrent upper respiratory infection, but laboratory studies and echocardiography were unremarkable. He was rehydrated in the emergency department and discharged, yet his symptoms persisted. Over the following week, additional outpatient testing was unrevealing. Upon readmission, he reported abdominal tenderness, bloating, and a 10-pound weight gain in one week. Computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated a mass within the inferior vena cava extending from the caval bifurcation into the right atrium. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a mass occupying approximately 90% of the right atrial cavity, and transesophageal echocardiography confirmed an immobile, heterogeneous mass measuring 3 × 2 cm that partially obstructed tricuspid inflow. The patient subsequently underwent surgical debulking, during which the tumor was found to invade both right pulmonary veins, the atrial and ventricular septum, and the inferior vena cava with near-occlusion of venous return. Histopathology identified a large-cell calcified sarcoma characterized by calcified tumor cells with cartilage and bone formation and patchy areas of necrosis. The unusual right-sided location of this cardiac osteosarcoma likely contributed to its extensive local invasion.

More recently, a 46-year-old male presented with palpitations and dyspnea and was found to have a mass within the left atrium.15 Transthoracic echocardiography initially identified the lesion, which was further characterized by computed tomography as a 4 × 5 cm mass occupying most of the left atrial cavity, with extension into the mitral valve and pulmonary veins. The patient underwent surgical resection, and biopsy confirmed primary cardiac osteosarcoma. Although the tumor was successfully removed, follow-up imaging at six months revealed atrial ossification concerning for recurrence. The patient subsequently underwent heart transplantation in an effort to achieve definitive cure. However, seven months post-transplant, imaging demonstrated a 15 × 8 cm anterior mediastinal mass with heterogeneous enhancement. Further evaluation with CT and MRI revealed extensive metastatic disease, which had not been present on prior studies.

4. Risk Factors

Due to the extreme rarity of primary cardiac osteosarcoma, its underlying causes and predisposing factors remain poorly understood. To date, no consistent links have been established with genetic mutations, familial cancer syndromes, or geographic distribution.1,5 Although some types of cardiac sarcomas, most notably angiosarcomas, have been associated with prior exposure to ionizing radiation, this connection is less clearly defined in the context of cardiac osteosarcoma.7

Some researchers believe one possible etiology may be a result of previous tissue insult. In a case series by Sordillo et al, it is noted that out of 48 cases of extraosseus osteosarcoma, 13% had a history of trauma at the site of the primary tumor.16 One patient reportedly used a vibrating exercise belt on her buttocks for years prior to developing osteosarcoma in the area about half a decade later. Another patient had an automobile accident injury to her hip and developed chronic pain for 7 years before being diagnosed with extraosseous osteosarcoma at the injury site. In a separate case report, a 29-year old male developed osteosarcoma at the site of a previous intramuscular penicillin injection.17

Whether such associations are causal or merely coincidental remains uncertain and warrants further investigation.

5. Clinical Presentation and Physiology

Cardiac osteosarcomas, like other primary cardiac tumors, can significantly impair cardiac function. Due to their typical location and the higher prevalence of atrial myxomas, these tumors are often initially misdiagnosed as myxomas.1,7 However, imaging studies can help differentiate the two: cardiac osteosarcomas usually appear as broad-based, heterogeneous masses that may contain areas of calcification. In contrast, myxomas are typically gelatinous in texture and attached to the atrial septum via a narrow stalk.1

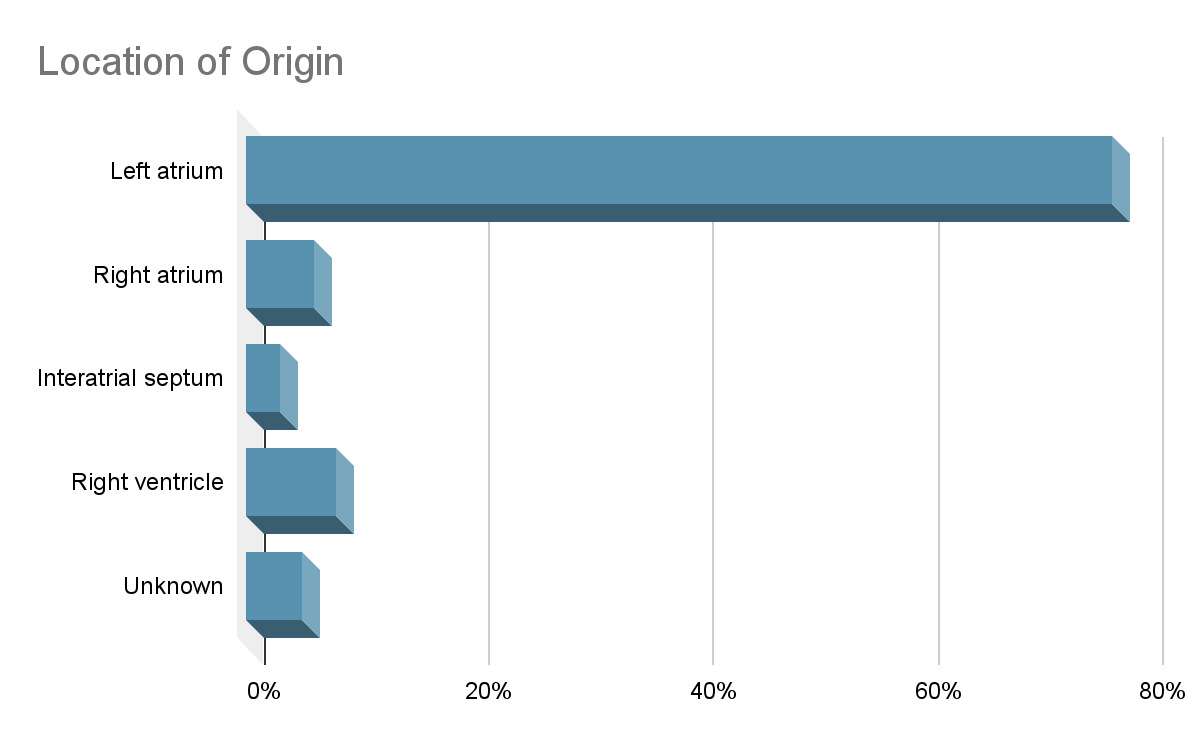

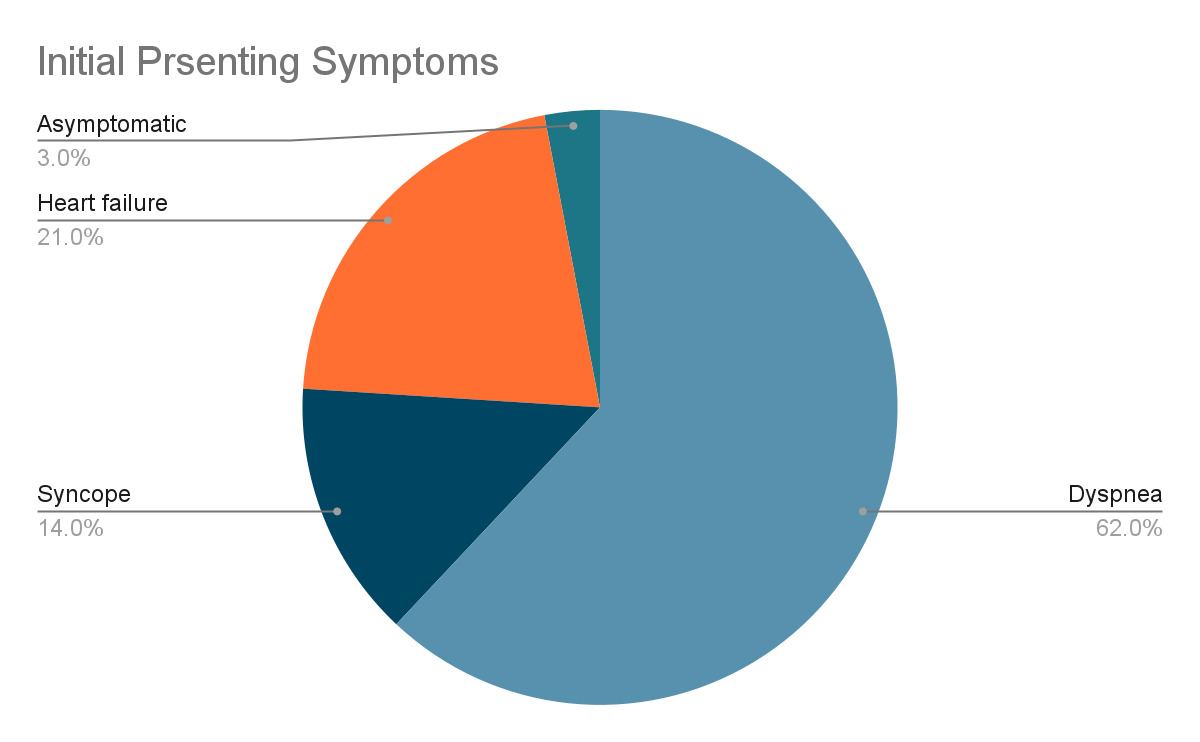

The functional impact of cardiac osteosarcomas depends largely on its size and location. These tumors most commonly arise in the left atrium, unlike metastatic osteosarcomas, which tend to involve the right atrium.18,19 Cardiac osteosarcomas are highly invasive, often infiltrating the myocardium, valves, and surrounding structures. When the mitral valve is involved, the tumor can obstruct blood flow into the left ventricle, creating a functional obstruction that clinically mimics mitral stenosis.1 Patients may present with symptoms such as dyspnea, syncope, fatigue, and hemoptysis. Prolonged obstruction may lead to signs of congestive heart failure, including pulmonary and peripheral edema, as well as secondary findings like splenomegaly and portal venous congestion.18

Intramural tumor extension can interfere with the cardiac conduction system, increasing the risk of cardiac arrhythmias.20 Other clinical manifestations may result from embolization, direct invasion, or compression of surrounding structures, leading to neurological deficits, palpitations, abdominal pain, or even claudication.

Cardiac sarcomas may also invade the pericardium, resulting in constrictive pericarditis or cardiac tamponade.18 In some cases, malignant pericardial effusion is the first clinical sign of a cardiac sarcoma.21 Patients with pericardial involvement may present with dyspnea, chest pain, and tachycardia. On physical exam, findings such as Kussmaul’s sign, Beck’s triad, pulsus paradoxus, or electrical alternans may be present, depending on the extent and nature of pericardial involvement.

Additionally, coronary artery invasion may occur and present with symptoms that mimic coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndromes. Patients reporting chest pain, angina, or radiation to the arm or jaw should undergo an ECG and may require coronary angiography for further evaluation.18

Signs and symptoms may overlap or occur concurrently depending on the structures affected. Initial presentation can be vague but is often recurrent after medical therapy. Dyspnea is often a result of pulmonary edema due to blockage of the outflow tracts causing congestion. Long term blockage may lead to congestive heart failure, which can also present as dyspnea, orthopnea, and peripheral edema.

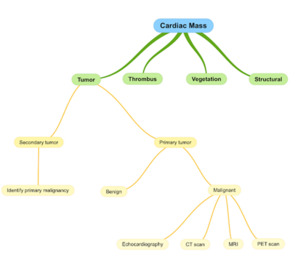

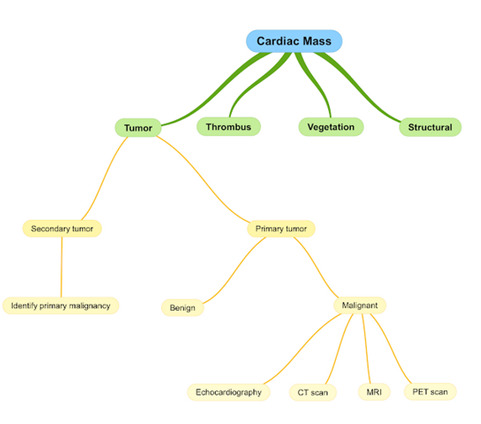

6. Diagnosis and Management

While histopathological examination is required for a definitive diagnosis, modern imaging modalities play a crucial role in the initial detection and management of cardiac osteosarcoma.22 Most cardiac sarcomas are first identified using transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) providing enhanced visualization of tumor characteristics and attachments (18,7). Multimodal imaging, including CT and MRI, further aids in assessing the tumor’s size, morphology, and location.19 Calcification, a common feature of cardiac osteosarcoma, is most clearly visualized on CT.19,22

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning may also be employed for staging, helping to identify potential metastases or additional lesions.

Histologically, osteoblastic, chondroblastic, and fibroblast lineage cells are universally found in primary cardiac osteosarcomas.5 These are also the most common subtypes of skeletal osteosarcoma. In most cases, the tumor is composed of more than one subtype and several differentiations along with neoplastic bone can be seen.

The standard of care for all cardiac sarcoma without metastasis is surgical resection followed by chemotherapy, with or without radiation.18,23 The goal, as with any malignancy, is to achieve negative surgical margins, but due to the highly invasive nature of cardiac sarcomas, it is impossible in most cases.23,24

The most common surgical technique is median sternotomy with cardiopulmonary bypass and resection of involved cardiac structures.1,18 Other surgical techniques include a minimally invasive approach via thoracotomy or the auto transplantation approach which requires removal of the entire heart from the chest cavity and the majority of the operation completed in the back table on the diseased heart.25 The operating surgeon must balance the risk of disease recurrence with the structural integrity of the heart. The infiltrative nature of cardiac sarcomas often requires radical resection and reconstruction of the heart. In one case, extensive resection of both atria as well as a pneumonectomy was required to remove the tumor.26

The advantage of surgery is immediate palliative relief of obstruction, potential to prolong life by complete removal of tumor, and to obtain a specimen for histopathology. However, it is not without significant risks. Surgical resection carries similar risks to any cardiac surgery, such as bleeding, coagulopathy, arrhythmia, damage to cardiac and surrounding structures, and death.27

Following surgery, systemic chemotherapy is typically employed with the goal of extending survival. Although there is no universal consensus on its efficacy in cardiac osteosarcoma specifically, the aggressive nature of cardiac sarcomas generally warrants adjuvant therapy, even in cases with negative margins.18 Agents commonly used for extracardiac osteosarcoma, such as doxorubicin, ifosfamide, cisplatin, methotrexate, gemcitabine, and taxanes, are often utilized, given the lack of cardiac-specific treatment protocols.1,2,18 Despite limited data, adjuvant chemotherapy has been associated with improved outcomes. One study reported an increase in median survival from 11 to 26 months in patients who received chemotherapy after surgical resection.5

The role of postoperative radiotherapy remains more controversial. Cardiac tissue is highly sensitive to radiation, and exposure can result in serious complications such as cardiomyopathy, pericarditis, and valvular dysfunction.28,29 Nonetheless, radiotherapy may offer therapeutic value in select cases. For instance, one patient with a high-grade unresectable cardiac sarcoma was treated with iododeoxyuridine and hyperfractionated radiotherapy, achieving complete remission with no recurrence over a five-year follow-up period.30 While the patient experienced some degree of cardiac injury, including right atrial dilation, mild valvular regurgitation, and recurrent pleural effusions, none of these complications revealed evidence of residual or recurrent malignancy.

7. Conclusion

Cardiac osteosarcoma is among the rarest and most aggressive forms of cardiac sarcoma, carrying one of the poorest prognoses. While most cases are diagnosed in middle adulthood, occurrences have been documented across a wide age range. Clinical presentation often mimics congestive heart failure due to impaired forward cardiac output, though symptoms can also reflect valvular or coronary involvement depending on the tumor’s location and pattern of invasion.

Diagnosis remains challenging due to the tumor’s rarity and nonspecific presentation, and treatment is equally complex. Surgical resection is the cornerstone of therapy for non-metastatic disease; however, extensive local invasion frequently limits the feasibility of complete resection. When surgery is possible, it should be followed by adjuvant therapy. Chemotherapy is generally recommended postoperatively, although care must be taken to minimize additional cardiac damage. Current chemotherapy regimens are extrapolated from protocols used in extracardiac osteosarcoma, as there is insufficient data to establish cardiac-specific treatment guidelines.