Introduction

Ewing Sarcoma is an uncommon and aggressive malignancy that primarily affects adolescents, often exhibiting itself with subtle symptoms that delay diagnosis.1 Ewing sarcoma can be interpreted as an umbrella term, given that it encompasses Ewing Sarcoma of bone, Extraskeletal Ewing Sarcoma, and Malignant small cell tumor of the chest wall; otherwise referred to as the Askin tumor.1 The following cohort of diseases are characterized by their similar histological and immunohistochemical reports. The entities belong to the same family of small round blue cell tumors with analogous biological properties. Ewing Sarcoma is driven by non-random chromosomal translocation, with the two most prevalent genes involved being EWS and FLI1.2 The cancer has the potential to occur in nearly all bone or soft tissue, with the most seen anatomical locations being the pelvis, axial skeleton, and femur. Clinically, patients usually observe localized pain and or edema at the targeted anatomical region.3

Epidemiological data suggest that people of Caucasian ancestry have been generally proved to be significantly more susceptible to Ewing’s Sarcoma. Non-Caucasian populations had drastically less incident ratios like 0.54 in Asian/Natives and 0.12 in African Americans.4

The authors present the case of a 46-year-old man with complaints of left posterior flank pain. The patient is of South Asian ancestry, additionally has a history of Nephrolithiasis (kidney stones) and a negative family history of cancer. Then admitted to an outpatient clinic, the patient underwent a pelvic and abdomen CT scan revealing an unidentified mass in the left retroperitoneum. Further pathological sampling led to the identification of the malignancy as Ewing’s Sarcoma, and the precise location to be in close proximity to the aorta, partially encasing it and developing under the sub aorta. This case is therefore novel in its demographics, location, and diagnostic intricacy. Moreover contributing to the void of knowledge in medical literature and history that has still yet to flourish, urging the need for a more inclusive documentation for unusual presentations of malignancies.

Case Presentation

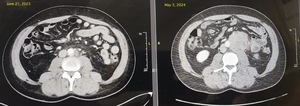

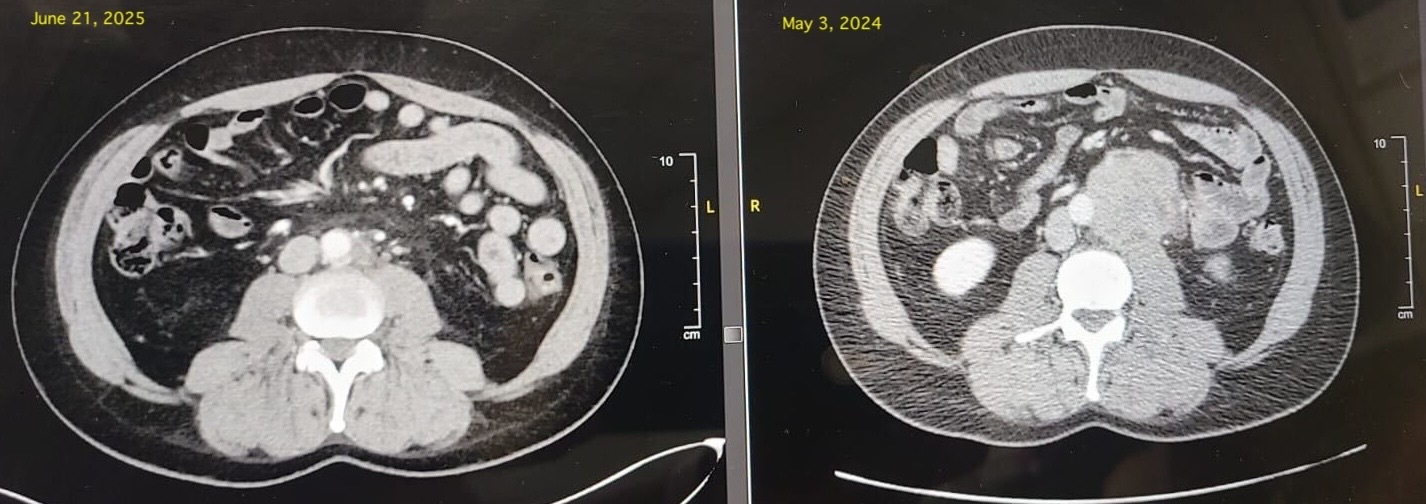

A 46-year old male with a history of kidney stones presented with discomfort and pain in the left posterior flank, progressively worsening over the past few weeks. Initially, the patient assumed the pain was related to a new occurrence of kidney stones. After going on vacation where the patient engaged in physical activity, the patient sought medical attention due to worsening pain. After visiting an outpatient clinic, the patient was recommended to get a CT abdomen and pelvic scan to check for the kidney stone. The scan revealed no stones or hydronephrosis in the right kidney, but 1mm stones of the lower pole in the left kidney. The scan also revealed a solid irregular mass within the left retroperitoneum at the level of the L3-4 disc measuring 5.8 x 5.2 x 6.0 cm that partially encases the aorta and appears to grow underneath the aortic contour. The ureter was identified and appeared to be deviated laterally by the mass. Given the positive findings, the patient was suggested to undergo percutaneous sampling to confirm tissue diagnosis.

The pathology reports revealed that sections of the retroperitoneal mass demonstrated a proliferation of relatively monotonous small round blue cells. Although necrosis was identified, the tumor did not show any obvious mitotic activity. The overall histologic and immunohistochemical findings were highly suspicious for Ewing sarcoma.

Due to the complicated nature of the mass, the patient was advised to receive chemo through the right dual lumen power injectable chest port via the right IJV. After revaluation, no additional pathologically enlarged or hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy was identified within the retroperitoneal, pelvic sidewall, or inguinal nodal groups. After a reevaluation a year later, there were small additional masses recorded, but could not be identified through the CT scan. They were sent for additional MRI testing and identification.

Discussion

This case presents a rare and atypical manifestation of Extraskeletal Ewing’s Sarcoma (EES), identified in the left retroperitoneum of a middle-aged South Asian male. The patient initially presented with lower left flank pain, and had a past known history of nephrolithiasis, which led clinicians to presume a recurrent kidney stone episode. However, subsequent imaging revealed a 7 cm soft tissue mass, encasing the aorta at the L3–L4 disc level. This case highlights key limitations in early detection, including reliance on less sensitive imaging modalities such as ultrasound, which may delay diagnosis and prognosis. The rarity of retroperitoneal EES shows the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis when clinical symptoms persist, especially in patients with predisposing histories.5

While classic Ewing’s sarcoma typically arises in long bones and predominantly affects individuals under the age of 30, this case diverges from that normal scenario.6 The tumor originated from soft tissue in the retroperitoneum which is an uncommon site for EES and was observed growing along the aortic contour, partially encasing the vessel without complete obstruction. Such extraskeletal locations have been reported in the literature but remain infrequent, particularly when involving structures as critical as the abdominal aorta.6 Compounding its rarity is the patient’s age and ethnicity; EES has a significantly lower incidence in non-Caucasian populations, especially among South Asians.4

Although Ewing Sarcoma is a rare malignancy, a considerable volume of research has been published. Upon conducting a comprehensive literature review, the entity seems to be well-studied. A significant proportion of cases published being of skeletal origin, in light of the fact that the cancer is predominantly targeting the long bones.7 Ewing sarcoma is one of the few malignancies accounting for less than 1% of diagnosed cancers each year and can be attributed to a significant amount of fatalities yearly.8 Risk factors for Ewing’s include age, tumor extent,anatomical sites in the cranial and or axial bones, tumor size, or numerous sites of metastasis.9 The development of advanced molecular techniques, notably cytotoxic chemotherapy, has rapidly improved therapeutic outcomes in not only Ewing’s Sarcoma, but many other variants.10 Additionally, the chemotherapy can be strongly assisted by stem-cell rescue. Tyrosine kinases (TKs), which is an overexpressed sarcoma tumor, contains cell lines that could hypothetically be pathways for new therapies.11 In contrast, when integrating demographics and key words to the literature review like South Asian, retroperitoneal, extraskeletal, aortic encasement, and nephrolithiasis, the number of case reports sharply diminishes.

A review of published cases reveals very few reports that match the constellation of findings observed in this patient: a large-volume (7 cm), extraskeletal tumor with partial aortic encasement, occurring in a demographic and anatomical location rarely documented. Its anatomical proximity to vital vascular structures not only complicates surgical and medical management but also demands greater pharmacological precision. Literature suggests that EES in such locations presents higher therapeutic challenges due to increased risk of local invasion and limited surgical accessibility.12 Furthermore, the scarcity of similar cases in South Asian individuals raises epidemiologic and genetic questions about tumor susceptibility. The reduced incidence of Ewing’s sarcoma in non-Caucasian populations may stem from genetic protective factors or underreporting of cases.13

In conclusion, this case underscores the need for increased clinical awareness when evaluating persistent flank pain, particularly in patients with a history that may bias initial diagnosis. It reinforces the importance of comprehensive imaging and broad differential diagnoses in unusual clinical presentations, while also prompting further exploration of EES pathology and incidence in ethnically diverse populations.14 This case highlights an unique presentation of Extraskeletal Ewing’s Sarcoma, both in anatomical location and patient demographic.

Patient Perspective

The patient, a middle-aged father of young children, experienced overwhelming emotional and psychological distress when learning of his diagnosis. He expressed a deep sense of uncertainty when informed that Ewing Sarcoma lacks a standardized treatment protocol for adults, which heightened his anxiety about achieving long-term recovery. The initial shock of diagnosis, combined with fears about the future, led to a pessimistic outlook and emotional withdrawal.

Chemotherapy proved to be physically and mentally grueling. The patient described each session as feeling as though he was “on the verge of death.” Over time, he became increasingly concerned about cumulative side effects, particularly the progressive decline in his platelet and white blood cell counts, which posed additional risks. The radiation therapy plan also raised early fears about potential collateral damage to surrounding organs.

Witnessing his own physical deterioration, especially noticeable weight loss and hair loss, was psychologically torturous. These visible reminders of illness compounded the emotional toll. However, as acute side effects have subsided and hair has begun to regrow, the patient reports a renewed sense of optimism and hope. He now looks ahead to his next quarterly scan with cautious anticipation and a more positive mindset.