1. Introduction

Femoral fractures are divided based on the location of the fracture site, their morphology and the mechanism of injury. The major categories include proximal femur fractures, which encompass femoral neck and intertrochanteric fractures; subtrochanteric fractures, occurring just below the lesser trochanter; and femoral shaft fractures, involving the diaphyseal region. The fractures of each type have different biomechanical and clinical aspects. The proximal femur fractures are usually related to osteoporosis in older patients, and for this reason, the fixation methods applied to restore hip stability need to be very well thought out. The subtrochanteric fractures are influenced by high compressive and tensile forces so it is very important to carry out anatomical reduction and rigid fixation if early mobilization can be achieved. The femoral shaft fractures are generally the result of high-energy trauma, and the treatment is usually the application of intramedullary devices that not only provide stability of the fracture but also allow the preservation of the surrounding soft tissues.1

Femoral shaft and subtrochanteric fractures represent some of the most severe injuries seen in orthopedic traumas. It is often due to vehicle collisions or falls from height or even in older patients with fragile bones due to osteoporosis. These fractures are associated with substantial morbidity due to expensive soft tissues disruption, high blood loss and prolonged functional impairment. Subtrochanteric fractures pose unique biomechanical challenges due to high compressive and tensile forces across the proximal femur, making anatomical reduction and stable fixation essential for optimum recovery.

Unstable femoral shaft and subtrochanteric fractures are most commonly treated by open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). The modern fixation generally involves intramedullary nailing thus achieving biological fixation, early mobilization, and less soft tissue stripping as compared to the historical plate constructs.1 Postoperative wound complications are, however, the main cause of patient discomfort despite the progress in implant design and surgical technique. Wound dehiscence, deep incisional surgical site infection (SSI), and organ/space SSI not only prolong the patient’s stay in hospital and delay rehabilitation but are also, in clinical and economic terms, associated with increased reoperation, long-term disability, and, in extreme cases, loss of limb or life.2

The incidence of SSI after femoral fracture fixation reported in the literature varies a lot but the infection rates are consistently higher than those in elective orthopedic procedures thereby indicating the severity of the trauma cases and the physiological state of the patients, who are more vulnerable. Finding both modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors is a decisive step on the way to the perioperative strategies that stratify risk and thus prevent complications.3 In the past, researchers across the orthopedic subspecialties, have pointed to obesity, malnutrition, anemia, diabetes, and prolonged operative duration as the factors that contribute to infection and wound breakdown.4 However, a thorough investigation into these risk factors in femoral ORIF and across various clinically distinct wound outcomes such as dehiscence, deep SSI, and organ/space SSI remains limited.

The significant morbidity led by the postoperative wound complications in this patient cohort calls for the understanding of the causes of these conditions urgently. The current study leverages data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP), a reliable and diverse clinical registry, to analyze patient, operative, and physiologic factors associated with wound dehiscence, deep incisional SSI, and organ/space SSI within 30 days after femoral ORIF.5

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study utilizing data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database.6 ACS-NSQIP prospectively collects clinical data from participating hospitals, including preoperative comorbidities, intraoperative variables, and 30-day postoperative outcomes. Data abstraction follows strict clinical definitions and is performed by trained surgical clinical reviewers, ensuring high validity and reliability.sza

2.2. Study Population

Patients who underwent open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the femur between 2016 and 2022 were identified using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 27245. This code includes open surgical treatment of a femoral shaft or subtrochanteric femoral fracture using an intramedullary implant, with or without interlocking screws and/or cerclage. Inclusion criteria comprised adult patients aged ≥18 years undergoing femoral open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). Patients were excluded if they had incomplete demographic or outcome data, missing key covariates, or underwent concurrent major procedures that could confound postoperative outcomes.

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest were the occurrence of wound dehiscence, deep incisional infection, and organ space infection. Wound dehiscence (WD) was defined as the separation of a surgical incision, which can be partial or complete and may or may not have signs of infection. A deep incisional surgical site infection (DISSI) is an infection of the deep soft tissues, such as the fascial and muscle layers beneath the skin. Criteria for DISSI include purulent drainage from the deep incision, or if the deep incision is deliberately opened by the surgeon due to suspicion of infection, and the patient has at least one sign of infection such as fever, localized pain, or tenderness. An organ space infection (OSI) involves infection of any part of the body, other than the incision, which was opened or manipulated during the primary procedure. OSI can be diagnosed by purulent drainage from a drain placed into the organ or space, or from evidence of an abscess or infection in these deep tissues on a CT scan.

2.4. Independent variables

Patient-level variables included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, diabetes mellitus, steroid use, bleeding disorders, functional status, preoperative anemia, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status class. Operative factors included operative duration, wound classification, emergent vs elective status, and need for perioperative blood transfusion. Hospital length of stay and discharge disposition were also recorded.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the cohort. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as means ± standard deviation or medians with interquartile range, as appropriate. Bivariate analyses were performed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables.

Univariates tested for significance included age, sex, BMI, ASA classification, total operating time, anesthesia type, diabetes, preoperative steroid use, functional status, dialysis, cancer, hypertension requiring medication, preoperative albumin, preoperative platelets, and preoperative WBC. Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to identify independent predictors of each infection outcome, adjusting for clinically relevant variables and those with p < 0.05 in univariate analyses.7 Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.8 The models’ variances are reported using the R2 statistic.9 Multicollinearity was evaluated via variance inflation factor thresholds. Goodness-of-fit was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. All hypothesis testing was two-tailed, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 19.0 (JMP Statistical Discovery LLC. Cary, NC).

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study analyzed publicly available, de-identified data and was therefore deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board review and did not require informed consent. Our institution (Brown University) issued a non-human subject determination for this study.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort demographics

The cohort consisted of 63727 cases, of which 69% were female. The median age was 82 years, with an interquartile range of 72-89 years, and a range from 18->90 years (NSQIP does not report specific ages greater than 90 years of age to preserve patient privacy). The median body mass index (BMI) was 24.6, with an interquartile range from 21.3-28.4. The American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) classification distribution was Class 1- 1%, Class 2- 17%, Class 3- 63%, Class 4- 20%, and Class 5- 0%. Table 1 summarizes the comorbidities in the cohort.

3.2. Wound dehiscence

Among patients undergoing femoral ORIF, the 30-day odds of wound dehiscence were significantly associated with higher BMI and chronic steroid use. In multivariable nominal logistic regression, BMI remained an independent predictor (adjusted OR per kg/m² 1.06; 95% CI, 1.03–1.10; p=0.004). Chronic steroid use conferred more than a threefold increase in risk (adjusted OR 3.54; 95% CI, 1.35–9.34; p=0.0105). Operative time demonstrated a nonsignificant trend toward higher risk (adjusted OR per minute 1.003; 95% CI, 0.998–1.007; p=0.21), and perioperative platelet transfusion was not associated with dehiscence (adjusted OR 1.002; 95% CI, 0.997–1.006; p=0.47). The overall model fit was statistically significant (χ²=14.84, df=4, p=0.0051) with modest explanatory power (R²=0.031) and moderate discrimination (AUC=0.698). These findings indicate that obesity and steroid exposure are the principal, clinically meaningful determinants of wound disruption after femoral fixation, whereas procedure duration and platelet transfusion have lesser or no independent effects after adjustment.

3.3. Deep incisional surgical site infection

A nominal logistic regression model was run to evaluate predictors of 30-day deep incisional SSI following femoral fracture fixation. The overall model was statistically significant (χ² = 48.54, df = 6, p < 0.0001) with modest explanatory capability (R² = 0.059) and fair discrimination (AUC = 0.728), indicating meaningful but incomplete capture of factors contributing to infection risk.

Significant predictors included operative time, low preoperative albumin, high body mass index, general vs. local anesthesia, and preexisting renal dysfunction

Each additional minute of operative time increased the odds of deep infection by ~0.7%. Over the full operative range, this translated to a large cumulative risk effect, emphasizing the importance of procedural efficiency and complexity as contributors to postoperative infection.

Lower albumin levels were associated with significantly higher infection risk. Hypoalbuminemia reflects impaired nutritional and inflammatory status, reinforcing the importance of physiologic reserve and perioperative nutritional optimization.

Higher BMI independently increased deep SSI risk. Each 5-unit BMI increase yielded approximately a 28% increase in infection odds. This aligns with known associations between obesity, wound tension, and impaired tissue oxygenation.

General anesthesia was associated with a significantly increased risk of deep SSI compared with neuraxial techniques or monitored anesthesia care (MAC). This may reflect physiologic advantages of neuraxial anesthesia (reduced blood loss, enhanced perfusion, improved immune response), or patient-selection factors favoring sicker or more complex cases receiving general anesthesia.

Preexisting renal dysfunction significantly increased infection risk, likely related to impaired immunity, inflammation, and wound healing.

3.4. Organ Space infections

A nominal logistic regression model was run to evaluate predictors of 30-day organ/space SSI following femoral ORIF. The model was statistically significant (χ² = 23.98, p = 0.0002) with modest explanatory capacity (R² = 0.037) and good discrimination (AUC = 0.7006), indicating meaningful but multifactorial drivers of deep postoperative infection risk. Significant Predictors included longer operative time and lower preoperative albumin.

Each additional minute of operative duration increased organ/space SSI risk by ~0.55%. Across the full operative time range in the cohort, this effect accumulated substantially, suggesting operative complexity, prolonged exposure, and tissue handling as contributors to deep infection.

Hypoalbuminemia was independently associated with higher organ/space SSI risk, underscoring the importance of nutritional and inflammatory status in deep postoperative infectious complications. This finding aligns with established literature on malnutrition and impaired immune defense.

Although obesity showed a trend toward increased risk, it did not reach statistical significance in this model, in contrast to its strong role in superficial and deep incisional SSI.

Age also did not significantly influence organ/space SSI risk after adjustment, suggesting biologic age alone is not a primary driver. Smoking approached significance and nearly doubled odds of organ/space infection, though confidence intervals crossed unity. This trend is clinically meaningful and consistent with known vascular and immune impairment in smokers.

The contribution of each of these clinical variables to the outcomes of wound dehiscence, deep SSI and organ space SSI are summarized in table 2 and figure 2.

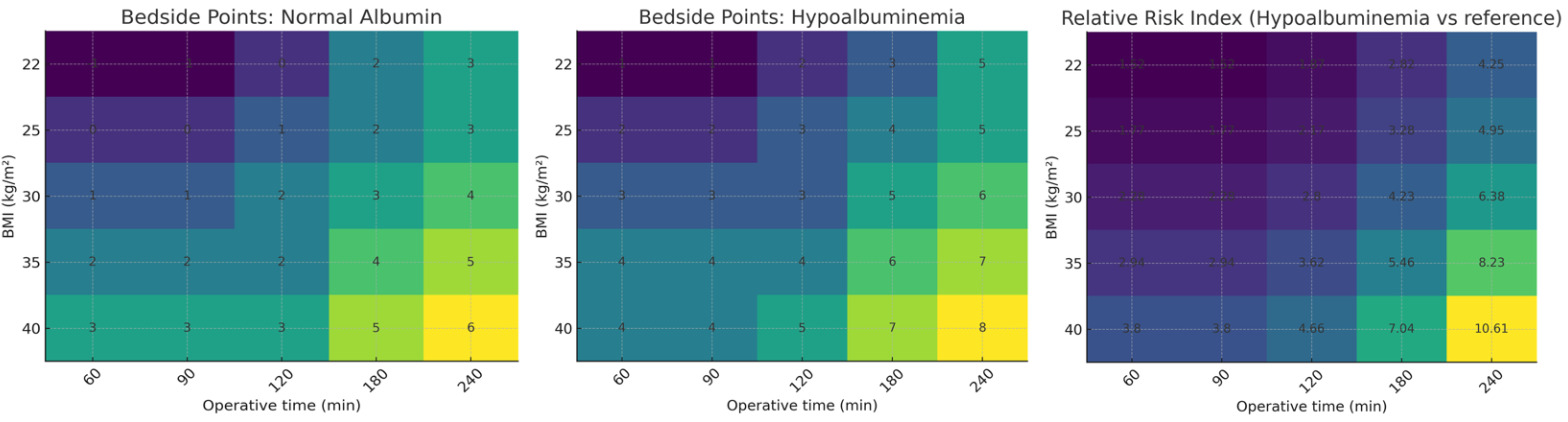

Across the 3 outcomes, operative time, BMI and low albumin were the most common crosscutting risk factors. A simplified bedside risk-scoring system was constructed to translate multivariable model coefficients into an intuitive clinical tool for estimating postoperative infection risk following femoral ORIF Figure 3. Variables selected for scoring—body mass index (BMI), operative duration, and preoperative albumin—were chosen based on their consistent and biologically plausible associations across the dehiscence, deep incisional SSI, and organ/space SSI models. Logistic regression β-coefficients were converted into points using a standardized approach in which approximately 0.30 units of log-odds (corresponding to an odds ratio of ~1.35) equated to one point, allowing clinically meaningful gradations in risk. For BMI and operative time, points were calculated relative to clinically relevant reference thresholds (BMI 25 kg/m² and operative duration 90 minutes), with increments assigned proportionally to the magnitude of the β-coefficient per unit increase. Because hypoalbuminemia (albumin <3.5 g/dL) conferred increased risk in both deep and organ/space SSI models, its effect was estimated by averaging the inverse of the protective odds ratios from each model and converting the resulting value into points. The cumulative score thus approximates the additive effect of these predictors on log-odds of infection, and corresponding heatmaps were generated to illustrate bedside point totals and relative-risk indices across combinations of BMI, albumin status, and operative time. This method provides a transparent, physiology-based risk stratification tool suitable for perioperative planning and patient counseling.

4. Discussion

In this nationwide cohort of femoral shaft and subtrochanteric fracture patients undergoing open reduction with internal fixation, numerous independent predictors associated with 30-days postoperative wound dehiscence, deep incisional SSI, and organ/space SSI were recognized. Higher body mass index (BMI), extended operative time and low preoperative albumin were significant predictors of worse wound outcomes. Furthermore, corticosteroid use was also associated with significantly higher odds of dehiscence, and both renal insufficiency and general anesthesia were independent predictors of deep incisional infection. Smoking was also a significant factor in predicting results.

Multiple studies have shown that obesity is a strong predictor of wound complications, including SSI and dehiscence after orthopedic surgery. Obesity contributes to impaired tissue oxygenation, increased wound tension, greater soft-tissue dissection requirements, and a pro-inflammatory metabolic state, all of which predispose to infection and mechanical wound breakdown (10–12). Orthopaedic trauma literature has reported higher rates of infection and reoperation among obese patients undergoing lower-extremity fracture fixation.10,11 Our findings confirm this association, as higher BMI increased both dehiscence and deep SSI risk. Given that BMI is largely non-modifiable in the acute trauma setting, mitigation strategies should focus on enhanced soft-tissue protection, layered closure techniques, and intensified postoperative wound surveillance in obese patients.

Prolonged operation time was strongly linked to increased odds of both deep and organ/space SSI. Longer operations tend to increase bacterial exposure, tissue desiccation, and thermal injury. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that procedures exceeding standard operative times increased SSI risk by 30–50%,12 and orthopaedic trauma reports show similar associations in lower-extremity fracture fixation.13,14 Clinically, strategies to reduce modifiable delays—such as improved operating room efficiency, early fracture stabilization, utilization of experienced surgical teams, and staged approaches for highly complex injuries—may reduce infection burden.

Preoperative hypoalbuminemia was a significant predictor of deep and organ/space SSI. Serum albumin reflects nutritional status and physiologic reserve, and levels <3.5 g/dL have been associated with impaired immune response, decreased collagen synthesis, and poor wound healing.15 Several studies in orthopaedic and general surgery populations have demonstrated that low albumin significantly increases postoperative infectious complications.16–18 Our results reiterate the importance of nutrition, particularly in vulnerable populations such as elderly or chronically ill patients. Preoperative identification of malnutrition and targeted nutritional intervention may improve outcomes.

Renal insufficiency has been shown to increase the likelihood of deep SSI by itself. The patients who are suffering from chronic kidney disease (CKD) frequently show dysfunctional immune system, anemia, microvascular dysfunction, and the changes in the body’s metabolism caused by the lack of filtering that altogether contribute to the impairment of healing and the defense against the infection. CKD is linked with the increased risk of infection, reoperation, and death after fracture surgery.13,19

Long-term systemic corticosteroid therapy was associated with a risk of dehiscence 3.2 times that of those not receiving long-term therapy. Steroids inhibit the mobilization of inflammatory cells, proliferation of fibroblasts, and collagen deposition all necessary components of healing. Steroids in the long term raise the odds of wound complications such as dehiscence and infection.20,21 Our data confirm the biological plausibility of this association in femoral ORIF patients. Although abrupt cessation of steroids is generally not advised, plans for perioperative reduction, stress-dose steroid protocols, and better wound monitoring may be beneficial in this high-risk group.

Our study also found that general anesthesia increased the risk of deep surgical site infection compared to neuraxial anesthesia. Previous studies suggest that reduced perioperative immunosuppression, decreased blood loss, and increased tissue perfusion resulting from neuraxial anesthesia can combine to reduce risk of infection.20,21 While patient selection is certainly a factor in this relationship, anesthesia type may be a modifiable component of an overall strategy to reduce SSIs.

Smoking almost doubled the risk of organ/space infection, although this result was not statistically significant. Smoking deranges microcirculation, immune cell function, mucus clearance, and bone and wound healing, and has been consistently associated with infection and nonunion after fracture fixation.22,23 This trend is clinically accurate and reinforces existing institutional practices which recommend perioperative smoking cessation where feasible.

The results focus one the need for thorough preoperative assessment, risk classification, and implementation of specific measures aimed at patient improvement before surgery to lower the rates of postoperative complications and improve procedure outcomes. A timely nutritional status assessment, offering support for quitting smoking, close monitoring of patients with kidney problems or those on corticosteroid, and measures to facilitate surgical efficiency may all act as factors leading to better postoperative results. There is a need for further prospective studies to determine the impact of preoperative optimization protocols and enhanced recovery pathways on the incidence of complications in high-risk orthopedic trauma patients.

5. Conclusion

Wound dehiscence, deep SSI and organ/space SSI after femoral fracture ORIF are independently predicted by several risk factors which highlight modifiable perioperative targets—particularly nutrition and anesthesia strategy—to reduce infection burden in this high-risk surgical population.

FUNDING

No funding was received for this work

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Not applicable

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

None