Introduction

The thumb contributes over 40% of total hand function,1 with the trapeziometacarpal (TMC) joint being considered the most important joint in thumb structure.2,3 The TMC joint has a special construction featuring dual saddle-shaped articular surfaces, stabilized by a complex ligamentous network for the wide arc of motion necessary for flexion-extension, abduction-adduction, and opposition.4–6 The stability of this highly mobile joint depends primarily on its ligamentous support system, with instability leading to significant functional impairment and disability.7 The TMC joint instability can result from traumatic injury or degenerative conditions, with osteoarthritis affecting up to 15% of adults over 30 years of age and showing a 10:1 female predominance.8,9 In developing regions with prevalent motorcycle usage, traumatic TMC dislocations occur with increased frequency due to specific injury mechanisms involving handlebar impact between the first and second metacarpals.7 These injuries significantly impair thumb function and overall hand capability, necessitating effective surgical intervention.

Five ligaments comprising three distinct systems maintain TMC joint stability: the volar system (anterior oblique ligament), the dorsal system (dorsal radial ligament, dorsal central ligament, posterior oblique ligament), and the ulnar collateral ligament.2,5,8 Understanding this complex anatomy has evolved considerably over recent decades, fundamentally altering surgical approaches to reconstruction.8

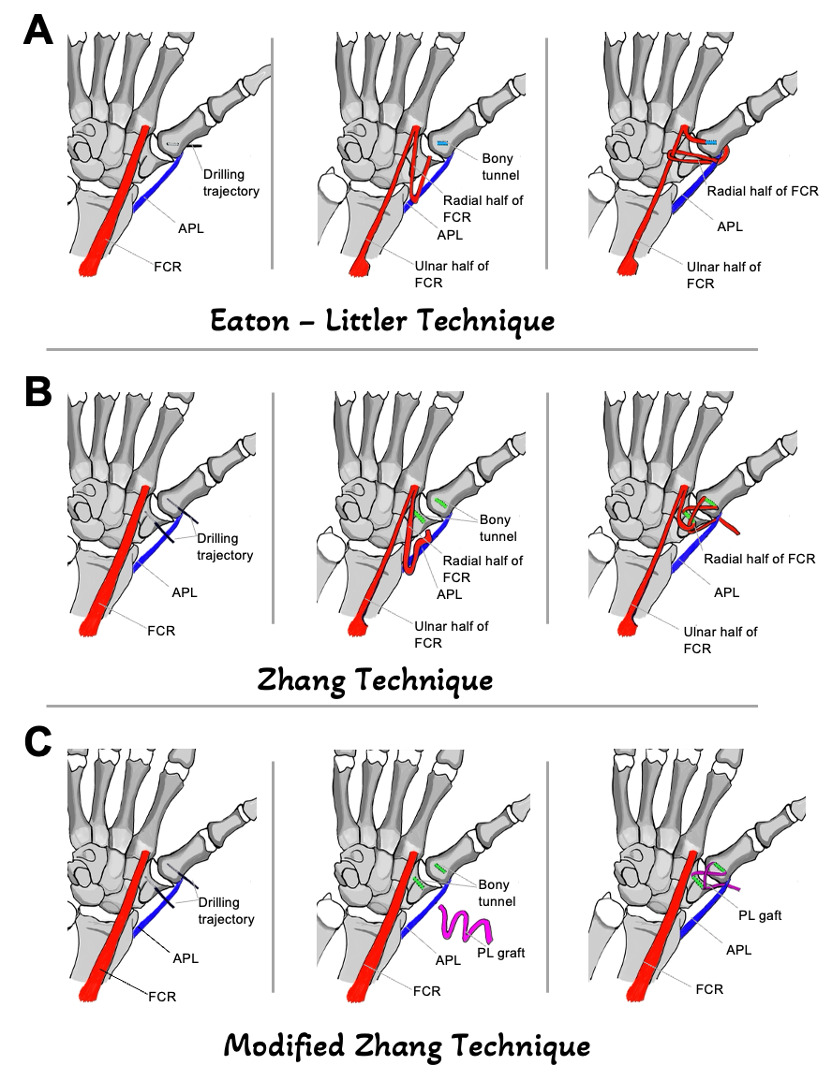

Historically, the anterior oblique ligament was considered the primary stabilizer, leading to the development of the Eaton-Littler procedure in 1973, which became the established gold standard for TMC reconstruction.10–12 However, recent anatomical and biomechanical studies have challenged this concept, suggesting that the dorsal ligament complex plays an equally important, if not more crucial, role in joint stability.3,9,13 These findings suggest that comprehensive reconstruction addressing both volar and dorsal structures may optimize stability restoration.8

In 2015, Zhang and colleagues introduced an alternative reconstruction technique addressing both ligament complexes, reporting favorable preliminary clinical outcomes.14 We modified the Zhang method by using the palmaris longus (PL) tendon as it provides a longer tendon graft and is easier to perform while preserving flexor carpi radialis (FCR) integrity. Despite these advances, comparative biomechanical data evaluating different reconstruction techniques remains limited, particularly in populations where traumatic mechanisms predominate.3

This study aimed to compare the biomechanical stability of the trapeziometacarpal joint following three ligament reconstruction techniques in a cadaveric model: the traditional Eaton-Littler method, the Zhang technique, and a modified Zhang technique utilizing a palmaris longus (PL) tendon graft .

Materials and Methods

Ethical Considerations

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (No. 426/HDDD-DHYD). All cadaveric specimens were obtained through the institutional body donation program with documented consent. The study adhered to established ethical guidelines for cadaveric research, with all specimen identities anonymized using coded identifiers.

Materials

We conducted a descriptive comparative biomechanical study utilizing 14 formalin-embalmed cadaveric hands (8 males, 6 females; mean age 78.5±10 years; range 52-91 years), yielding 21 total ligament reconstructions across the three techniques including Eaton–Littler, Zhang, and modified Zhang procedures.

Inclusion criteria included intact cadaveric hands preserved with standard formalin solution provided by the Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ho Chi Minh City. Exclusion criteria included: evidence of previous trauma or surgery to the TMC joint, inflammatory arthritis, congenital abnormalities, or anatomical variations affecting the TMC joint or surrounding structures.

Methods

Surgical Techniques

Each specimen underwent careful dissection exposing the TMC joint while preserving the FCR and PL tendons. The anterior oblique, dorsal radial, dorsal central, posterior oblique, and intermetacarpal ligaments were identified and subsequently sectioned to create complete TMC joint instability8,9 (Figure 1).

-

Eaton-Littler Technique (n=7): A radial half-slip of FCR tendon was harvested while maintaining its distal insertion. A 2.5mm bone tunnel was drilled through the first metacarpal base from dorsal-radial to volar-ulnar. The FCR slip was passed through the tunnel, tensioned with the thumb in neutral position, routed beneath the abductor pollicis longus tendon, and secured to itself using 3-0 nonabsorbable suture.

-

Zhang Technique (n=7): A radial half-slip of FCR was harvested proximally to the trapezial tubercle level. Two 2.5mm bone tunnels were created: one through the trapezium (dorsal to volar) and one through the first metacarpal base (radial to ulnar). The graft was passed through both tunnels in a figure-eight configuration, creating an “8” pattern on the volar aspect. The free end was secured to the abductor pollicis longus insertion and dorsal intercarpal ligament using 3-0 nonabsorbable suture.

-

Modified Zhang Technique (n=7): The specimens were reused from Zhang specimens after biomechanical measurement by completely removing the grafted tendon structure. The entire PL tendon was harvested. The reconstruction followed the Zhang technique protocol but utilized the PL tendon as the graft material. One free end of the graft was sutured and fixed at the figure-of-eight loop on the trapezium bone. The other free end was secured to the abductor pollicis longus insertion and the dorsal intercarpal ligament with 3-0 nonabsorbable sutures.

Graft dimensions were measured including length, width, thickness, and calculated cross-sectional diameter using precision calipers (accuracy ±0.01mm).

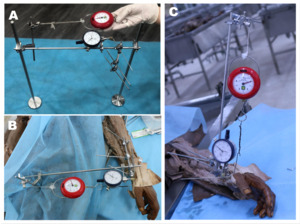

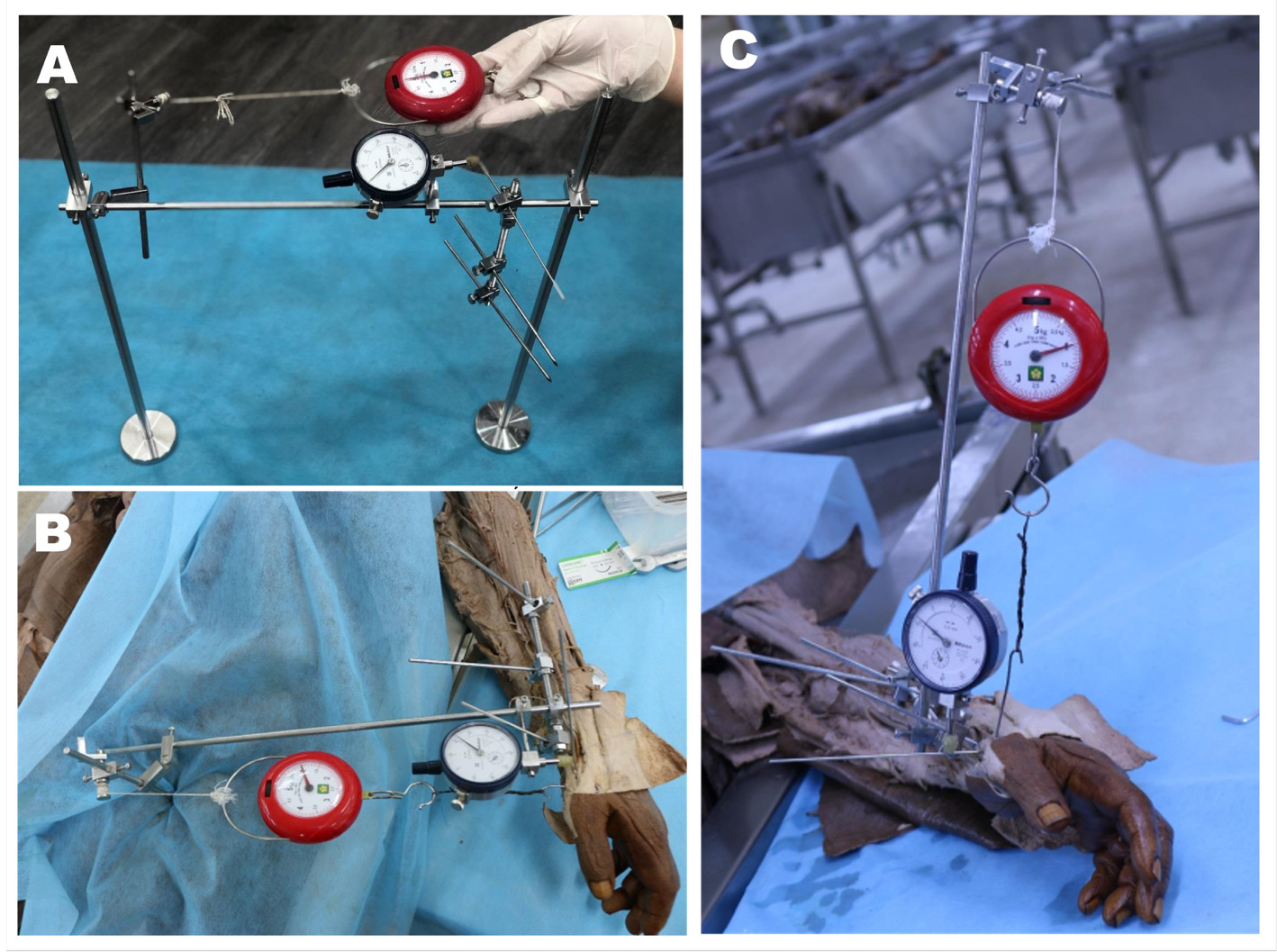

Biomechanical Testing

A custom external-fixation testing apparatus was constructed comprising a rigid frame with adjustable force application system and displacement measurement gauges (Mitutoyo, Japan; accuracy 0.01mm). To establish a stable testing platform, a 2.5-mm K-wire was first inserted through the trapezium. The measuring frame was then mounted onto this wire and rigidly secured to the radius with two 3.0-mm K-wires. Finally, a 1.4-mm K-wire was placed in the first metacarpal to measure displacement under applied loading. (Figure 2).

Testing was performed in four anatomical directions: dorsal (posterior), volar (anterior), radial (lateral), and ulnar (medial). Sequential loads of 10N, 20N, and 30N were applied in each direction using calibrated weights. The joint was returned to neutral position between measurements. Displacement was recorded as the change in position from the unloaded state.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis utilized Stata 14 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Given the small sample size and non-normal distribution verified by Shapiro-Wilk test, non-parametric testing was employed. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for pairwise comparisons between techniques. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data or median with interquartile range (IQR) for non-parametric data. Statistical significance was established at p<0.05.

Results

Specimen Characteristics

The study included 14 cadaveric hands with a mean donor age of 78.5±10 years (range 52-91 years). The gender distribution was relatively balanced with 57% male and 43% female specimens. All specimens demonstrated intact TMC joint anatomy without evidence of degenerative changes or previous injury upon initial dissection.

The biomechanical analysis reveals a clear distinction in the stability profiles offered by the three reconstruction techniques. The traditional Eaton-Littler method resulted in significantly greater joint displacement - indicating inferior stability - when compared to both the Zhang and modified Zhang techniques under dorsal, volar, and ulnar loading conditions. Notably, during radial displacement testing, no statistically significant difference in stability was detected among any of the three reconstructions. Furthermore, the standard Zhang and modified Zhang techniques demonstrated statistically equivalent biomechanical performance across all loading directions, with no significant differences observed between them. (Table 1, Figure 3)

Graft Characteristics

Comparative analysis revealed the PL tendon was significantly longer than the half-slip FCR (149.0±3.08mm vs 140.2mm [IQR 125-143], p=0.018). The PL demonstrated greater width (3.33mm vs 2.64±0.36mm, p=0.018) but reduced thickness (0.97±0.10mm vs 1.20mm, p=0.018). Crucially, these individual dimensional differences offset each other, as the calculated cross-sectional diameters of the two grafts were statistically equivalent (2.11±0.25mm for PL vs 2.08±0.30mm for half-slip FCR, p=0.499).

Discussion

This biomechanical study demonstrates that ligament reconstruction techniques addressing both volar and dorsal stabilizing structures provide superior multiplanar stability for the TMC joint compared to isolated volar reconstruction.8 Our findings show the Zhang and modified Zhang techniques are significantly more stable under dorsal, volar, and ulnar loading conditions than the traditional Eaton-Littler method. While all three techniques performed equivalently against radial forces, our modification using the palmaris longus (PL) tendon proved to be a viable alternative, offering biomechanical stability statistically indistinguishable from the standard Zhang technique, which uses a flexor carpi radialis (FCR) graft.

The management of TMC joint instability has undergone significant conceptual evolution over recent decades. Historically, the anterior oblique ligament was universally considered the primary stabilizer, establishing the theoretical foundation for the Eaton-Littler procedure.7,15 This technique, focusing exclusively on volar reconstruction, became the accepted gold standard and remains prominent in contemporary orthopedic literature.16 However, recent investigations have fundamentally challenged this paradigm. Current studies demonstrate that the dorsal ligament complex, particularly the dorsal radial ligament, is a primary stabilizing structure of the TMC joint.3,6,13,17 Given that dorsal ligaments are anatomically thicker and biomechanically stronger than their volar counterparts,17,18 recent research advocates for comprehensive, dual ligament reconstruction strategies that address both complexes to restore optimal stability.3,12

The Eaton-Littler Technique focuses exclusively on reconstructing the volar aspect to prevent dorsal subluxation.9–11 While this provides some resistance to dorsal forces, the technique lacks any dedicated dorsal reinforcement.12 When a volar force is applied, stability relies almost entirely on the passive tension of the native abductor pollicis longus (APL) tendon, leading to significantly greater displacement. The Zhang Techniques, in contrast, are designed to address both ligament complexes, aligning with the modern understanding of TMC anatomy.3,14 The volar figure-eight graft configuration provides robust resistance to dorsal displacement. Crucially, the technique also reinforces the dorsal side by anchoring the graft to the dorsal intercarpal ligament (Figure 4). This added dorsal buttress directly counteracts volar forces, explaining its superior stability in both directions when compared to the isolated volar repair of the Eaton-Littler method.3,12

Interestingly, our analysis revealed no statistically significant differences emerged between techniques when resisting radial displacement. This equivalence can be attributed to the specific technical elements of the Eaton-Littler reconstruction, which incorporates a tendon loop configuration anchored to the abductor pollicis longus insertion (Figure 4). This construct provides robust lateral support that effectively compensates for the absence of dorsal reinforcement in this specific loading direction. The Zhang method achieves similar lateral stability through comprehensive four-directional stabilization, resulting in comparable biomechanical performance.

These experimental findings support fundamental reconsideration of TMC reconstruction principles. The comprehensive approach embodied by the Zhang technique, addressing both volar and dorsal structures, provides superior multiplanar stability compared to isolated volar reconstruction.14 This enhanced stability may prove particularly important in younger, active patients and those with high-energy injury mechanisms disrupting multiple stabilizing structures.

In this study, we introduced a modified Zhang technique, which substitutes the half-slip flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendon with a full-thickness palmaris longus (PL) tendon graft. Biomechanically, this modification demonstrated a stability profile that was statistically equivalent to the standard Zhang technique under all multi-directional loading conditions (p>0.05). This comparable performance can be attributed to the nearly identical cross-sectional diameters of the two grafts (p=0.499). From a clinical perspective, the PL tendon presents several practical advantages. Its use preserves the integrity of the FCR tendon, an important consideration for maintaining full wrist function, especially in younger, active patients. The PL tendon is also technically less demanding to harvest and provides greater graft length (149 mm vs 140 mm, p=0.018), which can facilitate easier surgical manipulation and more secure fixation.

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the use of a formalin-preserved cadaveric model cannot fully replicate the in vivo environment. These specimens lack the dynamic muscular stabilization and proprioceptive feedback mechanisms present in living tissue, which play a significant role in joint stability. Second, the elderly specimen population (mean age 78.5 years) may not accurately represent the tissue characteristics of the younger patients who often sustain traumatic TMC injuries. Third, our biomechanical testing protocol involved static, sequential loading and did not account for the effects of cyclic loading or fatigue failure, which are highly relevant to long-term clinical outcomes.19 Fourth, this study evaluated only the immediate, time-zero stability of the reconstructions and could not consider the biological processes of tendon graft healing and remodeling that occur in vivo. Finally, while the sample size was sufficient to detect the observed differences, it was relatively small and may have been inadequate for identifying more subtle, clinically relevant variations between the techniques. The custom-made testing apparatus, while calibrated, was also a limitation, and more advanced equipment could provide even more precise measurements .

Conclusion

This biomechanical study demonstrates that ligament reconstruction techniques addressing both volar and dorsal stabilizing structures of the TMC joint provide superior multiplanar stability compared to isolated volar reconstruction. The Zhang and modified Zhang techniques showed significantly less displacement under multiplanar loading conditions compared to the traditional Eaton-Littler method. The PL tendon represents a viable alternative graft source with equivalent biomechanical properties to the FCR tendon. These findings provide evidence-based guidance for surgical decision-making in TMC joint reconstruction, particularly in younger patients requiring robust, long-lasting stability restoration.

Author Contribution

Quyen Le Ngoc: Conceptualization; Methodology; Project administration; Data curation; Writing original draft; Review and editing.

Hieu Nguyen Chi: Writing; Review and editing; Responsible for correspondence and article submission.

Tan Khuong Anh: Conceptualization; Investigation (performing cadaveric procedures); Data curation; Formal analysis; Visualization (creating descriptive illustrations)

Conflict of interests

We declare that we have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper

__volar_displacement_(.png)

__volar_displacement_(.png)