Introduction

Bone metastasis is a prevalent and serious complication in primary malignancies, especially those originating from the prostate, lung, kidney, breast, or thyroid. It is estimated that up to 85% of patients who die from breast, prostate, or lung cancer have bone metastases at the time of death.1,2 These metastases can lead to significant complications, including pain, fractures, limited mobility, and decreased independence, severely impacting quality of life. Persistent pain associated with bone metastasis can also contribute to mental health issues such as depression and anxiety.1

The incidence of bone metastases in cancer patients exceeds 60%, particularly in those with solid tumors such as breast, prostate, and lung cancers.2,3 Bone lesions may lead to severe complications such as fractures, spinal compression, malignant hypercalcemia, and chronic pain that is resistant to medical therapy.4 Treatment for bone metastases is primarily palliative and involves localized therapies such as interventional analgesia, radiation therapy (RT), and surgery, as well as systemic treatments such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy, radiopharmaceuticals, and bisphosphonates. Pain relief often necessitates the use of opioids and anti-inflammatory drugs.1 Managing pain in patients with metastatic cancer is a complex clinical issue that frequently requires a multidisciplinary approach, including oncologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, pain management specialists, and radiation oncologists.5

In recent years, minimally invasive interventional oncology techniques such as percutaneous imaging-guided cryoablation (CA) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) have emerged as promising treatment options for metastatic bone disease.5 These techniques provide localized tumor control and effective pain management for patients with bone metastases who are either unresponsive to or ineligible for conventional therapies.6

Radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation are among the most frequently utilized and studied ablative methods, demonstrating similar effective clinical outcomes in both palliative and curative contexts.7 RFA relies on high-frequency alternating electrical currents to generate heat, causing coagulative necrosis and tumor destruction.6 In contrast, cryoablation utilizes extreme cold to induce tumor cell death through ice formation, necrosis, apoptosis, and vascular stasis.8 Both techniques have been shown to provide substantial pain relief, improve mobility, and enhance quality of life in patients with bone metastases.4,8

The purpose of this review is to evaluate and summarize evidence on the effectiveness, safety profiles, and clinical outcomes of cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation for painful bone metastases. Where data permitted, we performed separate single-arm meta-analyses for each modality and narratively summarized findings from the limited number of studies that directly compared the two techniques.

Methods

1. Literature Search Strategy

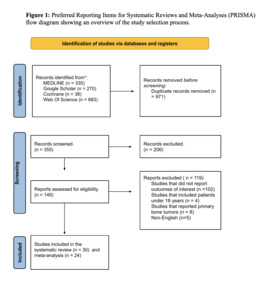

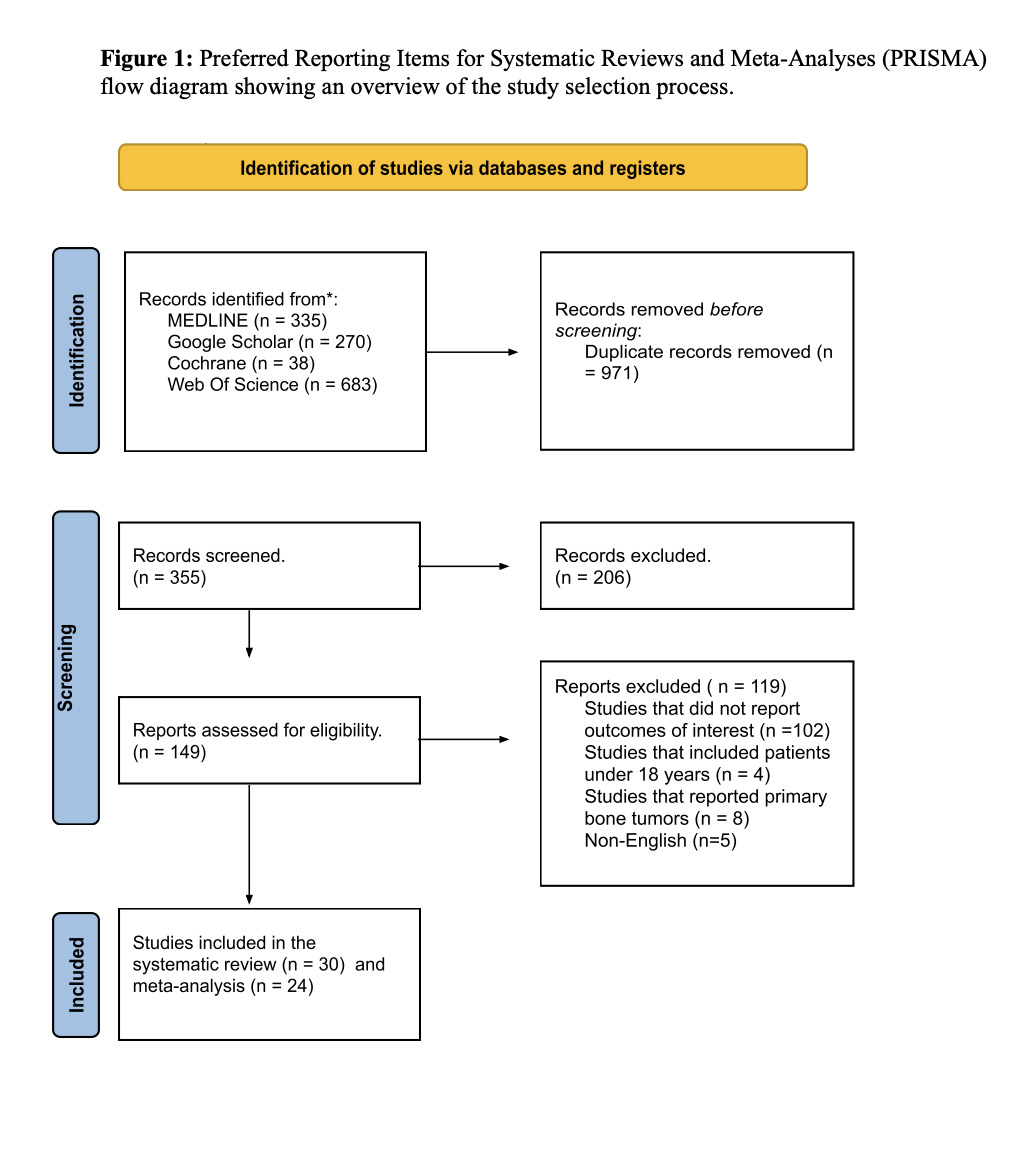

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.9 The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (Registration No. CRD42024573550).

A comprehensive electronic search was conducted in Ovid MEDLINE, Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Google Scholar. Additionally, ClinicalTrials.gov was searched for relevant ongoing or unpublished trials. The reference lists of all included studies and related systematic reviews were manually screened to identify any additional eligible studies. The search covered literature published between January 2000 and June 2025.

The search strategy was independently developed by two reviewers (A.A. and Y.M.) using the PICOS framework10 and approved by the full review team. Although a consistent set of core concepts was used, targeting radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation, and bone metastases, each database employed a tailored version of the strategy to account for differences in indexing systems, controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH), and syntax requirements.

The full, reproducible search strategies for each database, including applied filters (e.g., date range, language, human studies), are provided in Supplementary files.

2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This review included studies published in English between January 2000 and January 2025 that examined adult patients (≥18 years old) with bone metastases treated with either RFA alone, CA alone, or a direct comparison between the two techniques. Eligible studies were required to report outcomes relevant to the clinical question. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and retrospective prospective cohort studies, single arm studies were included. Studies were excluded if they were published outside the specified date range, focused on paediatric patients (<18 years old), reported primary bone tumors rather than metastatic lesions, or did not involve RFA or CA as a treatment modality. Additionally, case reports, abstracts, conference proceedings, editorials, animal studies, and narrative reviews were excluded. Studies published in languages other than English, as well as duplicate studies identified during screening, were removed from the review.

3. Selection of Articles and Data Extraction

For deduplication, all the records that came from the primary search were imported into EndNote 20 (CA, USA). Rayyan (MA, USA) was then used to screen the duplicated results. Based on abstracts and titles, four authors (M.A., M.A., F.A., and S.A.) . At each stage of screening, at least two authors independently evaluated the publications for relevance. The same reviewers then independently assessed the full texts of retained studies to determine eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus, and if unresolved, a fifth reviewer (Alaqeel) was consulted .Data extracted from the included studies covered several domains. Study characteristics included first author, year of publication, study design, and reported time points for outcome assessment. Patient and intervention characteristics included sample size, mean age, sex, primary tumor site, metastatic site, tumor size, tumor composition, type of ablation intervention, and whether both interventions were applied. The predefined primary outcome was pain relief after intervention. Secondary outcomes were adverse events following ablation, as well as tumor progression and recurrence.

4. Risk of bias

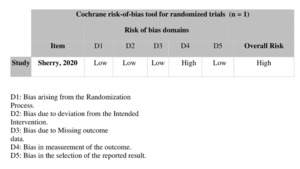

The bias risk of the included nonrandomized studies was assessed using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool, which evaluates seven domains of bias: confounding, selection of participants, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of the reported result. Two independent reviewers (M.A. and M.A.) assessed each study, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer (Alnajres). Based on ROBINS-I guidance, studies were categorized as having low, moderate, or serious.11 For randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias 2 (RoB 2) tool was used to evaluate bias across five key domains: bias from the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and selection of reported results.12 The risk of bias was independently assessed by the two previously mentioned reviewers, and any discrepancies were resolved in consultation with the third reviewer. The overall risk of bias for each study was classified as low, high, or unclear based on the assessment of these domains.

5. Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.4 software (RevMan). Separate single-arm meta-analyses were conducted for the RFA and CA cohorts using the standardized mean difference (SMD) from baseline as the summary effect measure.

A pooled head-to-head meta-analysis was not performed because the number of direct comparative studies was small (n = 5), and substantial heterogeneity in study designs, baseline characteristics, and outcome measures precluded a credible statistical comparison.

As a result, these comparative studies were excluded from the quantitative synthesis and were instead analyzed using a narrative synthesis approach to qualitatively contextualize the results of the single-arm analyses.

The standardized mean difference (SMD) accounts for differences in scale and variance and was used to aggregate within-group changes in pain intensity across heterogeneous single-arm studies. The calculations of the SMD and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were based on the available means and standard deviations at each follow-up interval.

Meta-analyses were performed at five predefined timepoints: 24 hours, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months posttreatment. The results were synthesized and visualized via forest plots, which illustrated the effect sizes of individual studies alongside the overall pooled estimate derived from a random-effects model, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The plots also indicate the relative weight assigned to each study and report the overall p-value to assess the statistical significance of the pooled effect. Heterogeneity was quantified via the I² statistic, with values exceeding 75% interpreted as indicative of substantial heterogeneity. Additionally, Tau² was reported to estimate the between-study variance in absolute terms, whereas the chi-square (χ²) test was employed to evaluate whether the observed differences in effect sizes across subgroups were statistically significant. Funnel plots were used to assess the potential for publication bias by visually identifying asymmetry suggestive of selective reporting.

Results

1. Literature search results

Among the 1,326 studies identified across the four databases, after duplicate removal, 986 titles and abstracts were screened. Of these, 837 articles were excluded based on eligibility criteria. The remaining 149 articles underwent full-text screening, resulting in the exclusion of 119 studies. Ultimately, 30 studies were included, all of which were part of the qualitative synthesis (systematic review), while 25 of them were included in the quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis). The study selection process is detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

2. Study characteristics and risk of bias

Among the 30 included studies, five were comparative cohort studies evaluating radiofrequency ablation (RFA) versus cryoablation (CA) for pain palliation in patients with bone metastases. Twelve studies assessed RFA alone, and thirteen focused only on CA. The studies were published between 2000 and 2025 and collectively included 1,121 patients. Geographically, the distribution of studies was as follows: twelve were conducted in the United States, six in Italy, four in France, four in China, and one each in Germany, Egypt, Switzerland, and Japan. In terms of study design, 17 were retrospective, 12 were prospective, and one was a randomized controlled trial (Table 1). Risk of bias was assessed using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for nonrandomized studies11 and the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials.12 The overall risk of bias varied across studies, with some rated as having low, moderate, or serious risk of bias (Table 2). The randomized controlled trial was assessed to have an overall high risk of bias (Table 3).

3. Narrative synthesis of comparative cohort studies

3.1. Study characteristics

Five comparative cohort studies reported direct comparisons between RFA and CA; because of small numbers, variable baseline characteristics, and methodological heterogeneity, these studies are synthesized narratively below rather than pooled quantitatively. These studies included both prospective37 and retrospective5,7,38,39 designs, all of which utilized percutaneous ablation techniques under CT or fluoroscopic guidance. The patient populations were heterogeneous with respect to sex and primary tumor origin, which most included breast, prostate, renal, and lung cancers. The treated lesion sites varied and included the spine, pelvis, sacrum, and long bones. Ablation was performed via either monopolar or bipolar energy systems at standard temperature thresholds. In several studies, cement augmentation was additionally employed to provide structural stabilization (Table 4).

3.2. Pain Outcomes

Two comparative cohort studies, Masala et al.37 and Thacker et al.,5 provided directly comparable outcome data across multiple timepoints. At baseline, pain scores were similar between the treatment groups, suggesting comparability of initial clinical status. Early follow-up at 24 hours and 1 week revealed greater absolute pain reduction in CA-treated patients, with Masala et al.37 reporting a steeper decline in pain scores at 24 hours and Thacker et al.5 suggesting potentially greater pain relief with CA at 1 week (VAS 3.5 ± 2.91 vs 5.0 ± 2.04). However, this early advantage diminished by 1 month, where pain relief was comparable between the groups (Masala: 2.7 ± 0.8 for RFA vs 2.7 ± 0.9 for CA) and was sustained through 3 and 6 months, with minimal intergroup differences.

While both studies offer consistent narrative evidence suggesting faster initial relief with CA, the small number of studies, concerns over baseline imbalance, instrumentation heterogeneity, and differing pain subscales precluded formal meta-analysis and definitive conclusions. These data were therefore integrated narratively and included as supportive context for the single-arm meta-analysis that forms the core quantitative synthesis.

3.3. Tumor Control and Safety

Tumor control outcomes were inconsistently reported across the included studies. Among RFA studies, Gevargez et al.15 reported a mean time to progression of 730 ± 54 days, with 28 of 33 treated lesions showing no evidence of progression, suggesting the potential for local disease stabilization in select cases. Cazzato et al.38 noted that 43% of lesions treated with curative-intent RFA progressed, whereas 0% of those treated palliatively progressed, highlighting the influence of treatment intent on oncologic outcomes. However, many studies do not provide imaging-confirmed local control data or standard follow-up intervals, limiting comparative interpretation.

Cryoablation studies offered slightly more consistent oncologic follow-up. Yang et al.31 and Arrigoni et al.30 reported stable disease in most patients at 3–6 months, but without formal progression analysis. Gallusser et al.1 reported good early local control, although data beyond 6 months were sparse.

In terms of safety, both ablation modalities demonstrated a favorable profile. Transient adverse events are common but generally self-limiting. Among RFA-treated patients, complications include mild radiculopathy,37 minor contralateral limb numbness,15 and, rarely, second-degree burns.23,24 BelfioreG et al.22 reported no major events.

Similarly, cryoablation-related complications are rare. The most frequently observed symptoms were mild postprocedural pain or nerve irritation, as reported by Tomasian et al.35 and Wallace et al.34 Only one case of osteomyelitis was reported by Callstrom et al.,27 and no serious permanent neurological deficits were documented.

Overall, both modalities appear safe and well tolerated, with transient side effects that are resolved without long-term impact. The reporting of adverse events and local control remains inconsistent, underscoring the need for future standardized outcome definitions and follow-up intervals (Table 5).

4. Single-Arm Analysis for Radiofrequency Ablation

4.1. Study characteristics

Twelve studies have assessed the efficacy of RFA for pain palliation in patients with bone metastases. Among these, five were retrospective,13–17 six were prospective,18,19,21–24 and one was a randomized controlled trial.20 Patient populations varied in terms of sex and primary tumor type. Most lesions were treated in the spine, particularly the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. A range of pain assessment tools have been utilized across studies, including the visual analog scale (VAS), brief pain inventory functional subscale (BPI-FS), and numeric rating scale (NRS/NPRS). The baseline pain scores were consistently high, typically between 7.5 and 8.5, highlighting the substantial pain burden experienced by patients prior to RFA treatment. Following intervention, a progressive and substantial decline in pain was observed at all subsequent time points (Table 6).

4.2. Quantitative Synthesis of Pain Outcomes

Masala et al.37 reported a rapid decrease from 8.6 ± 1.23 at baseline to 2.7 ± 0.8 in one month and 1.9 ± 0.8 in six months. Zhao et al.17 also demonstrated consistent reductions: the baseline VAS score of 8.5 ± 1.5 decreased to 4.7 ± 1.1 at one week, 5.1 ± 1.2 at one month, and further declined to 4.3 ± 1.3 and 3.9 ± 1.2 at 3 and 6 months, respectively. Earlier studies, such as those of Goetz et al.23 and Matthew R.,24 reported similar trends in worst pain (WP) and average pain (AP) scores, with marked improvement maintained over time. The incorporation of new studies added greater resolution across all time intervals. Greenwood et al.13 and Zheng et al.17 reported robust early pain reduction data, with the former reporting a reduction from 8.0 ± 2.3 to 4.3 ± 3.1 at 24 h and to 2.9 ± 3.3 at 1 month. Similarly, Sayed et al.18 reported that pain improved from 5.9 ± 2.5 to 2.6 ± 2.0 at 1 month. Safety profiles remained favorable. Gevargez et al.15 reported mild contralateral limb numbness, whereas Goetz et al.23 and Matthew R. et al.24 reported isolated second-degree burns. No serious complications were reported in most of the newer studies, confirming the procedure’s minimal risk.

A meta-analysis of standardized within-group changes from baseline was conducted for studies reporting pain scores at 24 hours, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months postintervention (Figure 2A). At 24 hours, the pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) was –1.14 (95% CI –1.98–0.30) based on five studies, with high heterogeneity (I² = 84.5%, τ² = 0.9369). By 1 week, the effect size increased (SMD = –1.91; 95% CI –2.59 to –1.23), reflecting a sharper early decline in pain. This effect continued at 1 month, with a pooled SMD of –2.41 (95% CI –3.07 to –1.76) across 12 studies, and at 3 months, with an SMD of –3.17 (95% CI –3.99 to –2.35) across 10 studies. The greatest magnitude of pain relief was observed at 6 months, where the pooled effect size was –3.50 (95% CI –4.72 to –2.27), on the basis of six studies. Heterogeneity remained consistently high across all timepoints (I² > 85%), although the direction and magnitude of effects were broadly consistent. Tests for subgroup differences by lesion site showed no statistically significant effect modification at 1 week (p = 0.44), 1 month (p = 0.12), or 3 months (p = 0.93).

The overall random-effects model across all studies demonstrated a large pooled effect (SMD = –2.48; 95% CI –2.87 to –2.08), with a wide prediction interval (–5.37 to 0.42), indicating substantial between-study variability but robust evidence of treatment benefit (Figure 1A). These findings provide compelling support for the analgesic effect of RFA, particularly in the medium-term period following intervention.

Figure 2B presents the funnel plot used to assess publication bias across the included RFA studies. Visual inspection suggests mild asymmetry, with a slight leftward skew toward smaller studies reporting stronger effects. However, the overall distribution remained broadly symmetrical, with larger studies clustering around the mean estimate, indicating no substantial evidence of small-study effects.

5. Single-Arm Analysis for Cryoablation

5.1. Study characteristics

Thirteen studies investigated the use of CA for pain relief in patients with bone metastases. Of these, five were prospective studies,25–29 whereas the remaining eight were retrospective.1,7,30,31,33–36 Cryoablation has shown consistent analgesic benefits across studies, with most patients presenting with moderate to severe baseline pain and reporting significant pain reduction following treatment. The pain assessment methods used included the VAS, BPI-FS, and NRS, with several studies differentiating between pain experienced during weight-bearing activities and that experienced at rest.

5.2. Quantitative Synthesis of Pain Outcomes

Yang et al.31 reported a decrease in the VAS score from 7.1 ± 1.1 to 1.8 ± 1.3 at 6 months. Masala et al.37 reported that pain decreased from 7.9 ± 1.0 to 2.6 ± 1.5 at one week, 2.7 ± 0.9 at one month, and 2.1 ± 0.8 at 6 months. Wallace et al.34 provided multi time point data with 8.0 ± 1.9 at baseline, which decreased to 6.0 ± 2.0 at 24 h, 4.0 ± 1.5 at 1 w, 2.0 ± 1.0 at 1 m, and 0.5 ± 0.3 at 6 m. Tomasian et al.35 and Motta et al.33 reported pain reduction of 5–7 points across similar timelines. Most studies reported minimal or no complications. Hegg et al.36 and McArthur et al.32 noted transient pain flare-ups or minor nerve irritation, with no serious adverse events.

For CA, the SMD at 24 hours was –2.43 (95% CI –3.84----1.02) on the basis of five studies, with considerable heterogeneity (I² = 92.3%, τ² = 2.3187). The pooled estimate at 1 week was –1.16 (95% CI –2.04 to –0.28), whereas at 1 month, the pooled SMD was –2.05 (95% CI –3.22 to –0.87), both reflecting robust pain reduction with high between-study variability (I² > 86%) (Figure 3A).

Sustained and substantial effects were also observed at later follow-ups. At 3 months, the pooled SMD was –2.55 (95% CI –3.46 to –1.65) across 11 studies (I² = 88.5%, τ² = 2.5080), whereas at 6 months, pain reduction remained large (SMD = –2.14; 95% CI –3.43 to –0.85), with heterogeneity reaching I² = 92.7%.

The overall random-effects pooled estimate revealed a strong analgesic effect (SMD = –2.08; 95% CI –2.57 to –1.60), and the prediction interval (–5.29 to 1.12) suggested that, despite variability, most individual settings still demonstrated benefit (Figure 2A). These findings indicate that CA consistently reduces pain intensity across a range of follow-up durations and study populations. These findings support the conclusion that CA produces significant and sustained improvements in pain scores over time, although the effect sizes were generally smaller than those observed with RFA.

Figure 3B shows the funnel plot of effect sizes for CA studies. While the plot was broadly symmetrical, some left-sided skew was observed, particularly among smaller studies reporting stronger treatment effects. Larger studies clustered near the pooled mean, indicating a limited risk of small-study bias and a reasonable overall distribution.

Discussion

Bone metastasis is the most common form of metastatic disease, affecting about two out of every three cancer patients.40 In the U.S, approximately 350,000 individuals die annually with bone metastases.41 The most frequent primary tumors associated with skeletal spread are breast, prostate, and lung cancers41,42 Spinal vertebrae are most commonly affected, particularly the mid-thoracic region (T4–T7).43

Pain is the most frequent and debilitating symptom, often leading to reduced mobility and diminished quality of life.44,45 Traditional management includes EBRT, chemotherapy, surgery, hormonal agents, bisphosphonates, and newer immunotherapies46 Despite this, a significant proportion of patients experience suboptimal pain relief or relapse after initial response.47,48

Minimally invasive, image-guided interventions have emerged as alternatives for patients unsuitable for conventional treatments. These include radiofrequency ablation (RFA), cryoablation (CA), microwave ablation (MWA), and magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS), offering targeted therapy for painful skeletal metastases.22,23,25

This study compares the effectiveness of RFA and CA in treating bone metastasis, focusing on pain relief, local tumor control, and complication profiles.

RFA is typically used for smaller osteolytic lesions due to better conductivity. It is fast but less effective in sclerotic tumors and often requires deep sedation. CA, in contrast, is suited for larger sclerotic lesions, is less affected by bone density, allows real-time ice ball visualization, and is generally better tolerated due to its anesthetic properties.49

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that compare cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of painful bone metastases. While previous literature has evaluated each modality individually, no prior work has synthesized and analyzed outcomes between the two techniques in a unified, head-to-head framework. This comparison is critical for clinicians choosing between thermal ablation options for palliative care, especially when balancing pain relief, safety, and tumor control.

Existing systematic reviews have addressed RFA in isolation, focusing on its efficacy in pain reduction and functional outcomes, but without exploring other ablation modalities (Murali et al., 2021).6 Cryoablation has also been studied in meta-analyses, with results showing significant and durable pain relief across various time points (Torabi et al., 2025) [[8], as well as favorable safety outcomes and procedural considerations in spinal applications (Fallahi et al., 2025) [[50]. One broader review included multiple ablation methods (RFA, CA, MWA, MRgFUS), but analyzed each separately without comparing their outcomes.4 By bringing both cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation into direct comparison, our study fills a notable gap in the current evidence base and provides a more practical, evidence informed foundation for clinical decision making.

EBRT versus Thermal Ablation

In a retrospective study by Di Staso et al. (2015), patients with single painful bone metastases were treated with either EBRT alone, CA alone, or a combination of CA followed by EBRT. The results showed that patients who received CA—especially in combination with EBRT—achieved substantially better pain relief by 12 weeks compared to those treated with EBRT alone.50

Although studies directly comparing EBRT and RFA are limited, the available evidence suggests that combining RFA with EBRT offers superior pain outcomes compared with EBRT alone. In a separate retrospective analysis by Di Staso et al. (2010), a complete pain response at 12 weeks was observed in 53.3% (8/15) of patients treated with the combined RFA and EBRT protocol, compared with only 16.6% (5/30) in the EBRT-only group. Furthermore, the overall pain response rate was significantly greater in the combined therapy group (93.3%) than in the EBRT-alone group.51

These findings highlight the potential additive benefit of incorporating ablative therapies with conventional radiotherapy for enhanced pain control in patients with bone metastasis.

Effect of Thermal Ablation on Short-Term Pain

Two comparative studies have assessed pain outcomes within 24 hours post-procedure,5,37 alongside three studies evaluating RFA,17,22,23 and three evaluating CA.31,33,34 Collectively, the data demonstrate that CA yields a significantly greater immediate reduction in pain at 24 hours compared to RFA. While both analyses indicate a strong treatment effect, cryoablation appears to provide a more rapid onset of analgesia.

This early superiority is likely due to cryoablation’s distinct mechanism of action. The freezing temperatures disrupt local nerve conduction, which not only blunts nociceptive signaling during the procedure but also reduces post-ablation pain more effectively than the thermal injury produced by RFA [[53,54].

Similarly, a recent meta-analysis by Fallahi et al. focused on spinal metastasis ablations demonstrated a notable and rapid reduction in pain scores by the first day following cryoablation. This early pain relief was attributed to cryoablation’s ability to directly affect periosteal and osseous nerve fibers through localized freezing, leading to the disruption of nociceptive pathways shortly after treatment [[50]. In a comparative study by Thacker et al., patients treated with CA required significantly less opioid analgesia within the 24-hour periprocedural period. Specifically, CA was associated with a mean decrease of 24 morphine equivalent doses, whereas RFA was linked to a mean increase of 22 doses. Additionally, CA was associated with a shorter postprocedural hospital stay compared to RFA.5

These findings support the hypothesis that cryotherapy may provide more effective and better-tolerated immediate pain relief in patients with bone metastasis, although further high-quality comparative studies are needed to confirm these observations.

Effect of Thermal Ablation on Long-Term Pain

One comparative study assessed pain outcomes at 3 months post procedure,37 supported by nine additional studies evaluating RFA14,17–24 and ten evaluating CA.1,25,27–34 Collectively, the data suggests that RFA may provide superior long-term pain relief compared to CA at the 3-month period. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) achieves long-term pain relief by inducing coagulative necrosis of sensory nerves, which disrupts pain transmission and delays nerve regeneration.52 Additionally, RFA stimulates immune activation through the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as HSP70 and HMGB1, facilitating the clearance of damaged tissue and helping resolve inflammatory pain.53 Furthermore, RFA reduces tumor burden, eliminates cytokine-producing cells (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), inhibits osteoclast activity, and decreases local acidity, these changes promote structural stability and reduction in nociceptor sensitization.24

This trend was maintained at 6 months post-procedure. The same comparative study, in addition to five studies evaluating RFA14,17,21–23 and five evaluating CA,25,27,29,31,34 consistently demonstrated greater pain reduction in the RFA group. These findings point toward a possible long-term analgesic advantage of RFA over CA in the context of bone metastases. The sustained efficacy observed with RFA may reflect differences in thermal dynamics, lesion coverage, or post-ablation tissue response compared to cryoablation. However, notable heterogeneity was observed across studies, possibly due to differences in methodology, lesion type, pain assessment tools, or the generally high risk of bias in the available evidence. To address this, we performed a subgroup analysis stratified by lesion site, but this showed no statistically significant effect modification at 1 week (p = 0.44), 1 month (p = 0.12), or 3 months (p = 0.93). Moreover, only one study to date has directly compared RFA and CA in a head-to-head analysis, reporting a significant difference in long-term pain outcomes between the two modalities.37 This highlights a significant gap in the literature, as high-quality comparative data remains limited.

Technical Advances: Steerable RFA and Cementoplasty

Steerable bipolar RFA probes, combined with high-viscosity cementoplasty, are emerging as a safe and effective option for treating difficult-to-access extraspinal bone metastases. Their articulating tips allow broader ablation zones through a single access point, minimizing trauma in complex or load-bearing areas.

In a retrospective study by Pusceddu et al., this approach led to immediate pain relief, with VAS scores dropping to 0 in 53% of patients within one week, and improved mobility in 94% by one month. No major complications were reported.54 These findings align with Faiella

et al., who reported significant and sustained VAS reduction using traditional RFA with cementoplasty.55 Together, these results support the use of steerable RFA as a minimally invasive solution for effective tumor control and rapid functional recovery in anatomically challenging metastases.

Local Tumor Control

Out of 30 studies in our review, 12 reported on local tumor progression after ablative treatment for bone metastasis. In a comparative study by Zugaro et al., patients were evenly divided into RFA and CA groups. By 12 weeks, both modalities showed recurrence in a small portion of patients, with RFA showing slightly lower recurrence.

Five studies evaluated RFA outcomes13–17; two of them reported complete absence of recurrence within the first year of follow-up. Gevargez et al. demonstrated durable tumor control over an extended observation period, with the majority of patients maintaining local stability and only a few experiencing disease progression. These results suggest that RFA can offer sustained tumor control in selected cases, though outcomes may vary based on treatment intent—curative versus palliative.

Six studies assessed CA,1,30,32,34–36 with findings depending on patient selection and follow-up duration. For instance, McArthur et al. reported minimal progression in their patient cohort during the observed period, while Wallace et al. showed a relatively high rate of local tumor control one year after treatment, although some progression still occurred.

A systematic review by Murali et al. evaluating RFA in patients with bone metastases found recurrence to occur in a minority of cases, across varied follow-up durations ranging from months to several years.6

In comparison, a systematic review of CA in spinal metastasis demonstrated local control rates spanning a wide range from 60-100%, depending on follow-up methodology and clinical context [57]. Fallahi et al.'s meta-analysis also reported favorable 70% local tumor control outcomes for CA-treated patients over intermediate follow-up periods.56

Overall, these findings suggest that both RFA and CA are capable of achieving meaningful local tumor control. However, inconsistencies in patient populations, follow-up intervals, and outcome definitions emphasize the need for standardized, long-term comparative studies.

Complications

As demonstrated across the included studies, both RFA and CA are minimally invasive procedures performed under image guidance with either local anesthesia or conscious sedation, making them feasible and well tolerated even in patients with advanced disease. According to the studies included in this review, complications were generally mild and self-limiting. For RFA, reported adverse events include mild radiculopathy (Masala et al., 2011),37 minor contralateral limb numbness (Gevargez, 2007),15 and isolated second-degree burns (Goetz et al., 200423; Matthew R, 200224). Similarly, cryoablation was well tolerated, with studies such as Tomasian et al. (2018),35 Wallace et al. (2016),34 and McArthur et al. (2018)32 reporting only mild postprocedural pain or nerve irritation. Only one case of osteomyelitis has been reported (Callstrom et al., 2013),27 and no permanent neurological injuries were observed in either group, confirming the overall safety and low complication rates of both techniques (Zhao et al., 201817; Sayed et al., 202118). This favorable safety profile reinforces their suitability in oncology patients with limited treatment options, especially those in whom conventional surgery or systemic therapies may be contraindicated.

Role of Navigation Systems and Neuroprotection

Advanced navigation tools like SIRIO are becoming increasingly important in spinal tumor ablation, where protecting nearby nerves is critical. SIRIO offers real-time 3D guidance, helping clinicians place needles with greater precision while reducing both radiation exposure and procedure time. In one study, procedures using SIRIO had significantly lower radiation doses (307.4 vs. 460.3 mGycm) and were much quicker (13.5 vs. 32.3 minutes). This precision also improved neuroprotection and led to better pain control at three months. Both SIRIO and non-SIRIO techniques were safe, but the added accuracy and efficiency make navigation systems especially valuable for treating fragile patients and complex spinal lesions.57

Limitations and Future Directions

This review is limited by methodological heterogeneity, particularly in pain assessment tools, follow-up durations, and the use of adjunctive therapies such as cementoplasty, which confound the pain-relieving outcomes of RFA and CA. An additional limitation is that most pooled quantitative results were produced from separate single-arm meta-analyses of RFA and CA study sets rather than pooled head-to-head comparisons. Consequently, differences in pooled effect sizes between RFA and CA may reflect between-study differences (patient selection, baseline pain, adjunct therapies, outcome measurement, follow-up) rather than true modality superiority.

The lack of randomized controlled trials and direct comparative studies restricts the strength of conclusions regarding the relative efficacy of these modalities. Future studies should include standardized pain scores (e.g., VAS, NRS, and BPI) recorded at defined intervals (e.g., 24 hours, 1 month, and 3 months), as well as consistent reporting of tumor control and complication rates.

Expanding access to image-guided ablation should be a priority in palliative care, especially for patients ineligible for conventional treatments. This requires institutional investment in ablation technologies and the training of interventional radiologists to ensure appropriate and timely delivery of these minimally invasive therapies.

Conclusion

Bone metastasis remains a common and serious complication of primary malignancies and poses a major clinical challenge because of its high prevalence and significant impact on patient quality of life. While external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) continues to serve as the standard for pain palliation and local control, its efficacy is limited because patients report minimal relief and continue to experience pain. Minimally invasive, image-guided thermal ablation techniques—namely, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and cryoablation (CA), have emerged as promising conventional alternative therapies.

This study revealed that both radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and cryoablation (CA) significantly reduce pain in patients with bone metastases. On separate pooled analyses, cryoablation appeared to show larger early effect sizes, greater short-term pain reduction, less opioid use, and shorter hospital stays, while radiofrequency ablation tended to show larger medium-term effect sizes and more consistent long-term control. Because these pooled results come from different sets of studies, they should not be interpreted as evidence of superiority of one modality over the other.

Moreover, combining thermal ablation with EBRT results in greater pain reduction than either modality alone. However, the lack of randomized comparative trials limits definitive conclusions regarding the relative efficacy of these treatments. Future research should prioritize standardized pain assessment tools and long-term outcome studies to better inform clinical decision-making and improve patient care.

List of abbreviations

CA: Cryoblation

RFA: radiofrequency ablation

EBRT: External beam radiation therapy

MWA: Microwave Ablation

MRgFUS: magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound

RT: Radiation Therapy

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

All recorded data from the data extraction process of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Competing Interests

All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions

MA, AA: study conception and design; data acquisition, analysis and interpretation; and drafting of the manuscript. YM and MA: data acquisition, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. SA and FA: data acquisition and manuscript drafting. MA: drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

.png)

.png)