INTRODUCTION

Periprosthetic fractures (PSF) after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are defined as fractures occurring in the femur, tibia, and patella and within 15 cm of the joint line or 5 cm of the intramedullary stem.1

Periprosthetic fractures after TKA occurs in 0.3- 2.5% of patients after primary TKA and in 1.6-38% of patients following revision TKA.2,3

PSF after TKA incidence is rising over time due to the increase in the average age of the population and the increasing functional demands of the elderly population which lead on the one hand to a greater number of first implants and on the other to a greater risk of fracture.4,5

The treatment of this type of fracture should restore alignment, promoting bone union and allowing knee ROM to recover. The treatment options include conservative treatment, such as closed reduction and cast immobilization, and surgery, such as open reduction and internal fixation, plating, intramedullary nailing, revision TKA using a longer stem, external fixation, and arthrodesis with bone graft.3,4,6,7

Several biomechanical studies have compared fixation techniques of supracondylar femur fractures proximal to the TKA and the retrograde intramedullary nailing (RIMN) may provide greater stability in patients with a posterior cruciate ligament retaining femoral TKA component.8–10

This technique can be applied to patients with PSF after TKA only when there is no femoral component loosening, the intercondylar notch is properly open and comminution of the distal femur is sufficiently minor to allow the stable insertion of at least 2 distal interlocking screws.2 For these reasons, the study population sizes are usually small. Long-term knee function in elderly patients undergoing RIMN after TKA has rarely been assessed. The aim of this study is to evaluate the clinical and radiographical outcomes of RIMN for the treatment of PSF after TKA in a very old population with a minimum follow-up of two years after surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixteen patients with periprosthetic supracondylar fractures after total knee arthroplasty were treated with retrograde intramedullary nailing between January 2014 and December 2018.

Each had undergone TKA with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis. The implants employed were Genesis II Cruciate Retaining (CR) (Smith&Nephew, Memphis, TN, USA) in 7 knees and Vanguard CR (Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA) in 6 knees. The cause of the periprosthetic fracture was a low-energy trauma in all cases. No one patient had a history of painful total knee arthroplasty. CT scan was also performed to rule out femoral component loosening.

All fractures were classified as Type II according to the Rorabeck and Taylor classification system.11 This classification includes: Type I, a non-displaced fracture and the prosthesis is intact; Type II, a displaced fracture and the prosthesis is intact; and Type III, a non-displaced or displaced fracture, but the prosthesis is loose or failing. All interventions were performed using Trigen Meta-Nail Retrograde Femoral Nail (Smith & Nephew) by an expert surgeon with more than 5 years of experience. The patients were placed in the supine position on a radiolucent operating table, with about 45° knee flexion without skeletal traction. Through the scar from previous surgery, the medial parapatellar approach was used to expose the intercondylar notch of the femoral component. The alignment of the fracture was examined in both sagittal and coronal planes. A guidewire was placed using c-arm fluoroscopy and the medullary cavity was reamed. In five patients a minimally invasive open reduction and two metal cerclage fixation was required, because of non-acceptable closed reduction.

A Continuous passive motion machine was started from the 1st postoperative day. Weight-bearing was allowed at approximately 4-6th postoperative week. A postoperative assessment was performed on an outpatient basis at the 4th, 8th, 12th, and 24th postoperative week and then once a year thereafter. All patients were followed up until healing of the fracture or treatment failure occurred.

The clinical union was confirmed by pain-free weight-bearing as suggested by Han et al.12 Radiological union was defined as the presence of the trabecular or cortical bone across the fracture site and the presence of bridging callus on at least 3 radiographic views. At final follow up clinical outcomes were evaluated using Knee Society Score (KSS),13 and the Short form health survey (SF-12) questionnaire,14 to evaluated generic status health. KSS includes six items: pain, joint motion, flexion contracture, extension lag, alignment, instability, with a total score ranging from 0-100 in order of decreasing functional. SF-12 Questionnaire, comprising 12 questions that measure the physical, social, and mental components of patients.

The radiographic outcome, union, and, alignment, were evaluated directly on the X-rays.

Femoral alignment (in sagittal and coronal planes) was measured on simple radiographs. Post-operative complications were registered and then classified as, infections (superficial or deep) non-union, and re-fracture.

RESULTS

At the time of the final follow-up examination, which occurred after a mean interval of 48.3 months after surgery (range, 24 - 73 months), we evaluated 13 patients (11 female and 2 male). 3 patients were dead. The population study means age was 84 years (range, 77-89 years). The mean interval from TKA to the development of a fracture was 47.8 months (range, 13 - 156 months).

The baseline characteristic of patients who completed the follow-up is summarized in Table 1.

The mean operation time was 96 minutes (range, 40 - 140 minutes).

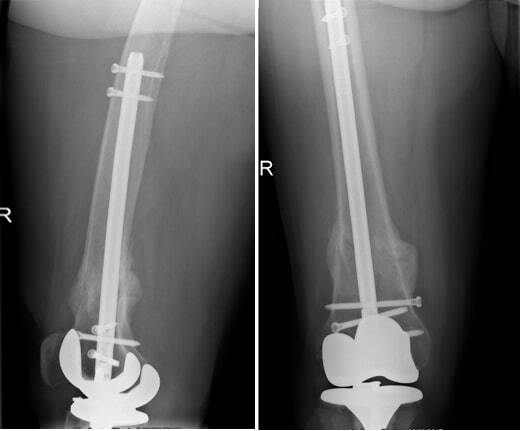

In all cases, the clinical and radiographic union was reached, and the radiographic union was observed after an average of 14.8 weeks (range, 12 - 40 weeks) postoperatively (Figure 1).

The mean KSS was 67.8 (range 52–86). According to the grading KSS up, there were 2 excellent, 3 good, 4 fair, and 4 poor results (Figures 2, 3). The mean active and passive range of motion (ROM) was 90.7° (range, 60° to 110°) and 98.6° (range, 80° to 115°), respectively.

For what concerns the SF-12, the mean Mental Component Score (MCS-12) was 42.31 (range 21.10- 52.72) and the mean Physical Component Score (PCS-12) was 37.11 (range 19.33- 46.01). These results were compared to the reference data for healthy subjects. Scores were similar to normative values for subjects in the comparable age group (MCS= 45.9 ± 12; PCS= 37.8 ± 11).14

One superficial wound infection was treated with two-weeks broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. In one patient an external sciatic popliteal nerve deficit was observed. After one year this deficit was completely recovered. Component loosening did not occur, and no revision was required in any case.

At the last follow up the coronal alignment averaged 0.3° valgus (range, 2.3° varus to 3.2° valgus) and the mean sagittal alignment was 1.2° of procurvatum (range, 0.7° of recurvatum to 3.4° of procurvatum).

DISCUSSION

PSF is the most common periprosthetic fracture with an incidence rate of 0.3–2.5%3 and one of the most important risk factors is advanced age, which is intrinsically related to osteoporosis and recurrent falls.15

Other risk factors are the chronic use of steroid therapy, inflammatory arthropathy such as rheumatoid arthritis, and patients suffering from neurological diseases.16,17

The most widely used classification system is the one proposed by Rorabeck and Tylor,11 which considers both fracture displacement and prosthesis condition.18,19

Treatment of periprosthetic fractures should aim to achieve a painless and stable knee with the proper restoration of alignment and ROM.

According to the Rorabeck and Tylor treatment algorithm,11 the non-displaced, stable fractures with well-fixed implants can be treated conservatively, while displaced fractures with stable components should be treated with internal fixation. The unstable prosthesis has to be treated with revision of previous prosthesis, with or without bone grafting.

Ebraheim at al.20 reported that the most frequent type of periprosthetic distal femur fracture after total knee arthroplasty was Rorabeck type II. The most common treatments for these types of fractures are locked plating and intramedullary nailing, with similar healing rates of 87% and 84%, respectively. Fractures treated with a locking plate had a complication rate of 35% (including non/mal/delayed union and the need for revision) while fractures treated with an intramedullary nail had a complication rate of 53%. Also, Shah et al.21 detected equivalent union rates between the intramedullary nail and locked plate fixation for distal femur periprosthetic fractures.

Others authors22–25 showed that RIMN may be prone to higher rates of malunion compared to minimally invasive plating, but no statistically significant difference was found postoperatively in terms of rates of other complications.

The results of a recent meta-analysis26 did not support the theoretical clinical advantage of RIMN compared with LCP. There were no differences in any of the parameters tested such as clinical outcomes, nonunion rates, and revision rates. However pooled data showed that mean operation time was 10.89 min shorter with RIMN than LCP, and mean KSS was 1.11 points higher with RIMN than LCP, but these differences were not statistically significant.

If considering plating the less invasive stabilization system with cerclage wiring and the use of a polyaxial locking plate is the preferable technique today with regard to soft tissue preservation, but requires an experienced surgeon and is more difficult to perform in complex fractures.27,28

Biomechanical studies have shown that for PSF after TKA, RIMN can guarantee greater stability in patients with a posterior cruciate ligament retaining femoral TKA component8 and this technique may improve the rate of the union while decreasing soft-tissue trauma.1

Makinen et al.10 compared biomechanical results of locking plates and retrograde intramedullary nails in periprosthetic supracondylar fractures of the distal femur. In this study, RIMN has biomechanical advantages over LCP in resisting external loads because RIMN includes coaxial implantation with the anatomical axis of the femur and is the stiffest construct under axial loading.

The mean KSS in our patients was 67.8 (range 52-86), which is lower than the score reported by Lee et al29 with a mean KSS of 81.5 (range 50-100), but in the youngest age group (71 years). The literature lacks of long-term knee function studies in elderly populations.

According to the KSS at the last follow up we had nine patients with satisfactory results. Four patients of our series obtained a poor clinical outcome: 3 of them suffered of a proximal femur fracture (2 ipsilateral and 1 controlateral) and consequent surgery during the follow-up period. This fact underlines the intrinsic fragility of the elderly patient and the difficulty to have a homogeneous ratio stiffness/elasticity and uniform stress distribution while treating a bone segment with means of synthesis. Furthermore, the final score could be influenced by the patient’s comorbidities.

Gliatis et al.30 and Han et al.12 observed that RIMN can lead all PSF after TKA to union within 3 months and radiographic bone union can be observed in average after 14 weeks from the intervention with a mean ROM of the knee >90° after 3 years.

Although we considered a very old population with a long follow up period (if considering the mean age of 84 years) our data confirm the efficacy of RIMN for treating PSF after TKA both for clinical and radiological data. In all cases clinical and radiographic union was reached, and radiographic union was observed after an average of 14,8 weeks postoperatively. Our cases had a knee mean active flexion than 90° and presented acceptable functional outcomes at the final follow-up.

Furthermore, in this study, the SF-12 was used as a general measure of health. To the best of our knowledge, no authors previously used the SF-12 to evaluate the quality of life in RIMN. In particular, our scores did not significantly differ from that of age-matched, healthy subjects.

Our data also confirm the safety of treating PSF after TKA in an elderly population. The two complications observed were solved: the superficial wound infection was treated with two-weeks of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and the external sciatic popliteal nerve deficit was completely recovered after one year of follow-up. Component loosening did not occur, and no revision was required in any case.

However, our study has 2 main limitations. First, it suffers from a lack of randomization of patients and controls because of the retrospective nature of these controls. The second shortcoming is the small number of patients enrolled.

Despite these limitations, we valued several data and a validated instrument (SF-12) was used to evaluate generic status health in patients treated with retrograde intramedullary nails in periprosthetic supracondylar fractures of the distal femur.

CONCLUSION

Although our retrospective long-term evaluation confirms the efficacy and safety of RIMN for PSF treatment in the elderly population, further prospective studies, with a larger population, are required to better understand the best way of treating this emerging pathology in an increasingly elderly population.

Contributions

SSF study conceiving, data collection, manuscript writing - original draft;

DC, MB, GL and GO data acquisition;

RP, APG assisted with the data interpretation;

SC methodology, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revising.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Funding

None

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

**_a_80-year-old_woman_sustained_right_periprosthetic_supracondylar_fracture_(psf)_af.jpeg)

**_a_80-year-old_woman_sustained_right_periprosthetic_supracondylar_fracture_(psf)_af.jpeg)