Introduction

Craniofacial hypoplasia may be congenital or secondary to therapeutic interventions, such as radiotherapy in pediatric patients with head and neck cancer that leads to tissue and bone growth abnormalities over time.1 These structural anomalies can obstruct the airway in 31% of cases and make bag-valve-mask ventilation challenging.2 As a result, difficult airways pose a high risk of adverse perioperative events and remain a complex aspect of anesthetic care. In practice, general anesthesia (GA) is often favored due to its perceived advantage of securing the airway.3 Regional anesthesia (RA) is an alternative to GA and helps avoid airway manipulation.4 However, there is inconclusive evidence in literature to confirm the superiority of RA over GA in patients with anticipated difficult airways.4 While the choice of technique may depend on the provider’s preference, multiple factors should be considered. Here, we present a case of a 54-year-old male with craniofacial hypoplasia and several comorbidities undergoing elective surgery to discuss elements involved in anesthetic planning and airway management.

Case Presentation

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

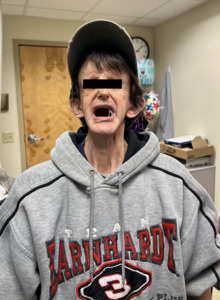

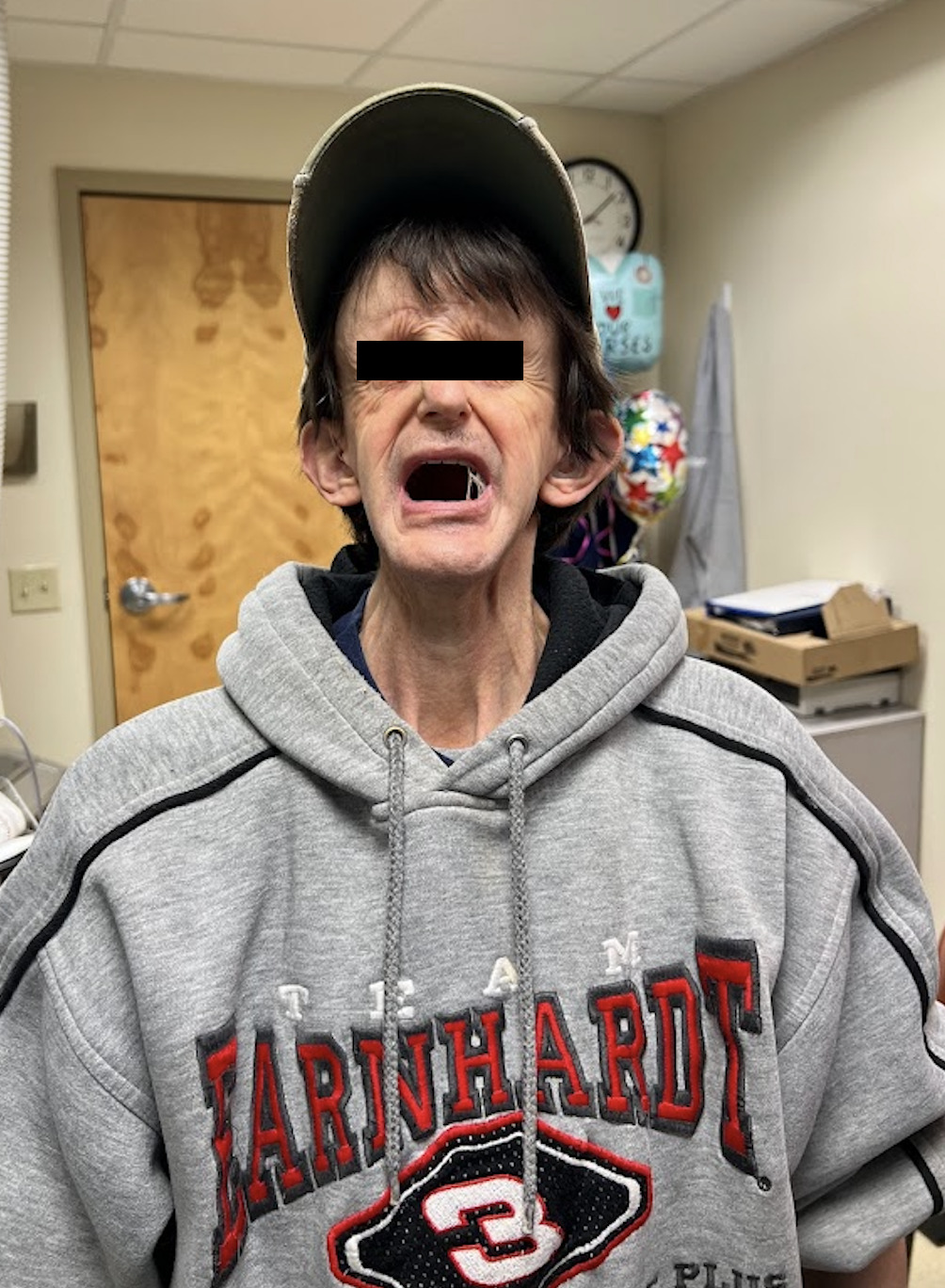

A 54-year-old male (45 kg, 172.7 cm) presented for a penile implant insertion for severe erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy. He was classified as ASA physical status class III. Pertinent medical history included craniofacial hypoplasia from childhood surgical interventions and radiation for sinus cancer (rhabdomyosarcoma), moderate mitral regurgitation, mild tricuspid regurgitation, pulmonary hypertension, recurrent esophageal strictures requiring multiple dilations, and anemia. Physical examination revealed a small head and airway with a Mallampati score of III (Figure 1). There was full neck range of motion; however, both thyromental distance and mouth opening were restricted to less than three fingerbreadths. His previous surgery required successful awake fiberoptic intubation with a pediatric-size 6.0 endotracheal tube. Given these findings, spinal anesthesia was planned with awake fiberoptic intubation on standby, with this treatment plan expected to result in adequate analgesia without airway or other hemodynamic compromise.

The patient was premedicated with midazolam 2 mg IV and dexmedetomidine 8 mcg IV for anxiolysis. Spinal anesthesia, consisting of 2.5 mL 0.5% bupivacaine and 10 mcg of fentanyl, was administered in the sitting position at the L3-L4 interspace using a Whitacre 25-G needle via the midline approach. He was then positioned supine and achieved sensory blockade up to the T8 level. Ketamine 10 mg IV was added for additional pain control, and glycopyrrolate 0.1 mg IV was given prophylactically to reduce secretions. During the procedure, there was a slight decrease in blood pressure, which was effectively treated with ephedrine 10 mg IV. The remainder of the case was completed with stable vital signs and no anesthetic complications. Acetaminophen 650 mg IV was given at the end for postoperative analgesia. In the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), the patient remained pain free and was spontaneously breathing with a patent airway. He was safely discharged the following day.

Management and Outcomes

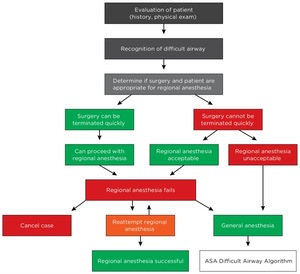

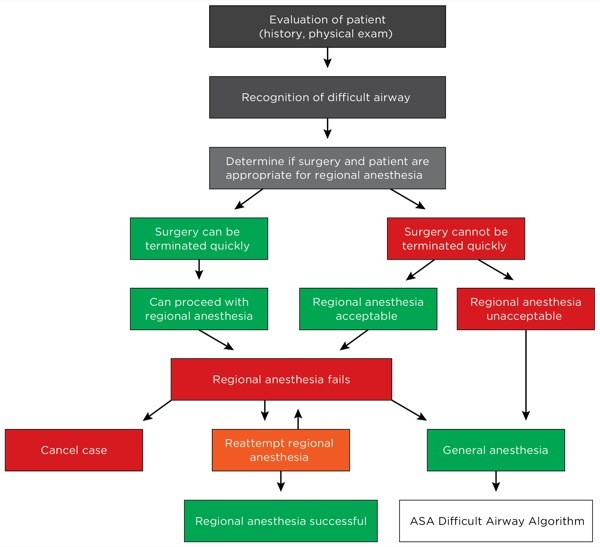

The patient exhibited many features consistent with the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) predictors of a difficult airway, including thyromental distance and mouth opening of less than three finger breadths, along with Mallampati class >2.4 These findings likely stem from his craniofacial hypoplasia following childhood treatment for sinus cancer, with radiation-induced fibrosis contributing to trismus and other possible anatomical variations affecting airway management.5 As a result, using conventional modalities such as direct laryngoscopy was not feasible.6 Craniofacial abnormalities are also associated with a 31% incidence of upper airway obstruction at induction and a 25% rate of difficult bag-valve-mask (BVM) ventilation.2 Additionally, anatomically difficult airways are less likely to have first-attempt intubation, with each subsequent attempt increasing the risk of airway trauma, severe hypoxia, and cardiac arrest.7,8 When difficult BVM ventilation is combined with failed intubation, patients are faced with a 67% chance of multiple attempts.3 Moreover, patients who receive radiation for head and neck cancer may develop radiation-induced cranial nerve injury years later, predisposing them to airway obstruction following extubation.9 By opting for spinal anesthesia, we minimized the risks encountered during airway manipulation. Patients who are high-risk for difficult mask ventilation or intubation should be considered for RA10 (Figure 2).

While anatomical characteristics are commonly recognized when evaluating for a difficult airway, physiological factors should also be considered. A physiologic difficult airway refers to underlying conditions such as impaired oxygenation, hypotension, metabolic acidosis, or right ventricular failure, all of which can precipitate cardiovascular collapse during airway management.11 Patients with pulmonary hypertension, like our patient who had underlying valvular pathology, are vulnerable during induction and intubation. They may experience impaired cardiac filling from shifts in intrathoracic pressure, hypoxemia, and hypercarbia that increase pulmonary artery resistance.12,13 As pulmonary hypertension increases perioperative morbidity and mortality, intraoperative management should focus on prevention of potential triggers. In our patient, RA has the benefit of allowing spontaneous breathing and avoids the elevated pulmonary pressure that comes with mechanical ventilation. With GA, the initial administration of volatile anesthetics and mechanical ventilation can significantly decrease mean arterial blood pressure and coronary perfusion that impact right-ventricular contractility.13 Our anesthetic approach therefore helps preserve the patient’s cardiac reserve. Furthermore, RA may not only offer lower rates of postoperative cardiovascular and pulmonary complications, but also fewer deep surgical site infections and shorter hospital stays.14

However, RA is not without limitations. Potential risks include unpredictable block failure or patient decompensation that eventually requires conversion to GA.15 The ASA recommends awake intubation as a strategy for difficult airways, which was successful in our patient’s previous surgery and on standby in our case.4 However, this approach can also present with its own challenges. One study found that patients intubated awake had a first-pass success of 49% and higher rates of cardiovascular destabilization compared to those intubated under GA.3 Ultimately, the optimal choice of technique is not straightforward. The decision should be guided by the provider’s experience, patient comorbidities, surgical context, and all phases of the perioperative course—while always including a backup plan for securing the airway. Future studies comparing anesthetic outcomes of patients with similar anatomical features and physiological risk profiles could provide insights into advanced clinical decision-making.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with multiple high-risk features that made this a challenging case. By opting for spinal anesthesia, we were able to prevent potential airway obstruction and cardiopulmonary stress while maintaining adequate analgesic coverage. Although RA is not necessarily superior to GA for all patients with difficult airways, this case highlights the importance of individualized patient planning that anticipates complications from both anatomical and physiological perspectives. Further research is needed to compare the clinical and economic outcomes of these anesthetic approaches in managing difficult airways in healthcare practice.

Acknowledgments

none

Correspondence:

Blaze Borowski, 4802823049, blazeborowski@creighton.edu

Author Contributions

KH – writing, research

KG – writing, research

KB – writing, research

SD – writing, research

FS – writing, research

SK – writing, editing

OV – editing

BB – writing, editing

NS – writing, research

KL – writing, research

Disclosures and Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this case report have no disclosures and hold no conflicts of interest.